Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Many East Jerusalem neighbourhoods lack open public spaces, mostly due to the absence of a general urban master plan. A couple of years ago, placemaking initiatives started taking place in the Eastern part of the city where most of the population is Palestinian. It was the first experiment with the concept of placemaking in the entire area. Our challenge was identifying the areas in East Jerusalem that were lacking a master plan and then implementing projects that would turn those spaces into places full of life. The first couple of placemaking projects ended up adding new physical elements to the public space, such as benches, plants, tables, or information boards with text in different languages. It was this issue of calligraphy and languages that proved rather challenging and which prompted us to rethink and refine our methodology for creating inclusive and sustainable places in East Jerusalem.

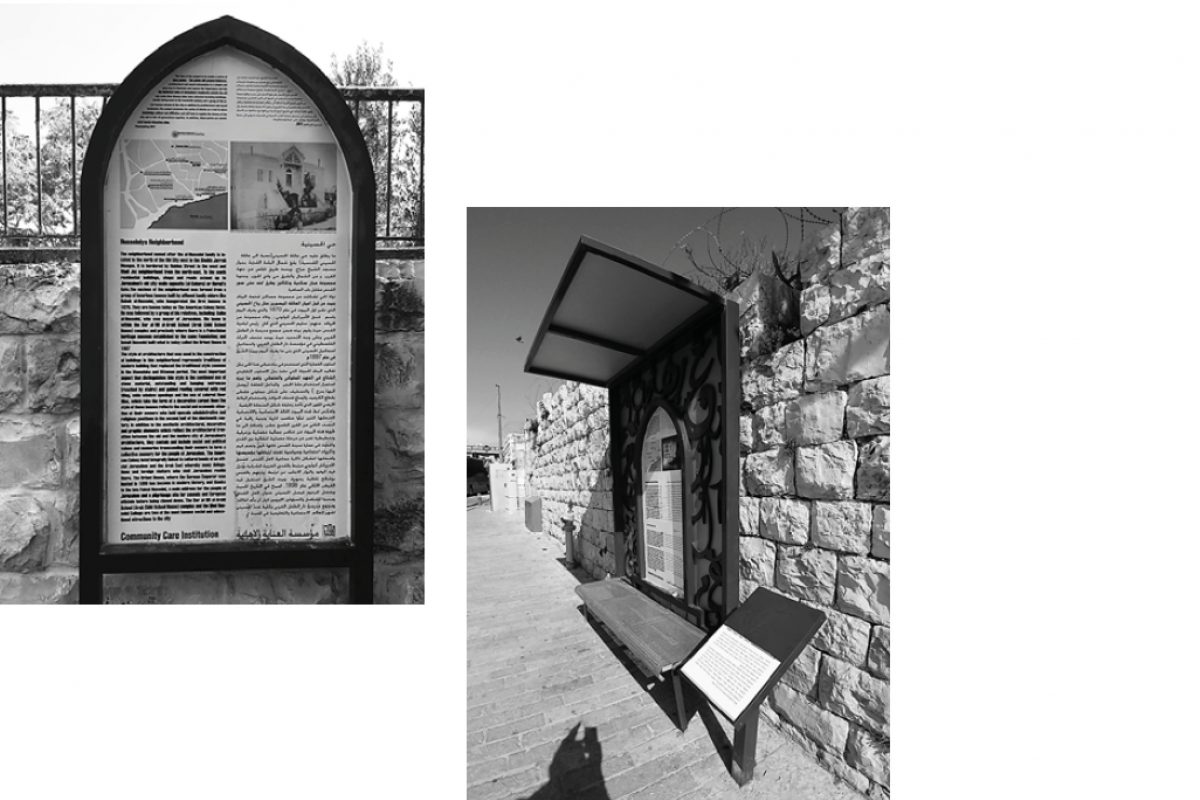

In 2016, the urban clinic at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem led a city-wide placemaking initiative in partnership with the city municipality and the NGO Eden. Guided by a local architect and urban designer, the residents from the area created a special place with corner seating in front of the municipal library of East Jerusalem (see Figure 1) as well as a series of information points. Participants also designed and installed covered bus stops featuring snippets of Palestinian history in Jerusalem (see Figure 2).

In their original design, the projects described above, included some text in English and some in Arabic. After a while, however, one of the information points was vandalized by a group of Israelis living within a Palestinian neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, so the city municipality decided to add another element to the original design, but this time in Hebrew. Shortly afterwards, the info-point was vandalized again most likely because of the new addition (see Figure 3). It became clear that we had to change our methodology and create new tools to address the issue.

In order to document our approach to implementing inclusive, sustainable and applicable placemaking projects in the city of Jerusalem, we created a toolbox that helps placemakers assess a community’s satisfaction and sensitivity toward the proposed interventions. We had to take a closer look at past projects to draw some key lessons and conclusions. Ultimately, the goal of our toolbox is to minimize the risk of vandalism on the one hand, and on the other – to maximize community’s satisfaction with the project, while ensuring its long-term sustainability. Since its creation, the toolbox has been embedded in the whole process of defining, designing and implementing placemaking project with local communities and the main advantage of using it is that it helps prevent political, cultural or religious vandalism to almost 100%.

In the case of East Jerusalem, where our projects were implemented, it was clear that written text in various languages would jeopardize the long-term sustainability of our initiatives. In addition, logos of international organizations, local authorities and NGOs could also put the project at risk of vandalism. The elements of artistic murals would have to be evaluated in terms of community approval and overall satisfaction. For example, in one of our projects we used international artistic patterns and in another we combined painted pictures of the old city without adding any text (see Figure 4).

In East Jerusalem we found that flags, languages, text, and mural portrait are putting projects in high risk. Similarly, we noticed that logos and artistic patterns could be either a high or a medium risk depending on the neighbourhood. We also found that one way to ensure the long-term sustainability of a placemaking project is by linking it to existing small and medium size enterprises such as cafes, restaurants or kiosks (see Figure 5) or to other initiatives involving young people, students, or elderly citizens, which are already taking place in the neighbourhood.

Each city is unique. In the case of East Jerusalem the toolbox helped us identify which elements were favored by the local community and which were likely to cause tension or vandalism. But creating a toolbox that measures a community’s satisfaction with a given project can be helpful in many different urban contexts, especially in the early stages of a design process.