Keep up with our latest news and projects!

It has already been mentioned in this book that children represent the future of a city. The quote of Enrique Peñalosa, Mayor of Bogotá “children are indicators, a city which is successful for children, is successful for all its inhabitants” is strengthened by research. The ability of children to roam independently, the amount of time they spend playing outdoors and their level of contact with nature indicate how a city is experienced by its inhabitants, in terms of health and well-being, sustainability, resilience and safety.

Several movements focus on ways to make cities more child-friendly. At the same time research shows a worrying decline in children’s use of public spaces near their homes for play. Only 21% of children play near their houses (outside in the street or in the area) every day, compared to 71% of their parents (ICM opinion poll).

In this article I will explore the following: what do urban children really need? And how to work towards those needs?

In a more and more institutionalized society, where time to play freely is becoming scarce, the importance of free play is increasingly more evident. It is exciting to see how the world is rapidly changing – an exponential increase in our technical abilities, artificial intelligence, robotization, and growing access to worldwide knowledge. Educators, leading businessmen and politicians agree that our children will need a distinguished set of skills to be able to profit from these improvements as adults. They will still need to build up their domain knowledge but at the same time learn different skills, ‘21st century skills’, like problem solving, innovative and creative thinking. And ‘soft skills’ will distinguish us as well; think of teamwork, empathy, understanding and persistence.

Research shows that – besides education – children develop these specific distinguishing skills mostly during play and specifically during free play. Outdoor free play provides many opportunities for social learning. The social abilities that children acquire while playing in public space unaccompanied by parents are particularly valuable (Daschütz, 2006).

Children do not feel as if they live in a city, their reference is the neighbourhood. According to Tim Gill, we should aim to expand children’s everyday freedoms, including their freedom to play within their neighbourhood.

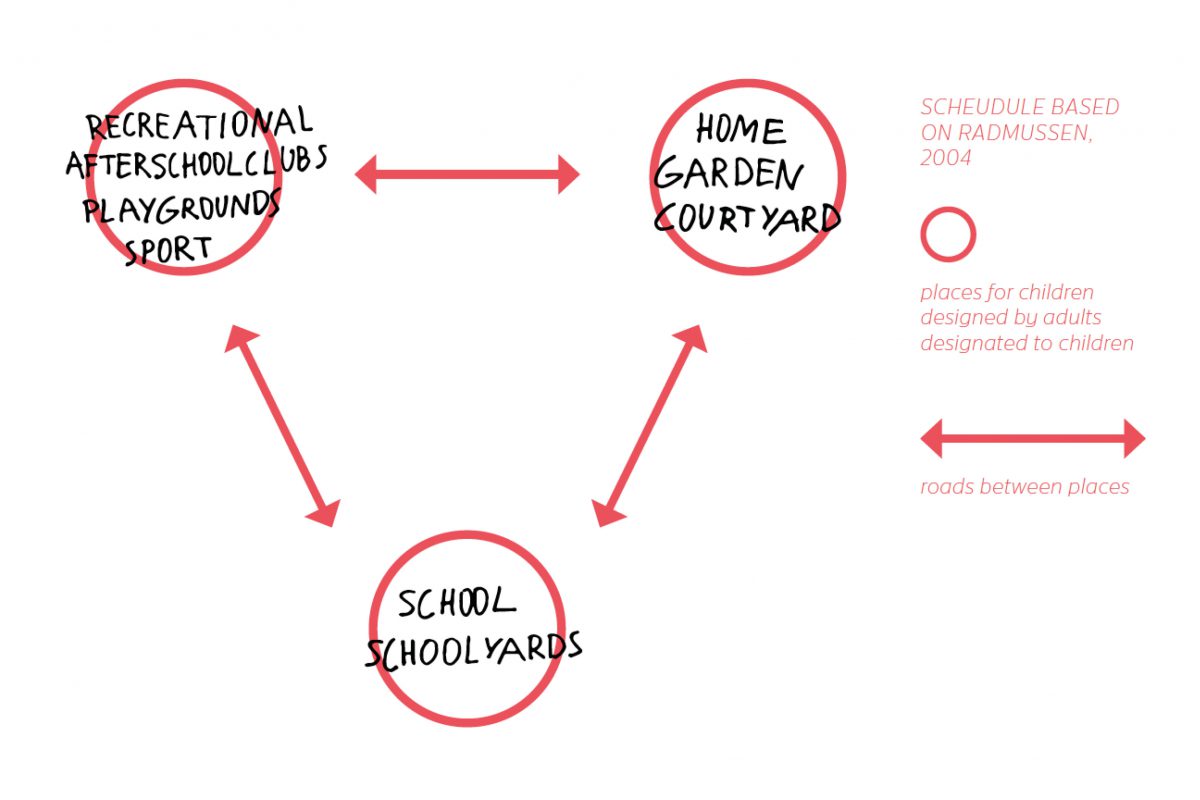

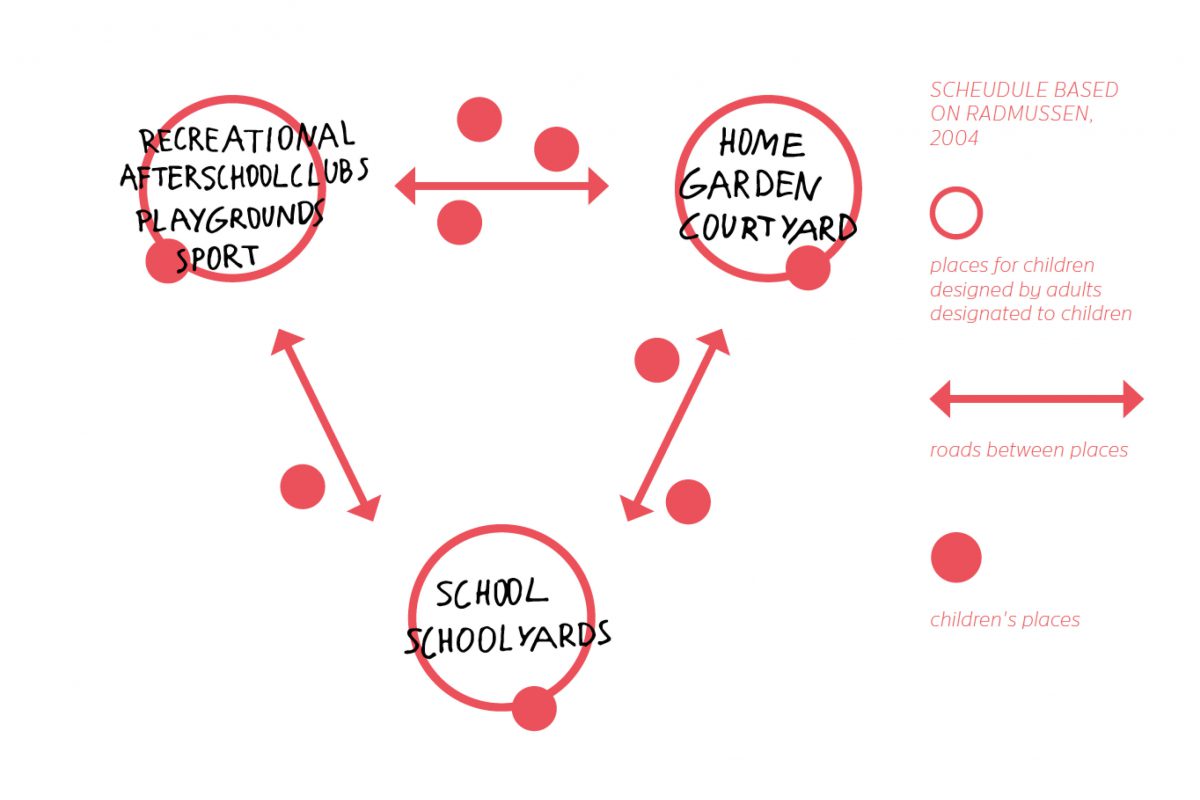

The everyday life of an average European child happens within an institutionalized triangle (Rasmussen, 2004), where the corners are (1) the home area (indoor & outdoor), (2) the school & schoolyard, and (3) recreation (after school clubs, playground, sports). These places for children are designed by adults. The legs are the routes between these places.

But if you ask a child to take you around its favourite places, it will probably point you to some new areas that are different from the formally designated ones. Kids’ favourite places are not the intended ‘places for children’, but ‘children’s places’ like neglected, informal or natural spots (see Valentine, 2004, 74-76/ Armitage, 2004). Children create their own emotional connection to these places, their own sense of belonging and even ownership.

The research of Baldo Blinkert (Quality of the City for Children: Chaos and Order, 2004) stresses the importance of such ‘functionally unspecific’ places, undefined spaces, which will be filled in by children themselves.

As adults, we cannot design children’s places. But by asking children and teenagers to give us a guided tour, to tell us about these places, and to map those which are important to them, policy-makers and designers can receive great insight. By adding these (their) places, plus the routes they take, into this extended triangle of Rasmussen, the starting points of a child-friendly neighbourhood can be set.

Let us look at opportunities for free play through the triangle.

The safer a neighbourhood is and the better adapted it is for pedestrians and cyclists, the more freedom we can give our children to move safely in between the ends of the triangle and find their own places in between. The sentiment of freedom has a lot to do with the attitude of adults. Differences in mobility behavior are in many cases linked to rules imposed by parents. For instance, many girls are allowed to move around freely only at an older age, for shorter periods and less frequently than boys. Vienna, for instance, is promoting transport by foot, bicycle and public transport, and focusing on safe atmospheric streetscapes to contribute to equitable mobility and increase the freedom of children and adolescents to move independently (Vienna research).

This is a fundamental precondition if we want to enable all children to play freely.

To decrease inequality between different communities, these ‘places for children’ should be inclusive to the public without entrance fees (cities alive, designing for urban childhood, ARUP). The tendency to take these designated play areas out of the public realm, by fencing them part of the day (schoolyards), or placing them in ‘privately owned public spaces’ (POPS) – housing compounds, coastal hotels and restaurants, parks with entrance fees, indoor playgrounds, outdoor play elements with fees – is threatening equitable access to play for all children regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds. If we want to design a city for all, we should defend our public space.

Neither the size, nor the amount of equipment make playgrounds better places for children (Yao Kangling, 2015). Adults talking about playgrounds, mention the division of space and its elements (sandbox, swings, slide). Children talk about the physical use of the places, their special meaning (best bushes for hiding), and the feelings that place evokes (“we are alone, nobody can watch us”) (Grau & Walsh, 1998).

Children play longer, are less bored and come more often if the area to play offers a variety of opportunities (Kingery-Page & Melvin, 2013; Stagnitti, 2004). Places to play should invite different types of play, not necessarily in terms of equipment, but by creating a landscape of diverse surfaces (sand, pavement, earth, shredded wood, grass, rubber), with simple minimal elements inviting children to create their own types of play:

These 7 types of play ensure that all children with their own favourite play – depending on personality, gender, age, culture, background – can find their own place within the area to play.

Discussions on inclusiveness often focus on children in wheelchairs, but there are numerous disabilities that designers should account for when designing play areas. The key is to differentiate and to design for abilities. Children with disabilities, just like all other children, want to learn new things (‘neophilic’), to discover and improve their abilities.

Ensuring a diverse spectrum of play types, and various level of difficulty (e.g. platforms at differing heights, with different ways to climb up these platforms: from stairs with railings, to ladders, steep ropes, monkey bars or climbing grips), and also differentiating the size of the elements, enables children of different ages to enjoy the space, according to their own emotional preferences, and individual physical or intellectual abilities.

Inclusive playgrounds should stimulate kids to play together on the same undefined places and with the same elements, which are accessible for children with all their unique (dis)abilities.

Design for Boys and Girls …?

Yet, inclusion goes further. Research still focuses on differences in play between boys and girls. For instance, boys are seen as being more physical, active, competitive and involved in rough and tumble games, while girls participate more in sedentary play, verbal play and in socializing activities. But in the current day and age, we should look at it as a unique play preference based on personality, not gender (boyish or girlish). Enabling diverse types of play gives children of all sexes equal chance to engage in the type of play they favour at the moment.

Gender segregation appears to be much sharper at school playgrounds than in street play. In school playgrounds, boys often dominate most of the (play) space and use large areas for games like football, whereas girls tend to occupy walled areas and seating areas which give them a sense of privacy (Thomson, 2005,p. 74).

The cause of ‘boys overtaking the playground’ is often in the lack of diverse play opportunities. Even small spaces can invite for a wider variety of different play types. If children can play more different types of play, then boys will engage in more diverse play and the space will be less taken over by football.

According to Karsten, the public playgrounds in Amsterdam host more boys than girls, especially in older age groups, and even more so among Moroccan and Turkish kids. Girls’ status as a minority on the playground is reinforced by the fact they go in smaller groups, less frequently and for shorter periods of time. Boys, on the other hand, enjoy more freedom and can roam around in the neighbourhood more freely than girls, who are restricted by the care for younger siblings and by domestic chores. (Janbor & van Gils, several perspectives on children’s play, garant). Creating spaces for older girls to play and socialize, next to the toddler areas might be one way to increase their freedom to play.

Children and teenagers who like to spend outdoor time with their friends in groups feel that they are often discriminated against because of their age. Within cities there is a negative attitude (intolerant adults) towards older children and teenagers, sometimes enforced by legal sanctions such as dispersal orders, which restrict young people’s freedom to spend time in the streets and areas around their homes. Their freedom in public space is limited, decreasing their opportunities for informal recreation which they need and have a right to.

Conflicts of ownership around play spaces between younger children and teenagers, is often caused by a lack of opportunities for adolescents to gather, play sports or socialize. Sufficient opportunities would enable both groups to find their own places to play and socialize. Think of undefined places for gathering, differently shaped sitting and hangout spaces, more nearby sporting or shopping facilities, multifunctional street sports elements combined with seat or table-like elements. Including the adolescents in the design of children’s places, asking them what obstacles they face, what observations they have, what type of activities and places they would prefer, will give designers and policy-makers valuable insight for creating a truly inclusive neighbourhood for people of all ages.

Most important are the diamonds within the triangle, the pieces of ‘free’ land, undefined open spots, where kids can create their own space like empty terrains, small plots of various nature. When these ‘rough edges’ are along the routes – the three orange legs of the triangle – more children will be naturally passing by and the possibility of being attracted to use these spots will increase.

As these places are not specifically designated for children, there is less opportunity for supervision. There are more loose surfaces and natural elements, which increases uncertainty. Do these kind of places attract all children? And if so, are all children across cultures, boys and girls, equally allowed to go there?

The areas designated as places for children give parents a stronger sense of safety and security, because they allow for more natural supervision from parents, teachers, neighbours, or (volunteering) playground professionals. Hence, these places might attract children with less freedom of move. Further research is needed to examine the different use of ‘places for children’ vs ‘children’s places’.

Neighbourhoods with sufficient visibility, well accessible and safe routes for pedestrians/ cyclists offer children more opportunities to play independently in order to develop well socially, physically and emotionally. Routes with some rough edges, undefined spaces, give children and teenagers the chance to create their own children’s places.

Places for children (schoolyards and playgrounds) should offer diverse play opportunities at differentiated level, and rough edges (undefined, natural areas with loose materials).

In order to create a child inclusive neighbourhood, children must be included in the policy, in the planning and the design. The planners and designers should aim for deep understanding of children’s needs, obstacles and desires. Together with children they can plan and design a neighbourhood which is safe and challenging enough to stimulate free play, at places for children and at children’s own ‘children’s Places’.