Keep up with our latest news and projects!

This paper examines gentrification as an ongoing process and investigates its consequences on social mix and inclusion. The goal is to unfold and examine the tensions between different groups of residents in Galata neighbourhood, Istanbul, through the lenses of inclusion and exclusion. The paper highlights a number of cultural and political issues in gentrified neighbourhoods, with significant importance placed on the tensions between gentrifiers themselves, how these tensions grow and operate, and how they affect the issue of inclusion (or lack thereof) in the inner city.

Gentrification studies are dominated by theorization and conceptualization from Western Europe and North America (Lees et al., 2016). The term ‘gentrification’ itself was coined in London by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 and was borrowed later in discussions of global gentrification (Atkinson & Bridge, 2005). This article addresses the issue of market-led, or in other words classical, gentrification as an emancipatory and ongoing process that not only creates tension between old and new inhabitants, but also between different groups of gentrifiers. By doing so, the article argues that gentrification not only fails as a policy tool for social mix and inclusion in the inner city, but it also deepens social segregation to the point of stirring up tensions among groups of people that belong to similar social classes.

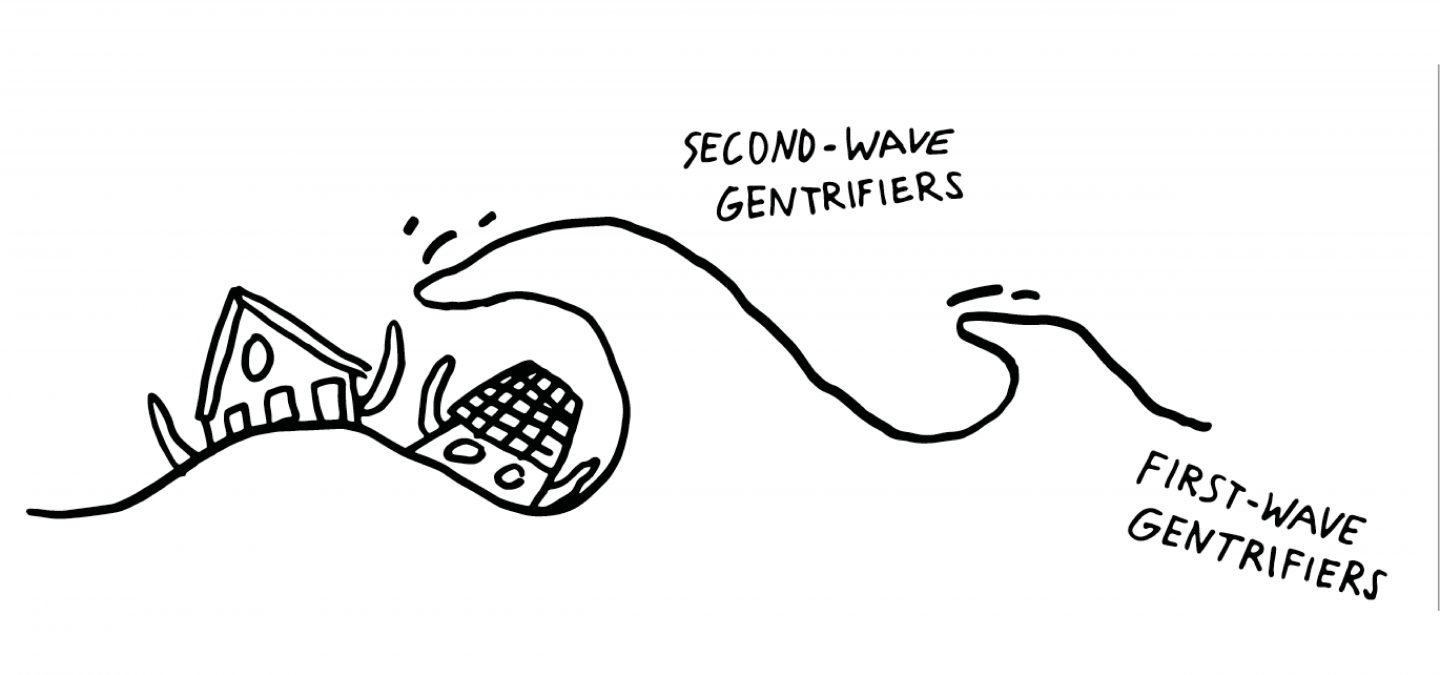

To illustrate this point, I use a neighbourhood from historical Istanbul that has been going through gentrification since the early 1990s. This neighbourhood is called Galata and was part of my PhD research where I analyzed the process of gentrification through interviews with the local government, academics and neighbourhood residents. Gentrification research in Turkey started relatively early, in the 1980s, focusing primarily on historic neighbourhoods in central Istanbul (Islam & Sakizlioglu, 2015). Their gentrification process occurred in private housing markets and it seemed to share many of the same features as classic gentrification in Europe and America. Galata is a strong example of market-led gentrification, and indeed, it received two waves of gentrification, sometimes referred to as ‘super gentrification’. Super-gentrification is another level of gentrification imposed on a previously gentrified neighbourhood by incomers with higher purchasing power than the previous middle-class gentrifiers (Lees & Butler, 2006). It exposes tensions between old and new inhabitants and certain antagonisms between different groups of gentrifiers. This is important, as this level of ‘further’ gentrification and the tensions it causes are understudied in the literature, yet they show how exclusionary the process can become. Although Galata falls into the category of market-led gentrification, the municipality has had a considerable role to play in initiating the process indirectly. I will first briefly discuss social mix, inclusion and social spatial segregation, and then move onto the discussion of Galata and how processes of gentrification created various levels of exclusion in the neighbourhood.

There are two concerns in this section with regard to social mix during gentrification: the first is about residents from different classes sharing the same neighbourhood; and the second is the question of the extent to which such residents mix in practice. In spite of the ongoing debate about whether or not gentrification leads to displacement and social segregation, the process has been supported by policy circles globally (e.g. Urban Renaissance and Housing Renewal Programme in the UK) in the belief that it will lead to socially mixed, ‘more habitable’ neighbourhoods. Gentrification has been associated with the attraction of diversity and social mixing (Lees, 2008), and “is said to be a relief from the sub-cultural sameness and ‘boredom’ of many suburban communities” (Allen, 1984, p. 409-428). However, there is little evidence that gentrification creates socially mixed neighbourhoods. As Rose (2004, p. 280) puts it, there is an “uneasy cohabitation” when it comes to gentrification and social mix. According to many studies on gentrification and social mixing (see Goodchild and Cole, 2001; Atkinson, 2005; Cheshire, 2007; Freeman, 2006; Lees et al., 2008; Rose, 2004; Uitermark et al., 2007), it seems to produce more tension between different classes rather than less.

A gentrification process that results in some or total displacement would typically push working class inhabitants to the periphery. However, these residents tend to maintain most of their work and social connection in the inner city and the city centre (Kesteloot, 2005). This creates many problems for them in the long term, such as further deepening of social and income polarization. As the process of gentrification progresses and reaches the point where the middle class is displaced from the inner parts, ‘bubbles’ of social classes begin to form in the city where no class interacts with another. ‘Bubbles’ refers to working-class people not only losing the chance to socialize and spend time in the city centre, but also losing their jobs in the area and all connections to it. It is not merely that the higher income classes benefit from this process, but that working-class people are not able to access the amenities and jobs that can guarantee them satisfactory standards of living and health. This can cause further demonization of the poor by increasing the economic gap between different social classes, causing a rise in what Butler (2005) calls ‘the urban other’.

From the 19th century Ottoman era to the 1950s, Galata was a middle-class neighbourhood. Its population consisted of mainly Turkish citizens of Armenian, Greek and Jewish origin. These groups formed the merchant class of the Ottoman Empire, but with the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, they started to face suppression. Between the Armenian Genocide in 1915 and the invasion of Cyprus in 1974, many political events pushed them to flee the country.

After the departure of the minorities, Galata and other historical neighbourhoods were abandoned. Housing became very cheap. Many immigrants from the central and eastern part of the country purchased flats and formed another identity in those neighbourhoods. Unfortunately, historical buildings were not well-maintained because of the complicated bureaucratic nature of the conservation law which required legal and architectural assistance that poor residents were unable to afford (Belge, 2002).

However, in the late 1980s, some historical neighbourhoods caught the attention of middle-class intellectuals and artists, who started buying and renovating houses in these areas. Hence, gentrification began, and with the change of inhabitants, local governments started providing better services (more frequent garbage pick-up times and cleaning, giving away planning permissions more easily for a change of function such as cafés or hotels), and the number of hotels, cáfes, designer shops, and art galleries increased dramatically. Recently, Galata has experienced a second wave of gentrification, which consists of people who are financially better off than the first-wave gentrifiers. Now I move on to analyse the dynamic changes which occured with the arrival of second-wave gentrifiers.

Classical gentrification has been an important phenomenon in Istanbul, and it has been caused by some of the same processes observed in the global North. The main elements such as rise in finance and business services, transformation of the economy, rise in the numbers of professional workers and the culture and taste of these professionals have been observed in many cities around the world, and they are also present in Istanbul. In this section, I analyze and interpret this story deeper by looking at four points: relationships between old and new inhabitants, tensions in Galata, indirect state involvement and social inclusion.

The first point is that tensions in gentrified areas are not limited to those between old and new inhabitants. Gentrification creates many levels of tension between different groups and between groups of gentrifiers as well: these are indifference, antagonism, and indirect conflict. In Galata, it is clear from the statements of the working-class residents I interviewed that the local government had essentially ignored them by not providing adequate municipal services. However, my respondents did not realize that, and instead, felt grateful when the first-wave gentrifiers arrived because that is when the Municipality started providing better services. This is one reason why working-class respondents felt no antagonism towards the gentrifiers. However, recently-opened art galleries, cafés and restaurants have certainly made the district much more popular and improved the demand for housing. Yet, old inhabitants are not in the market for designer clothes or vintage bags. This makes them feel excluded, as if they are no longer part of the neighbourhood, which in turn creates tensions between old and new inhabitants. According to first-wave gentrifiers, second-wave gentrifiers demonstrate indifference towards them, and they do not socialize with them in any way. First-wave gentrifiers openly show antagonism and in some cases, seek indirect conflict with second-wave gentrifiers (for example, by calling the police when it is too loud), and they also do not believe second-wave gentrifiers should be living in Galata. Similarly, first-wave gentrifiers show indifference towards the old inhabitants.

People who moved to the district because of its history, architectural beauty and narrow streets that remind them of 19th-century Istanbul or people who like to enjoy exhibitions in nicely-restored buildings that used to belong to the Levantines, generally do not want other higher-income classes moving in only because the district is popular and ‘trendy’. This is an interesting kind of tension that is not commonly emphasized in the literature of gentrification. The complaints of first-wave gentrifiers are mostly directed towards second-wave gentrifiers, because the latter do not exhibit the same desire for cultural significance that pioneer gentrifiers do. According to most of my respondents, including old inhabitants and recent gentrifiers, the housing prices in Galata will only go up. There were some first-wave gentrifiers that stated that Galata is becoming ‘too gentrified’ for their taste and they are thinking about moving to other parts of the city as they believe not only the neighbourhood is getting too expensive but also it is losing the kind of authenticity these gentrifiers were seeking.

I found little evidence of social mixing between the old and new inhabitants. Even though Galata has been gentrified since the early 1990s and most of the old inhabitants have left the neighbourhood because of gentrification, those remaining did not have social interactions with any of the gentrifiers. In the case of Galata, it is clear that it is not only old and new inhabitants who do not mix, but also first and second-wave gentrifiers. Most first-wave gentrifiers said they enjoyed the diversity and sense of community that Galata once had and that this was one of the factors that attracted them to the area. However, they did admit social mix was not a priority when purchasing a property in the neighbourhood. In addition, first-wave gentrifiers were more likely to complain about the old inhabitants as the interview progressed. This suggests that once a neighbourhood starts experiencing gentrification through private housing market, having an association to help navigate the process could be beneficial. There used to be a Galata Association, which is no longer active and which did little to resist gentrification or promote social mixing in the area. However, an association where inhabitants can contribute freely to an increased sense of community and make demands from the local government for better police and municipality services before the area gets mostly gentrified can help manage the process of gentrification in a manner that is less exclusionary. Even so, the workings of the private housing market and the desire to exploit rent gaps cannot be controlled by a group of residents, and this makes it really hard to maintain a socially-mixed neighbourhood in a neo-liberal setting.

Next, I found that although this is not state-led gentrification, but rather one produced by the private housing market, the local municipality played a significant role in promoting the process in the area. In Galata, this happened with planning permissions in favour of construction firms, making it easier for them to build new apartments on heritage sites that do not necessarily fit in the neighbourhood, or by allowing second-rate renovation practices and better municipal services.This contributes partly to the tensions between gentrifiers. On the one hand, some first-wave gentrifiers demand better restoration and urban conservation projects, while on the other hand, second-wave gentrifiers demand more hotels, cafés, bistros and overall, more development in the neighbourhood.

Gentrification is a process that can generally improve a neighbourhood’s physical condition and its place in the private market, but in doing so, does not really take the current inhabitants into account. Gentrifiers create this imaginary sense of neighbourhood and neighbourhood relations that actually help satisfy new consumption habits of the higher-income classes.

Gentrification is not a tool for social mixing in run-down neighbourhoods. Not only because it displaces the low-income people who are the very focus of these policies, but also because these policies ignore the structural inequalities such as access to similar opportunities as middle-class people, decline in tenure security, ability to stay in the gentrified area, and failure to create a community between social classes based on proximity (Davidson, 2008; Newman & Wyly, 2006). Only because different social classes live close to each other does not automatically guarantee a decline in social and income inequalities or high levels of inclusion (Davidson, 2011).

In short, gentrification not only fails to create a more cohesive collective identity, but it also produces tension and segregation between different groups of gentrifiers. It appears that the process only romanticizes the notion of social mix while in reality it creates various types of conflict. As Davidson (2011, p. 5) puts it “gentrification operates in an emancipatory mode” creating further levels of social distance. As a result, different groups are led into conflict with each other and the dream of social mix and inclusion can only be understood as a lure.