Keep up with our latest news and projects!

This chapter discusses outdoor play areas in Cairo, Egypt, from the children’s point of view. The aim of the study was to improve the play-area design in Cairo, by reconsidering the design approach and making suitable changes based on listening to children and their proposals. Overall, the focal point would be understanding that children don’t necessarily use objects as they have been originally designed, as they have their own perspective and can see play potential in objects that adults do not.

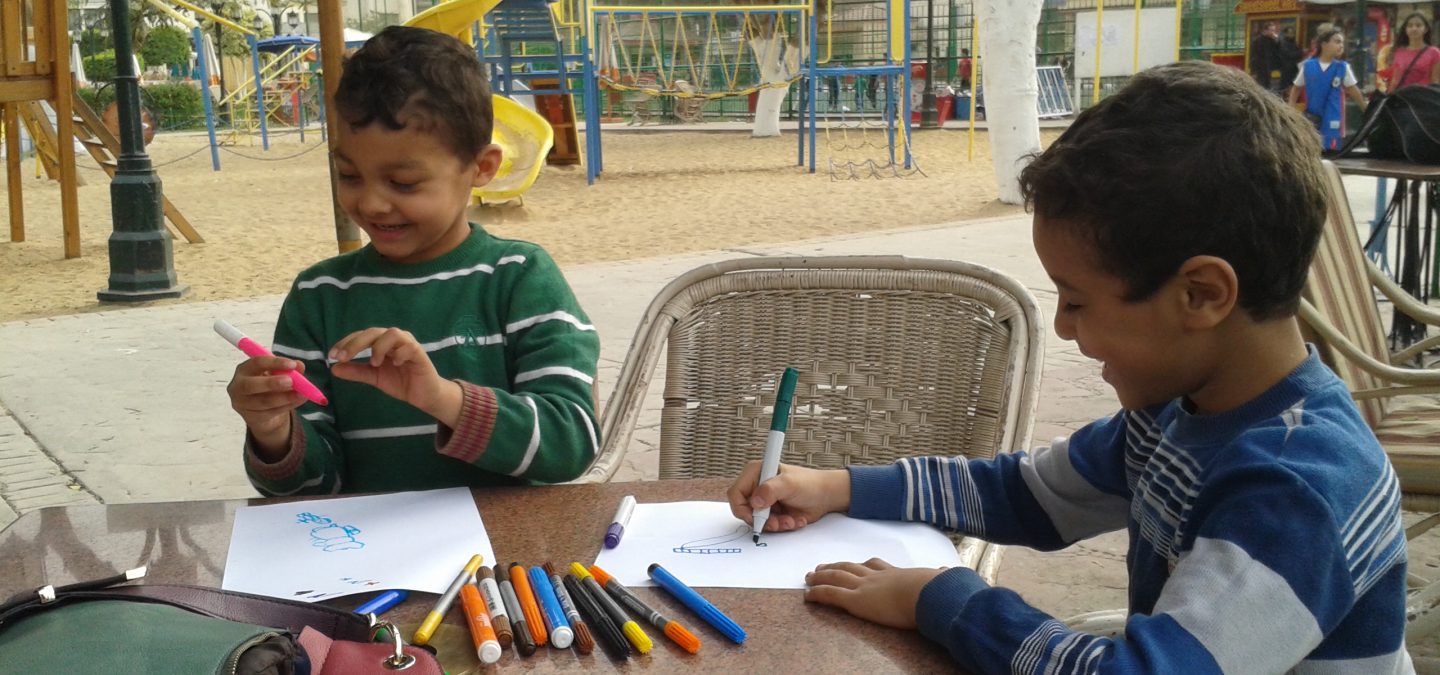

It has been noticed that outdoor play is disappearing from our world today. Nowadays, play is commonly in seats behind screens and virtual spaces, which has physical and psychological effects and does not compensate the benefits of outdoor play. (Tovey, 2007).

The design of play areas is the number one cause for this, whether it is unattractive, dangerous, wrongly located, or not maintained. But a greater problem is that it usually is NOT what children really want. (Beunderman et al., 2007). Traditional playgrounds make children segregated in a place with non-moveable play equipment with no opportunity for discovery and experimentation. These spaces don’t offer children opportunities to be creative in their play. (Ball, 2011).

Children Playing in The Past and Nowadays

Children Playing in The Past and Nowadays

A quick look at any Egyptian city’s urban fabric will clearly show the lack of public parks and gardens in residential neighbourhoods. Numbers refer that open areas range between 1.2% and 4.6 % of the total city area. Due to this 40-50% of Egyptian children don’t find an interesting area to play and tend to stay at home and watch television or rather play on streets, facing all types of physical, social and behavioural dangers, (Thoraya, 2010).

This is due to the limited options provided, especially for those who

are unable to pay much for their children to play, as the majority of play opportunities require relatively expensive admission fees. This availability problem is related to the fact that most areas grow gradually according

to growth in population and not upon previous planning. However, it is

not only a quantity problem but additionally, the design of these areas requires a specialised team of architects, landscapers and child playscape designers. This is rarely an option. (Thoraya, 2010). Consequently, the results are mostly traditional boring sandpits with metal structures.

Another noticeable problem is that adults generally make decisions on behalf of children and believe that children are not good enough to decide for themselves. (CABE Space and CABE Education, 2004). Unfortunately, planners see that participation gets in the way of making rational decisions. Yet, in reality, it is a rational decision to involve children as they are the client and user of space. Considering the fact that children differ physically, cognitively, and emotionally, this equally means that their perspective is also different from adults. They learn through senses and experiences. Children should have the opportunity to create their own activities and adults should present a supportive role.

The current design method starts with play providers leafing through equipment catalogues with a ‘let’s have one of those’ attitude. (Tovey, 2007). This only leads to stimulating gross motor skills, if any, while a quality play area involves developing other skills. When we start designing a play space we need to ask ourselves:

– What do we want this place to look and feel like? – What makes a good place for children and why?

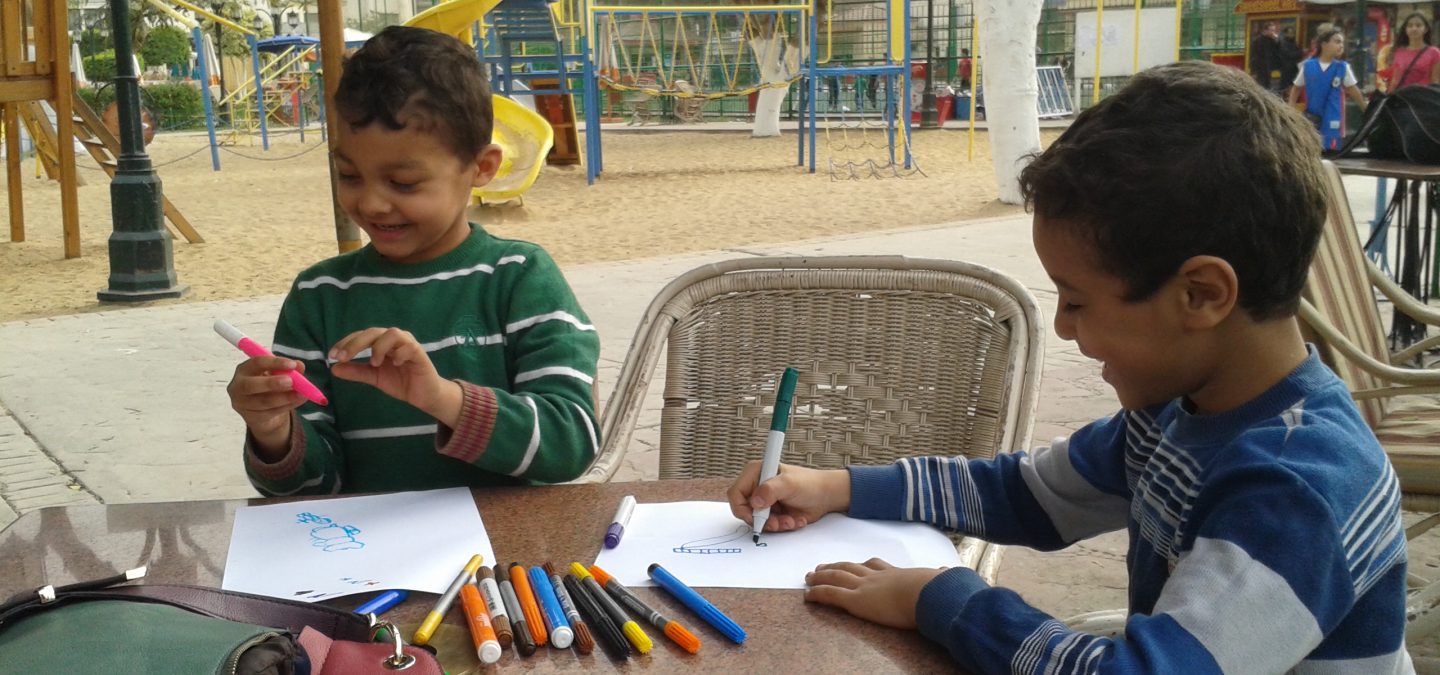

Hereby, listening to children is the way to reveal what children think, what they like, dislike, and how they see urban spaces. Their participation in design decisions and forming their own physical world has to be revealed through methods other than adult observations. Additionally, it is not only about spoken words, aside to traditional interviews and questionnaires, but also art-based activities like photography, map drawing, task-based methods (worksheets, diagrams, photographs, drawings, etc.) are more interesting to children and reduces pressure of an uncomfortable interview on them. A group of 20 children aged between 6 and 8 years participated in workshops in three traditional play areas in Cairo as sites, listening to the children and watching them play, as shown in the sketch below.

Play Site

Play Site

Watching the children play supported theories that natural elements, elevated places, and loose play parts encourage activities that have physical, social and cognitive benefits.

Listening to the children clarified that playing outdoors is more fun for them than playing indoors as they can perform a wider range of activities. They considered natural elements essential in the play area, not as a play potential but rather a background to play structures that they believed to have more purposes than their original designated and designed purpose. This was also reiterated in their drawings.

When it came to dislikes, some mentioned safety issues, falling from trees or playing on sand that contains small rocks and gets in their shoes, or exposed nails and non-maintained objects. Others discussed the quality of play on objects they found to be too boring, which mainly were swings and seesaws, not challenging enough, made for younger children or were too scary. A child mentioned wishing for a place to play freely and set up his own rules.

The case where children use objects in a way other than it was originally designed-for was noticed several times. They could use the seesaw as a balance beam and walk on it, or even play in areas not designed for play. A group of children was found to play with the cleaning equipment as they found this more interesting to do than play on the designed structures. Another boy was using the fence ropes to climb and swing on them, essentially neglecting all of the playing equipment.

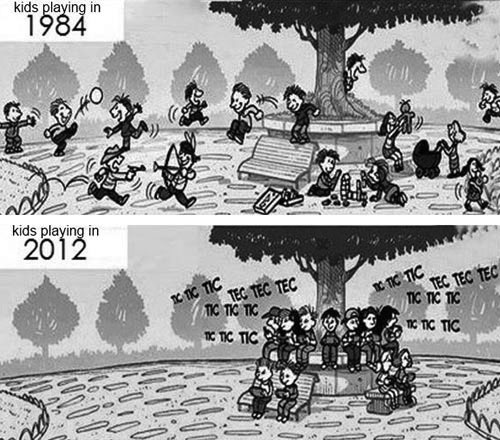

As a final mission of the study, children were given the opportunity to openly suggest new ideas and features they crave, as their involvement produces innovative play areas and builds a sense of ownership to the place and increases self-confidence. Amongst their suggestions were natural elements; water, trees, and animals as well as requesting the presence of mud and dirt to play with, adding water features to swim in, allowing play on grass and green areas and including animals in the play area that they can interact with. Treehouses were also a very common suggestion, as well as creative ideas like setting up a place for cooking and similar pretend games. A child mentioned a maze and tunnel to play adventurous games.

The following sketch resembles a play area zoning that could be generated from the children’s preferred ideas.

Zoning Children's Suggestions

Zoning Children's Suggestions

Parents, however, were concerned about two main issues: safety and hygiene in different forms. A clean fenced space with no smoke, loud noises or risks was an optimal solution for parent satisfaction.

To sum up, we can say that a play area designed to enhance children’s play experience should have a wide range of possibilities for play.

It should be flexible enough to accommodate different types of play – physical, social, and cognitive – as well as having rich varieties for playing in natural elements, elevated places and customised play parts. Playing in such a rich outdoor play environment is more beneficial to children’s development than playing in a traditional playground with limited opportunities.

It is only then that we can get a closer model to play spaces at the eye level for kids.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover more– Ball, D.J., 2011, “Safety, Risk and Play: Changing positions in the United Kingdom”, Speelom Seminar. Antwerp, Belgium. – Beunderman, J., Hannon, C., Bradwell, P., 2007, “Seen and Heard: Reclaiming the public realm with children and young people”. London: Demos.

– CABE Space and CABE Education., 2004, ‘Involving young people in the design and care of urban spaces. What would you do with this space?’ Retrieved on: 1-7-2012 from: http://www.thesquarecircle.net/ resources/medias/2317.pdf

– Dunnett, N., Swanwick, C., and Woolley, H., May 2002, “Improving Urban Parks, Play Areas and Open Spaces”.London: Queen’s Printer and Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

– Thoraya, Hoda. 2010 Principles of planning and design of open areas for children in the Egyptian city” Master of Science thesis, Assuit University.

– Tovey, H., Tina Bruce (Ed. of Debating Play Series). ,2007, “Playing Outdoors Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge”. New York: Open University Press.