Keep up with our latest news and projects!

According to the European Commission, in 2016, 118 million people in the EU-28 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion (calculated using the AROPE indicator). This represents almost a quarter of the European population, even though the number has decreased by 1 million compared to 2015, due to actions taken under the Europe 2020 strategy, which has a key target of reducing this indicator. The states recording the highest number of people living in households at risk of poverty and social exclusion are Bulgaria (40,4%), Romania (38,8%) and Greece (35,6%).

Altogether in Romania, 1.139 census sectors fall within the criteria set for marginalized areas and they are located in the capital and another 264 cities. According to the Atlas of Marginalized Urban Areas, 342.933 people at risk of poverty and social exclusion live in these areas. However, the share of the population living in marginalized census sectors is more than ten times higher in very small towns (<10 000 inhabitants) compared to Bucharest. In 56 cities no marginalized zones are identified, but in five cities, over one third (up to 47%) of the population lives in such zones.

In Romania, I worked with areas which became marginalized over time due to several factors: poor and Roma people being “exiled” from other parts of the city, and residents refusing to fully accept them. Moreover, no development projects have been done in these neighbourhoods for 7 years prior to the implementation of our strategy, leaving some people without water, electricity or heat.

In my experience as an urban planner, there are still some cities, where little attention is given to marginalized communities, to the extent to which nobody from the public administration knows the real scale of the situation (number of people and households, socio-economic status, etc.), or is aware of the last time a project has been carried out there, either by public or private stakeholders. Nowadays, special European funding is available for the development of these areas, but the allocation of money is conditioned on the existence of an integrated local development strategy, like the European CLLD (Community Led Local Development) instrument for example. However, the guidelines provided are general, leaving most of the participatory action in the hands of local administrations.

Therefore, the challenge for us was to use strategic planning as a tool to involve citizens from marginalized neighbourhoods at every step of elaborating a local development strategy, from the project launch to the approval of the final document. People’s opinions were always discussed along with administrative factors, thus creating an inclusive strategic planning process, not just a participatory approach. The process involved different actions which attracted citizens’ interest to the subject: public meetings, games for prioritization of problems or projects, accountability actions within the community – involving both adults and children – and equal treatment workshops. These activities aimed at building trust between citizens and local administration in order to create the most suitable social programmes that ensured public services are relevant for all categories of users – children, youth, unemployed, people with disabilities, elderly citizens, etc.

Involving the disadvantaged community in the strategic planning process makes a big difference when it comes to finding the best possible solution to a problem. Moreover, it can help ensure equal opportunity and sustainable development, while generating social innovation through custom solutions. But for the community, there is one even greater benefit – building trust between them and the public administration and helping citizens learn how to represent themselves through bottom-up approaches.

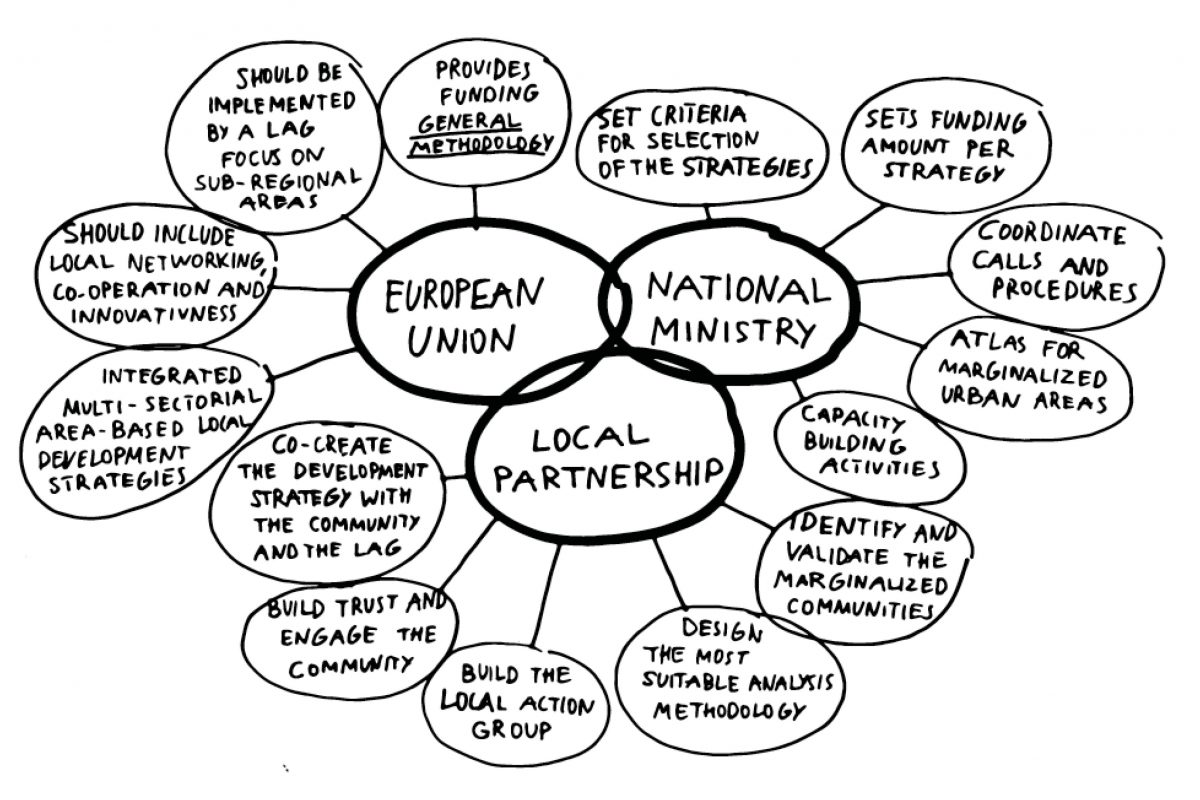

The inclusive strategic planning for disadvantaged communities approach was developed within an existing mechanism created by the European Union, detailed at the national level and implemented by the local partnership.

The European Union provides funding for the CLLD mechanism. It also requires the establishment of a local partnership and imposes the collaborative method. Furthermore, national level actors set criteria for selecting funding strategies and financial allocation, and coordinate the process of submitting and selecting strategies. In some countries, the national public administrations take the responsibility of carrying out studies on employment, housing and social capital such as The Atlas of Marginalized Urban Areas in Romania. However, it is the responsibility of the local partnership to identify and validate the Marginalized Urban Areas, to establish a research methodology, to create a Local Action Group that would implement the strategy, and to find effective ways of involving citizens.

Planning for communities that live in extreme poverty is a process that must be inclusive, given the complexity and specificity of problems that a marginalized urban area experiences. Yet, working with such communities to set development priorities for the next 5 years, for example, is a challenging process, since people’s most burning needs are largely linked to day-to-day survival, and they do not have a general experience or trust in strategic documents, but rather a need for palpable interventions. Thus, the successful implementation of instruments like the CLLD Mechanism could be a good transferable practice that illustrates how local partnership should work to achieve the desired results, given the time, money and social constraints.

Planning for disadvantaged communities means planning with them, because there is no other way to understand how their lives and personal challenges unfold in the specific urban space they inhabit. To ensure appropriate funding and a relevant outcome, a specific strategy for the neighbourhood or area is needed.

We tried to make citizens realize the importance of planning and setting priorities, help them take ownership of the implemented projects and secure their long-term durability. We worked with the classic strategic planning process, which we reshaped in order to be closer and more open to the community. We involved citizens at every step of elaborating a local development strategy, from gathering relevant local data to defining the main goals and the most important projects. We created a partnership for decision-making between local community, municipality, local employers and NGOs – a Local Action Group. By using this inclusive strategic planning process, we managed to get a document done with 80% help from the community.

Below is a structure of the inclusive strategic planning process. Part of it is required by the CLLD Mechanism, and another part is updated from personal experience:

Involvement of local stakeholders

The project started with establishing the Local Action Group and its Directory Committee, which partake in a series of meetings on subjects regarding strategy development. At all times, they are informed about the progress of the process, and they take all decisions by voting, as none of the relevant stakeholder groups (public authorities, NGOs, citizen representatives, private companies) has more than 49% of the votes.

Knowing the community

Next step involved collecting and analyzing enough surveys (statistically representative) that would allow for the identification of marginalized communities as well as people at risk of poverty through AROPE indicator and other socio-economic features of the population.

Familiarizing citizens with the process

Organizing focus groups in different areas, half with people aged 15-29 and half with people aged 30 and over, helped promote the project among residents and identify specific problems within the area. With the assistance of a moderator and a facilitator, participants were working in teams of 5, listing the main problems on a specific topic, like infrastructure, mobility, public services, etc. Each team leader then presented their conclusions to the larger audience, prompting a broader discussion.

Building trust and identifying the catalysts for urban regeneration

This was done by organizing a series of events in the community aimed at building trust, among both children and adults: chalk drawings on the pavement, greening, little citizen questionnaire, photovoice activities, etc. Such events help identify local leaders, who can later on make valuable contributions to solving the problems of the community they live in.

It was also helpful to look for potential activities that the community has a special talent for, like sports, or music, or arts and crafts, since they can be leveraged to generate urban and social regeneration.

This is how we learned that in one city, when kids couldn’t afford to go to school, they were training in Greco-Roman wrestling, under the supervision of a local leader. They were motivated by the career they could make in sports. Two of the trainer’s sons, young boys who live in the very same community, are currently European and world champions. Their success inspired the rest of the kids.

Helping citizens work together and represent themselves

One of the most important actions is getting citizens to work alongside experts in proposing projects that best respond to their needs, and helping them understand the benefits of the integrated approach.

Given the limited funding, another crucial action is getting citizens to prioritize the projects. This helps them understand that the municipality cannot solve all their problems at once and that the regeneration of their neighbourhood is a slow process which cannot happen without them. Moreover, they have a responsibility of following up and getting involved in the implementation.

Involvement of the citizens in the creation and implementation of the strategy

Conducting public debates on topics such as: strategy area delimitation, identifying problems, proposing solutions, prioritizing interventions and last but not least – agreeing on the final content of the strategy ensures a constant involvement of the citizens throughout the whole strategic planning process.

In order to get valuable input on the strategy content and help people understand the process prior to implementing projects, each meeting should engage citizens in a different game such as drawing on maps, writing strengths and weaknesses on colored papers and displaying them in front of the others, voting with stickers, engaging in discussions, etc.

The inclusive strategic planning process was constantly supported by experts and facilitators who reminded the population that integrated interventions should also be designed to combat segregation, social exclusion and to ensure equal opportunity for all citizens. Special attention has been paid to interventions that ensure the participation of children in education such as combating the effects of social exclusion within the educational process.

Being involved in the strategic planning of their neighbourhood shifted the perspective of the local community: while at first Roma and non-Roma people were unwilling to even share the same room, at the end, upon realizing their common struggles, most of them were working together for the betterment of their lives. Moreover, the local public administration was now fully aware of the problems that these neighbourhoods faced and felt proud to have developed such a project.

As a result, the Local Action Group laid down an integrated package of interventions, both soft and hard. It will receive 7 million euros of European funding to provide quality public services to all inhabitants of the selected territory and to establish social programmes that ensure the relevance of these services for all categories of users – children, youth, unemployed, persons with disabilities, elderly citizens, etc. These projects will be implemented and monitored from 2019 to 2023 (the end of the current European funding period). Hopefully, in the next financing period (2021 – 2027), the European Commission will take into consideration the need to support the continuity of such projects.

Approach elaborated as part of the project “Developing the Integrated Local Development Strategy of the Disadvantaged Community in Bacau Municipality” based on the CLLD instrument Community Led Local Development).