Keep up with our latest news and projects!

We have structured the main lessons throughout the experiences, insights and approaches from each chapter and case within this collaborative book. From the interviews, case studies and stories we found eighty lessons that can be applied to many cities around the world. We distinguished several categories. First we will look at two entirely different situations—new areas and existing areas—and both require a different approach.

Scroll down for all 80 lessons per context or download the PDF file below.

Public space should be the backbone of each new development plan – not the space that is left over after everything else was planned. Good planning deals with the functional and rational side, but if there is one lesson we can draw throughout all the contributions in this book, it is that planning should take into consideration the pedestrian’s experience, human behaviour and emotions.

In new areas, it is important to use the criteria from the start as requirements for building and street design for a good city at eye level. Equally important is to develop a strategy, placing these criteria as nonnegotiable on the one hand and to reward good behaviour on the other. New York and Seoul have developed similar bonus systems: if an owner creates public plinths, he is allowed to build more. The strategy ideally involves simultaneous (place) management on the level of the entire street or district, instead of each building managing plinths and spaces for itself.

By splitting the ownership of plinths from the rest of the building, and make them into one portfolio for specialized owners. This way, the tenant mix can be regulated and managed, getting the right balance of functions in the right zones and in relation with the pedestrian flows; and this way, in public space, activities and activating places can be programmed.

Quick wins, building trust, gradually allowing for multi-layered use and involving diverse ownership are crucial elements for plinths and placemaking. Changing existing areas is a matter of combining a hands-on, ‘lighter quicker cheaper’ approach with a long-term change strategy. In terms of regulation, changing an existing situation calls a ‘carrot and stick’ strategy: rewarding good behaviour, but also intervening if necessary.

When it comes to the strategy for existing areas, the most important element is to build community networks: active property owners, entrepreneurs, visionaries, residents, experts and ‘zealous nuts’. With this community, campaigns and great communication can shape a different type of street or place than is normally used.

In existing urban areas, change begins with a shared interdisciplinary analysis (as described in the chapter on workshops and games). Sharing ideas for solutions, creating a strategy to deal with diverse ownership, and establishing co-creation and networks are crucial. Each area has its own context, and requires a different strategy. For example, take a look at the buildings around a space. Some buildings have a good relation with public space already; others may have good façades but need better programing or are vacant; and yet other buildings need a complete physical makeover and a longer term approach to enable a better relation with the street.

Next to the difference between new and existing areas is the matter of scale. Changing a place, a larger building or a street is different than building a new area of several thousands of residential units, or transforming the experience of a complete city centre or city district. Working on streets and places requires concrete interventions, workshops, shared street visions, place or street management in networks with the community, developing coalitions of owners, and using instruments such as Business Improvement Districts (BID).

Working on larger areas involves a deeper level of analysis on a larger scale beforehand. For instance, obtaining a better understanding of pedestrian flows through the entire city centre (day and the night) and the source points for pedestrians; analysing ownership of land and buildings and the development of property value as an indicator of change; examining the ‘softer’ qualities of various meeting places. In-depth mapping of plinth functions, vacancy, and current and future projects for the next twenty years will deepen the understanding of future needs. Short-term actions can then bridge missing links, for example, in the network of pedestrian flows. The long-term strategy can, for example, develop a finer street grid with each development taking place over the next decades.

The strategy will also be different for areas with different functions. For retail areas: create a great and rich experience for pedestrians by street, place, and portfolio management, and develop coalitions of entrepreneurs. For residential areas: create a good connection between the house and the street on the ground level, allowing great “homey” hybrid zones where residents personalise their space with a table, chairs and plants, creating great sidewalk experiences. In areas where businesses and offices are dominant: create diversity and avoid (or change) long and boring façades by creating smaller units and bringing the inside out.

A sense of place is at the heart of each of these. In the long run, it is important to reach more mixed, flexible area, that can ‘breathe’ throughout the decades and centuries. True sustainability comes into being when areas can adapt to the ever-changing desires of society and the economy throughout each decade. When successful, these areas are well-loved by their users for their public space quality and their unique ‘soul’, and when the users feel invited to make a range of small and large investments throughout time, creating a sense of ownership.

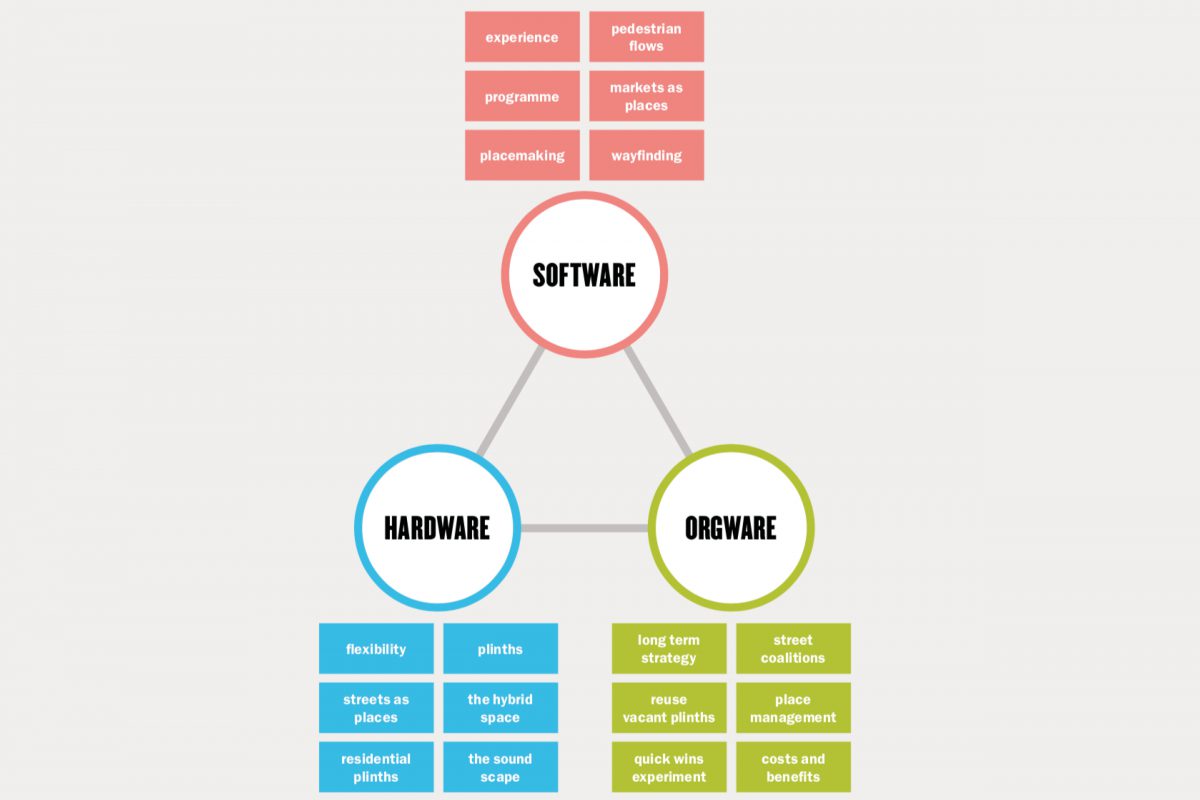

New or existing, street or city, shopping or residential; however different these situations are, creating a great city at eye level is always dependent on the triangle of use (software), built environment (hardware) and coalitions and tools (orgware).

We have taken the lessons throughout all the great contributions in this book and divided them in these three categories. To read more about a certain lesson, just follow the number behind it to the list of the chapters and cases. Some lessons refer to chapters from the first edition that can be found in the selection stories.

The first and most important part of the triangle is software: the users, their movement patterns, the experience of the city at eye level and the programme, land use, or zoning.

We are not only rational beings, we need the emotions of the city’s experience as well. Experience is important for the city’s users, and for the local economy. Sense of place and good plinths are crucial for this experience.

1. Focus on life in buildings and between buildings, as it seems in nearly all situations to rank as more essential and more relevant than the spaces and buildings themselves.3

2. Make your city well-formed, distinct, and remarkable; invite the eye and the ear to greater attention and participation. Improve the fabric of your city through colour, texture, scale, style, character, personality and uniqueness.3

3. Create small shops with open façades and make users feel at home: they create a warm city and allow for movement between the public and private, which creates interaction, meaning, histories and narratives through which we become attached to the city.4&10

4. Improve walkability. Aim for proven success factors: density of amenities, street connectivity, proximity to large green areas, regional accessibility and building design. Make interaction meaningful and comfortable and enhance the city’s quality of life.38

5. Create great plinths. The ground floor may be only 10% of a building but it determines 90% of the building’s contribution to the experience of the environment.1

“You can’t build a snowman, unless it’s snowing.” We can design the best buildings, plinths, streets and public spaces, but they are nothing without users. If human behaviour and its context are better understood, city centres can be managed in a more strategic way to optimize attractiveness and improve their economies.6 Putting users first means to simply imagine what it would take for women, elderly, children and disabled persons to feel at home at night.5

6. Develop your fingerspitzengefühl, looking at walking routes and busy – but not too busy – streets.12 Link new plinths to the urban route system.7 And base your pedestrian movement strategy on thorough data from costumer experience surveys.6,21&24

7. Provide users with convenience, but with surprise too.21 Create accessible, open plinths, with a veranda feeling, and attract more people and improve urban economies.4&6

8. Create a balance between pedestrians and car traffic to combine busy pedestrian inner cities with a through-traffic function.24 Do not allow the car to become dominant in important places.7 Work on the overall accessibility of the street for delivering traffic, residents, and visitors by car.33 Living, working, shopping, recreating and traffic, also the car, must be mixed as much as possible; streets where cars have been banned have the problem of being dead at night.5

9. Create safer and better entrances, not lavish foyers armed with guards, doormen and cameras, but a semi-public space.8

10. Size is not always the solution. Make shopping streets attractive, not longer: a stretch of 1.6 km can already too long to function as one shopping street, especially outside the city centre.30

Placemaking is to make places where people want to be, and share life together. Beyond building for everyone, placemaking means building by everyone, rather than by political, or corporate powers and personal egos. Think of public, rather than private interests; add symbolic values to details, and generate outputs for the enjoyment of public life.43

11. People activate urban spaces and reinforce the identity of place. Develop a programming strategy for urban activation on top of the urban design and the planning framework, both on a macro and micro scale.39

12. A good street is a series of places.44 A good place has at least 10 good reasons or activities to be there. Create “triangulation” by piling up activities in one place, leading to interaction.53

13. Aim for solutions that are lighter, quicker, cheaper. They can be temporary. If an intervention doesn’t work, experiment and try again. Placemaking is not about using more money; it’s about getting more return for the money.44

14. Involve developers: it is also in their interest to attract more people and more money. In the end, we’re all interested in the same thing: to create street life and new types of public spaces.44

The software is made up of the pedestrian’s experience, use patterns, and the programme (land use, function, zoning) inside the ground floor spaces. Shops may be the first things we think about when we work on active plinths, but we simply cannot plan retail everywhere. We need to think about other functions such as small businesses, fashion, leisure, care, food and last but certainly not least, housing.

15. To make a ‘Great Street’, a new function is needed every 10 meters (maximally). Offices are not the best contributors to active streets. Housing, if not too mono-functional, adds activity and safety at night. It is the mix of functions that creates great streets: shops, cafés, restaurants, school functions, houses and workspaces.01

16. Use remnants from the past as identity carriers.18 Learn from examples such as well-loved buildings, photos, historical events, famous people, old shopping fronts, public art or historical elements in the streetscape.

17. Look at new upcoming functions in areas with vacancy, such as co-working spaces, temporary “meanwhile spaces”, restaurants and cafés, social functions such as elementary schools, and most of all residential living on the ground floor. Due to online shopping, it is clear that we cannot solely rely on shops to create a good public realm.01&13

18. Carefully consider mega-shopping streets. They may lead to monoculture and make the street vulnerable— maybe vibrant but sometimes too crowded during the day, but deserted in the evening.07

19. When it comes to shops, select creative retailers for their plinths, and they will invent original ways to display their goods and draw people inside.28 The big chains play a role, as long as they are not allowed to dominate. It’s the smaller shops and spaces that are the real image builders.21

20. Consider food, fashion, design and authentic ethnic shops to provide interesting plinths in urban regeneration areas. They also draw positive new attention to these areas.22

21. The self-employed (freelance) economy is growing, creating a need for meeting places in the city centre.12 Create spaces for entrepreneurs. Start-up operations need a basic space with a flexible contract and some basic facilities.34

22. Single-use office locations with poor public transport are a toxic combination resulting in very high office vacancy. Add new uses to the office element to improve the functioning of the location, such as housing, restaurants, fitness centres, food and non-food stores, art exhibitions and leisure.17

23. Allow spaces like the Flemish garages to stay a part of the street, as they generate flexibility for unexpected uses such as cafes, shops, car repair garages, start-up spaces for entrepreneurs, workshops, lot sales, parking, import and export–in short, urban life.14

Use wayfinding to enhance the user experience in the urban environment, to help people reach their destinations in the easiest and most effective ways possible, to promote behaviour by stimulating people to walk a specific route, and support the local economy by attracting people to destinations that need more visitors.41

24. Work towards intuitive wayfinding, rather than to offer sequences of instructions, which is effective but also inflexible. Offer a fine balance of structure and differentiation. Group space into destination zones, identify local spatial zones, and accentuate elements such as entrances, exits, paths and junctions.41

25. Effective wayfinding design cannot be ad hoc installed. Explore what symbols hold special meaning

for the users, using insights into ergonomics, local rituals, personalities, cultural heritage and characteristics of place. Use thoughtful, meaningful research and deliberate application of interventions.41

For street activation, markets and buskers are crucial. Cities have grown from markets and markets have been the ultimate way for people to meet and conduct business. Markets provide a great, human experience for the city at eye level. Buskers (street performers) are a viable tool for rejuvenating public spaces. Busking is high-impact and low-cost. No infrastructure is needed; just an artist, performing for tips. Buskers prompt social interaction on the street level, create intimacy and allow people to feel comfortable and safe. They provide live entertainment that low-income citizens can access and enjoy.61

26. A good market has a mix of products and people, and above all it is a great place to be. For great markets, introduce a good mix in management groups. Include citizens and consumers with an advisory role in market management.57 It’s people who power markets. Create flexible parking lots that can become a market for one day, and add places to eat, and places for musicians and street artists.57

27. Markets are important for local small-scale vendors. In areas with low income, create a market where the city does not charge the locals to sell their goods nor for the space to sell. Enable local people to earn a living, develop their entrepreneurship, and take a first step on the social mobility ladder.57

28. Informal markets thrive on public streets. An old tree, a wall, or a bus shelter can be used to hold up the temporary frame of these roadside stalls. Such markets provide cheap buying options to the large lower middle-class population. At the end of the day, they are dismantled, packed and carried away.52

29. Approach busking as an asset to be encouraged rather than a problem to be solved. To get the best busking talent, cities must make the best buskers want to work there. Develop busking polices and guidelines in cooperation with the city’s busking community.61

The second part of the triangle is the hardware, the shaping of buildings and streets.01 Starting from the users, we can get to a more people-centred approach for public space. Good buildings, plinths and streets cannot be taken for granted. Many post-war areas have been developed from abstract urban and rational design conceptions and housing requirements rather than from the perspective of peoples’ everyday needs for good places and plinths.19 As buildings get bigger and bigger, more and more ground floor is taken up by service and security related to the companies inside, and with that come big, blank walls.08 They harm the functioning of a good street. Empty ground floor spaces impact neighbouring businesses and contribute to blight anti-social activity.13&19

We are changing the question from “How many cars can we move down a street?” to “How many people can we move down a street?” Build the foundations of a good city on human observation – engineering has a very small role in something as organic and human as streets.50

30. Create intimate streets for pedestrians with bold design elements, lighting, street furniture, trees, artistic details in the cement, parklets.24 Solve the barriers that block the natural walking routes for pedestrians: traffic, canals, horizontally-oriented buildings, and wide auto-oriented buildings.06

31. The balance between ‘place’ and ‘movement’ in the city calls for improving the balance between fast and slow transport. A main element of success is prioritizing pedestrians and slowing traffic in the city, without eliminating motorized traffic. The pillar is making busy and quiet places at the same time.49

32. Informal uses in public realm can be stimulated by elements that are just as high as seating elements, but are not designed as such. These can be for example staircases along the water, high edges along planters, or just objects that can be positioned in different ways. Switching on/off water elements creates spaces suitable for organizing events whilst on quiet moments the joy and pleasure of the water element turns these spaces into an inviting place to stay.49

33. The length of the street should be measured according to the sum of walking along shops opposite each other. If a street entices people to cross while shopping, the experience of the street becomes longer.62

34. Design bike routes to complement shopping streets; take into consideration that attractive streets attract people and that cyclists use the busiest streets because they are more fun.04

35. Use the infrastructure constructions for the plinths of the city, and provide new urban spaces and opportunities to interact and gather. At ground level these structures often form a barrier between neighbourhoods and have a blank façade. Redevelop these spaces into public places with markets, parks and playgrounds, and commercial and cultural plinths.51

The plinth is the most important part for the building’s relation with the street. A good design of shops and storefronts, of houses, of office buildings and of entire streets can lead to high quality, effective plinths. Unfortunately, we see a lot of bad examples too. How can we get better buildings, more open to the street?

36. Approach the design process from the outside to the inside, from the street to transition zone to the building; in designing, the street must be considered as a place to be.07 Let ground-floor architecture play a key role. Lifeless, closed façades pacify while open and interesting façades activate urban users. The overriding planning principle has to be: first life, then space, then buildings. Buildings and city spaces must be seen and treated as a unified being that breathes as one.46

37. Our senses are designed to perceive and process sensory impressions while moving at about 5 km/h: walking pace.46 Create many different surfaces over which light constantly moves to keep the eyes engaged. Create richness in sensory experience, diversity in functions and vertical façade rhythms.06

38. Create high ground floors. The height of the ground floor is important for adequate indoor atmosphere and sunlight, and for the flexibility of non-residential functions. The proportions of the building and its façade related to the profile of street matter considerably.07 Demand that the ground floors of all buildings are at least 4 m (13,1 feet) high, to accommodate for commercial, retail, or other business.07 Especially require corner plinths to have high ceilings and transparent windows, and provide them with mixed-use zoning, to allow corners to become a café, restaurant, a dwelling or office space.25

39. Learn from the 19th century method of transferable retail spaces in the plinths. The small scale, private investments and construction mode of ‘building on demand’ enable urban neighbourhoods to adapt easily and quickly to changing demands in economy and society.10 Reduce ground-floor rent in order to secure small units, many doors (minimum 10 per 100 meters) and an attractive mix of units facing the most important pedestrian spaces and routes.46 For an attractive storefront, create small shops. Shops that are too broad, such as supermarkets and large retail chains, lead to closed windows.33

40. Create a mixed urban district or areas with an urban density; no homogenous office areas or suburbia.12 Make ground floors diverse and offer constantly changing, vibrant, engaging, and welcoming environments.13

41. Anything that takes attention away from the storefronts is problematic. Avoid sudden set-backs in the property line, large-scaled columns or pillars, and “dead zones”. They interrupt the walking route and vision line, creating difficulty for the shops to carry out their goal: inviting people in.53 Supermarkets are a necessity for a residential district, so fit them in the urban block: either on the ground floor with supporting shops around them, underground, or on the first floor.07

42. Design and build mixed-use, multipurpose, non-specific buildings and plinths that can absorb many functions over time.07 Adopt a lay-out in which residential space, retail space, shops, and working space were constructed in the same street, even in the same building. The construction method must make quick alterations of property functions in the easiest way possible, in order to meet actual demand.10

43. The Japanese Machiya is an inspiration for its flexible façade; opening and removing the façade needs to be done easily. Plinths today could offer the same flexibility, allowing for an incredible amount of possibilities and freedom for the user. The openness of the Machiya blurs the lines between the inside and outside, creating a wholesome sense of responsibility and community. When borders get soft, people take care of their environment and stay connected.40

Special attention must be given to residential plinths. Not every area can be filled with shops and cafes, and still, more residential areas can have great streets too. Embedding residential buildings in the city requires a good plinth, but also a good position in the street, the proper width of the sidewalk, orientation to the sun, presence of a courtyard or garden, and a solution for parking (inside, outside, underneath).48

44. Involve the public space in the architectural designs to create a place that provides for encounters between its users, the hybrid zone. The entrances of buildings can for instance create inviting gestures towards the city.48

45. Create a “veranda feeling” in front of the house (a recessed hybrid zone) to strengthen the social climate. For children the sidewalk is an ideal playground because surveillance is naturally present, as already was noted by Jane Jacobs. Intensively used sidewalks generate social control on which parents can trust and children can benefit by.48

46. In housing projects, don’t use too much glass on the ground floor. Transparency is required in every program, but in practice all large glass surfaces are closed by curtains for privacy. The result is a closed façade. The ground floor can be slightly elevated above the street level by 2 or 3 steps, causing a small difference in elevation and hence privacy.48

47. The actual use of the transition zone to the street depends on the introvert or extrovert attitude of the residents. Extrovert urbanites who are outside a lot and have lots of contact with their neighbours appropriate even the public area. More private residents use the transition zone to the street less.48

The hybrid zone is the space between the private and the public realm, or perhaps better said, the place where these two meet. Hybrid zones are important contributors to the experience of the street, perhaps not accessible to enter, but still accessible by sight and smell. They make streets feel personal and intimate, as if the living room was pulled through the window to the street. People use the hybrid zone to increase their privacy, making the hybrid zone some sort of a barrier and creating safer neighbourhoods. Nearly 80% of the informal contacts between neighbours are initiated from the

hybrid zone.09

48. When we are designing the plinth and the street level of the city, the first thing we need to do is design its hybrid zone, the place where it interacts with its user.11 Avoid a clear-cut distinction between public and private in favour of semi-public space: the city is about porosity, the blurring of edges.08 Pedestrians feel more at home if this hybrid zone shows signs of human activity, instead of just hard blank walls.09

49. On a residential level, people use the hybrid zone to increase their privacy, making the hybrid zone some sort of a barrier.09 Design the plinth so that it offers something to the passer-by and reserves a bit for the resident, for example with small front gardens or private zones along the sidewalk.07

50. In shopping streets, increase diversity by allowing shop owners to put their goods outside next to the façade. In office areas, locate the public functions on the ground floor as much as possible, for instance with outdoor cafes and terraces.

Although the looks of a city are important for its appreciation, sound is more often responsible for how we feel at a particular location. We can choose what to look at, but not necessarily what we hear. For a good experience, make a strategy for the urban acoustics, the city at ear level.55

51. It is a common misconception that people prefer silence most of the time. Aim for variation (a lot of different sounds), complexity (no monotonous, repetitive sounds) and functional acoustic balance (the space you are in should not sound bigger than you see it).55

52. Use three ways to design for sound in public space: absorbance (trees, shrubs, hedges, certain sculptures), diffusion (avoid hard and smooth surfaces, use irregular façades), or masking (mask irritating sounds by introducing less intrusive ones, such as water sculptures).55

53. A plinth with interesting activities often sounds good. Many modern office buildings have a hard glass surface on the ground level (or even two floors). These are an acoustic nightmare. Use terraces, workshops, open plinths, stores and personalised hybrid spaces, like small front gardens and hedges, to diffuse sound and to generate rich textures of sound.55

The key to good plinths is neither only in design, nor only in an economic approach. Good plinths are obtained when both are linked. Then, the third crucial element is the orgware: the organisation of functions; the daily management of shops, plinths and streets; and the portfolio maintenance of plinths.

Plinth Strategy requires a combination of short-term, hands-on action and a long-term strategy and perseverance over the years.

54. Quick wins are a guide for the long-term strategy, and are needed to demark the new approach and win trust among property owners and tenants. However, without a long-term change policy these quick wins remain window-dressing. The combination involves four elements: regulation, stimulation, changing missing links and a network campaign.36

55. Make your strategy long lasting: changing and improving plinths in an existing urban structure takes at least three generations and requires a long-term vision for restoring the urban fabric, based on a deep historic understanding of how the city developed.(05) Be modest: we must realize that we only deliver small contributions to centuries old systems.07

56. Use re-imagination as a tool for the process. The ability to imagine that a space can be different already creates a possibility to change it. A street can be a market, a park can function as an open-air cinema, an abandoned alley as a gallery. Imagination is a powerful tool we can use to change.43

57. Use fun. Create a joyful and fun way of discussing important urban issues and engaging people in the creation of public spaces. For instance, putting Band-Aids on holes in the sidewalks, introduce games, musical instruments, sports activities for kids.56

58. Temporarily close off streets for cars at certain moments of the week, for instance Sundays from 6.30am to 11am, like the Equal Streets initiative in Mumbai. The immense amount of people taking their morning walk, mothers strolling with their babies, children skateboarding and cycling, musicians humming in the background are a first step towards more structural policy decisions.52

Allow communities to become engaged. The city at eye level and placemaking are about that deep attachment. It’s emotional. It’s something that people own; it’s their process and their outcomes.44 When the municipality/city is the only responsible party to improve the quality of a street, no effort should be undertaken (yet). The cooperation and willingness of the community, entrepreneurs and/or building owners to embrace an improvement process is absolutely vital.36&54 How the city involves itself in the development of the city is crucial; debate and resistance sometimes take a long time, but eventually lead to better urban design.05 We can learn lessons from the informal, self-organised city in terms of how human scale, variety, high density, flexibility and little car use contribute to a pleasant space. Creating a framework for self-organisation should not just be a fashionable concept, but an imbedded planning strategy.60

59. Create a continuously dynamic process, not a static set of amenities, objects or activities. The process empowers everyone including residents, businesses and local government as co-creators and modifiers of place.44&54

60. Look for the (unofficial) leaders, the “zealous nuts”, the visionaries with a poorly developed sense of fear and no concept of the odds against them. They make the impossible happen.44

61. To get started quickly and easily, involve the network into a shared analysis and generating new ideas for the future, organize a place and a plinth game. Walking and talking in smaller groups, analysing the street together based on everyone’s intuition, coming back with shared ideas – it all creates a different mind-set. It allows for interdisciplinary acting, and breaks down barriers, bringing people together to start take ownership and create their own places.45

62. As the first actions lead to success, let the community take on bigger challenges. The initial actions gradually shift to a type of street, area or place management, inviting new activities, testing, learning from actions and improving. To really come to change, a mix is needed of ‘Carrot & Stick’, including both strictly implemented and maintained guidelines, and tempting new initiatives by rewarding good behaviour and showing best practice.45

The street, plinth or place manager is the person linking property owners. The manager is a key to successful ground floor spaces, shifting from single buildings to blocks or entire city streets. Independence from project developers and landlords is a preconditionto develop a long-term business model and investment strategy.32 The manager must be impartial,62 and think in terms of a process, not a final image or a blueprint; observe bottom-up movement and facilitate it. A street or place should not be seen as a project with a beginning and an end in time, but always as an organism that grows over time and that requires constant attention.33

63. Shift from a building logic to a street logic to enable a plinth strategy.31 Single ownership, like at airports, enables smart portfolio strategies, exceeding single unit strategies and creating a holistic experience which costumers will not forget.21

64. A long term vision with regulation, zoning plans and aesthetic policies can be the base of a strategy, but brokership is necessary to take the next step. Brokership is the quick exchange of information about e.g. vacant shops or socially wanted activities.36 Finding the right programme for the plinth is a task for the landlord or for specialised experts, not for developers – it is a special business.12 Landlords usually are very unfamiliar with the special market of plinth functions and are satisfied most of the time if they have contractors for the upper 90% of the building.

65. Create added value by a well-balanced portfolio through a three-point strategy based on revenue, quality and image.32 Individual merchants can make small changes to their storefronts. The very nature of being a merchant is to think about the inside—the products they sell. Take the merchant by the hand, walk outside, and show them their building. In most cases, small, inexpensive additions can be made: a new imaginative hanging sign, a colourful awning, creative window displays, a bench for sitting, or merchandise on the sidewalk.53

66. To increase impact, cluster plinth initiatives together and launch them at the same time.26

Good plinths may come with higher upfront costs, but they also lead to greater benefits. Good plinths are in the best interest of the urban economy, and not only because of consumer spending: those involved in the knowledge and experience economy require spaces with character, a good atmosphere, a place to meet and to interact.01 The knowledge-based economy is founded on face-to-face contact in breakfast bars, lounge areas, libraries, galleries, pubs and coffee corners.10 Understanding the underlying financial patterns reveals why good plinths do not come about by themselves and the actual interests of different parties involved: the consumers, the citizens more in general, developers, owners of the building, land owners, tenants and designers.

67. Develop an investment strategy based on pre-investment or involve partners who can help. Making a good plinth is expensive due to high construction costs and required pre-investments. Pre-investments are needed to create future value for the street and city.12

68. Involve partners that allow a mixed-use strategy in your approach. From a developer and investor point of view, mixing uses in one building in particular adds an element of complexity and risk, with higher levels of specialisation required (design, promotion), more intensive management requirements and perceived diluting of investment value. Nonetheless, mixed-use office areas do generally perform better than single-use office areas: the combined vacancy in mixed-use areas is lower.17

69. Keep properties safe, clean, relaxed and easily understood. If visitors’ expectations are met or exceeded, they will remain three times longer and spend more money than in an unfriendly and confusing structure.01

70. Make it clear that good plinths are in the owners’ interest. Property owners benefit economically through the security of active tenancy, reduced costs for empty property, and prospects for future uses.13 Where programming plinths leads to value creation of neighbouring property, larger landlords, residents and entrepreneurs can be the shareholders for re-development.18 Project developers and landlords on a speculative base tend not to think in the long term. Often they set for the highest return on their investments, resulting in well-known, run-of-the-mill tenants. Involve real estate owners at an early stage in new plans and strategies in order to convince them that a long-term vision is better for everyone.32

71. The municipality must consider their financial strategy.12 Short term financial gain and good plinths are often not easy to mix, but good plinths can be part of a sound long term financial strategy that leads to value creation for the property, the area, the users and the local economy. Set the land price of ground floor space rather low, at the level of residential space, to allow for commercial diversity.17

In areas that need reutilisation, reinventing plinths can be one of the new instruments. We have seen many forms of this throughout the book: from changing the image of entire shopping streets to turning garages into small businesses.

72. Monofunctional office areas are not inviting in the long run. If you want to change them, adapt an overall strategy for the whole area, diversify marginal spaces, develop a night-time identity and open up buildings with renters who relate to the street.37 Revive modernist CBDs: add significant numbers of housing, create a finer grain in the street pattern by opening up underutilised alleys, among others, and introduce a place-based policy.39

73. Slowing down the revitalisation process allows for ‘periods of quiet’ for all partners, especially existing residents, ‘slow urbanism’ ensures flexibility and energy among the partners, as well as a steady stream of investment, staving off impacts of the crisis.26

74. Shop re-parcelling could create new opportunities to an imbalance of shop vacancy and the demand for large retail space.35

75. To assist small businesses looking to relocate in laneways and other underused areas, introduce a Fine Grain Matching Grant. Fine grain businesses are small scale, diverse and innovative business engaged in specialist retail, hospitality or entertainment and encourage activation of underutilised spaces such as city laneways and basement spaces.39 Rebuild vacant garages into small, low-rent spaces for entrepreneurs as a way to develop their businesses.34

76. Generate sustainable entrepreneurship by striking deals for tenants to pay 1€ less rent for each 1€ invested and letting them invest in themselves.29

Vacancy of plinths is an important new theme to address. This book covered several examples of business models that address this issue. Temporary use, if organized and managed well, has been a successful strategy. Temporary use can improve the financial and social value of a plinth, a building and its surroundings, and can be a useful regeneration tool.

77. Meanwhile use is a good way to test new uses on a high street15 and through meanwhile use we can help our high streets to adapt to an uncertain future.13 If a building is for rent, the temporary plinth function should cast the message of availability.15

78. Without proper policy, temporary use is delivered to the good will of the property owner.15 Good vacancy management is knowing the property owner’s strategy, seeing the building’s unique possibilities and limitations, and knowing many end-users and initiatives with a good idea to fill a plinth.15 Learn from the vacancy legislation in the United Kingdom where landlords of empty property have to pay 100% of business rates once the property has been vacant for three months.13

79. To solve vacancy develop networks among potential renters as well as policy makers and property owners. A festival of empty shops can be a great start to raise awareness in these networks, and test what works.47 Acquire close contact with both policy makers, property industry, creative industries, social enterprises and local government to reuse vacant plinths.13

80. To regenerate an entire area, including the area’s eye level, develop a shared ownership with the tenants, take at least 10 years, create an atmosphere of experiment among the key stakeholders (building owners, city, tenants), and use contracts with new tenants that the plinths must have a public function and appearance.63

(1) Hans Karssenberg, Jeroen Laven: The City at Eye Level

(2) Jouke van der Werf, Kim Zweerink, Jan van Teeffelen: History of the plinth

(3) Meredith Glaser, Mattijs van ‘t Hoff: Iconic Thinkers

(4) Thaddeus Muller: The Plinths of the Warm City

(5) Adriaan Geuze: A Thirty Year Vision for the Urban Fabric

(6) Stefan van der Spek, Tine van Langelaar: Walking Streams and the Plinth

(7) Ton Schaap: Designing from the street

(8) John Worthington: Semi-public Plinths

(9) Sander van der Ham and Eric van Ulden: Hybrid zones make streets personal

(10) Jos Gadet: The time machine: same building, different demands

(11) Samar Héchaimé: Deciphering and navigating the plinth (* website)

(12) Frank van Beek: A Developer’s Intuition

(13) Emily Berwyn: The Meanwhile Plinth

(14) Wies Sanders: A plea for Flemish Parking

(15) Willemijn de Boer: The soul purpose of managing empty real estate (* website)

(16) Gerard Peet, Frank Belderbos: Joep Klabbers: Uncovering Hidden Treasures

(17) Jeroen Jansen, Eri Mitsostergiou, Mixed use development from a property development perspective

(18) Henk Ovink, Hofbogen: a vision for the in-between plinth

(19) Arjan Gooijer, Gert Jan te Velde, Klaas Waarheid: Reinventing the ground floor after 50 years

(20) Max Jeleniewski: Marketing a City with Double Plinths (* website)

(21) Tony Wijntuin: The need to be different

(22) Mark van de Velde: Zwaanshals: generator of neighbourhood development (* website)

(23) Case Study – St Pancras International Station London

(24) Case Study – Valencia Street San Francisco

(25) Case Study – Sluseholmen Copenhagen

(26) Case Study – Het Eilandje Antwerp

(27) Case Study – HafenCity Hamburg

(28) Case Study – Distillery District Toronto

(29) Case Study – Neukoelln Berlin

(30) Case Study – Modekwartier Klarendal Arnhem(31) Case Study – De Meent Rotterdam (* website)

(32) Hans Appelboom: The importance of ‘local heroes’ in plinth improvement

(33) Nel de Jager: The neverending story of street management(34) Arin van Zee, Willem van Laar: From box to business, a low cost intervention

(35) Peter Nieland: Shop Re-Parceling (* website)

(36) Emiel Arends, Gábor Everraert – The Case of Rotterdam (* website)(37) Alessandra Cianchetta: Marginal Spaces at La Défense

(38) Alexander Stahle: Economic Values of a Walkable City

(39) Anna Robinson: A Finer Grain on Sydney’s Streets

(40) Birgit Jürgenhake: Japan: The Machiya Concept

(41) Camilla Meier and Wouter Tooren: Basic ingredients for successful wayfinding in our cities

(42) Ciaran Cuffe: Dublin after the Boom-andbust

(43) Francisco Pailliè Pérez: To Imagine a Space Can Be Different (44) Fred Kent and Kathy Madden: What is Placemaking?

(45) Hans Karssenberg: Take Action Now #1 – Organizing Street Workshops: the place game and the plinth game

(46) Jan Gehl, Lotte Johansen Kaefer and Solvejg Reigstad: Close Encounters with Buildings

(47) Levente Polyák: The Festival of Empty Shops in Budapest

(48) Marlies Rohmer: Embedding Buildings

(49) Martin Knuijt: The Ebb and Flow of Public Space

(50) Meredith Glaser & Mikael Colville-Andersen: The Cities of the Future are Bicycle-friendly Cities

(51) Mattijs van ‘t Hoff: Underneath Rails and Roads

(52) Mishkat Ahmed-Raja: Reclaiming Mumbai

(53) Norman Mintz: By the Power of 10

(54) Paulo Horn Regal: Culture Brings New Life to Porto Alegre

(55) Kees Went: The City at Ear Level

(56) Jeniffer Heemann: The Science of Joy in Sao Paulo

(57) Peter Groenendaal: People Power Markets

(58) Petra Rutten: Balancing Profits and Social Demands

(59) Case Study – Schouwburgplein Rotterdam

(60) Renee Nycolaas and Marat Troina: Spontaneous Street Life of Rocinha

(61) Vivian Doumpa and Nick Broad: Street Performing: Low Cost, High Impact

(62) Robin von Weiler: Keeping the Sleeping Beauty Awake

(63) Jeroen Laven, Gert Jan te Velde, Paul Elleswijk: ZOHO Rotterdam: Bottom-up Meets Top-Down at Eye Level