Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Today, we see more and more interest in using placemaking as a tool for real estate and area development. In this section you will find several examples of developers, investors and property owners engaging in placemaking because they see it as an investment, not a cost. The examples of Gamuda, Swire, Lendlease and Publika all reflect models that look at long term value. This also means engaging placemakers from the start, not only at the end of the development, and shifting from ‘placemaking’ to ‘placekeeping’.

In these case studies, the focus is not only on the buildings, but on its uses, activities and experiences too. The combination of ‘hardware’ and ‘software’ is key in their design, and dwell time is a primary objective. For the revived shopping mall Publika in Malaysia, the main drivers are art, a mix of ‘fast and slow places’ (‘fast’ are the places for fast shopping, ‘slow’ the ones where people linger), and a great diversity of incubators and start-ups.

They are forerunners in their field, but as Cistri is noticing, placemaking is mentioned more and more at property conferences, and Gamuda Land saw their approach followed by developers active in the adjacent areas.

At the same time, the case of Hongdae shows how governments can take an active role to stimulate place-led development, also by single private owners. Regulations have a major impact on using the pressure on development for the benefit of better public spaces, turning fenced-off streets into human-centred places with active ground floors.

An example of a place-led development project designed around healthy urban living that STIPO was involved in: the Beurskwartier in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

An example of a place-led development project designed around healthy urban living that STIPO was involved in: the Beurskwartier in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

If we look at the larger Asian and international context, we see that when a new development needs to be put on the map, placemaking sparks the creativity and activates the place with temporary use. But unlike the good practices noted in this section, too often, when the area has become well-known and ready for development, the placemakers are kindly asked to leave. Now, the ‘real citymaking’ begins.

The best practices show that placemaking can bring much more to citymaking. Over the last 50 years, a deep body of knowledge has developed around placemaking on the mysteries of how to create ‘great places’. It teaches us how to turn sterile spaces and areas into places that really serve as the heart of a community; where people want to linger, where a great diversity of users interact and feel at home.

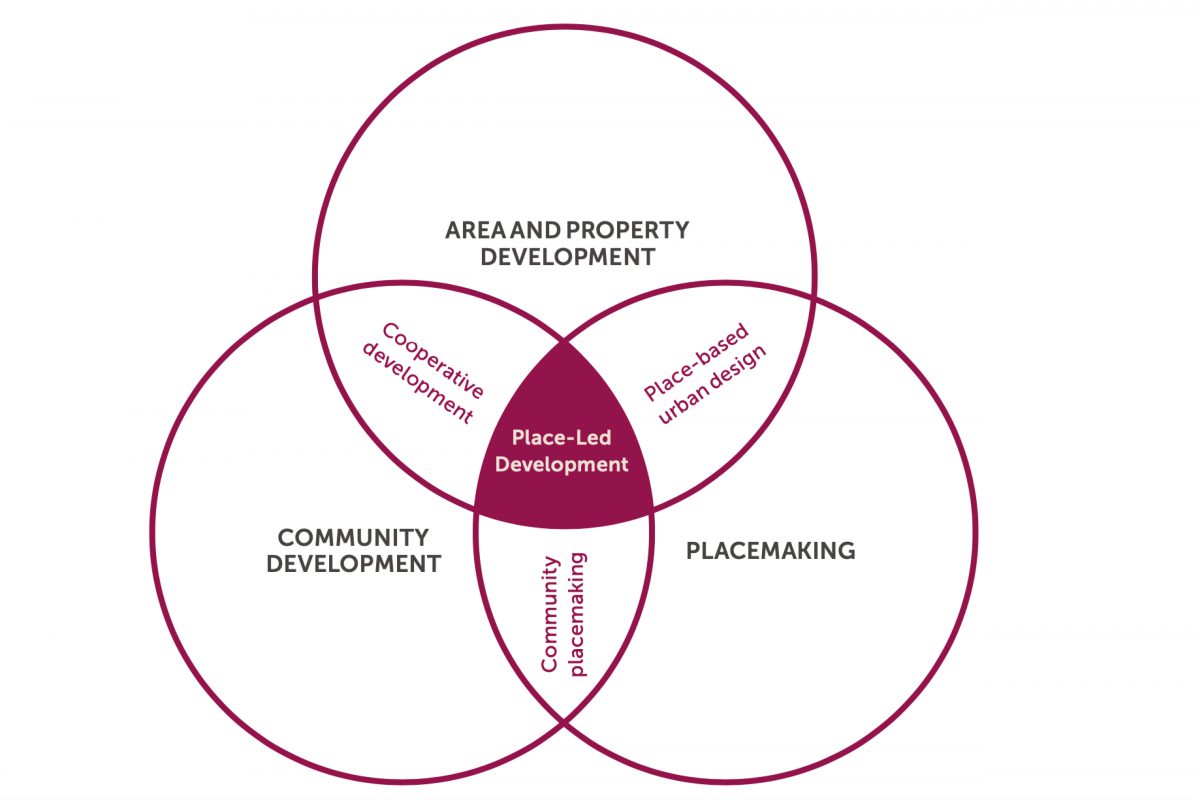

This is where ‘place-led development’ comes in: taking the principles of place, human scale, social life and the city at eye level and using them as a fundament for the entire real estate or area development. After all, we don’t only want great places at the start of the project, but also in the new part of the city that is being developed in the long term.

Place-led development is doing development differently. It includes the integrated design of public spaces and buildings around the values of human scale, the active programming of public spaces with daily use and of ground floor units to feed the public spaces with social life, and the engagement of a varied community of users. Furthermore, these principles are maintained throughout the entire development process. From the first concept and design, to the development, and even to the management in the years and decades after the initial delivery of buildings. After all, great places take years to create; placemaking is an iterative process of constant testing and improvement. With the community’s needs ever-changing, in placemaking you’re never done — as is shown in the best practices in this section.

In short, place-led development is the full integration of citymaking, placemaking and community development.

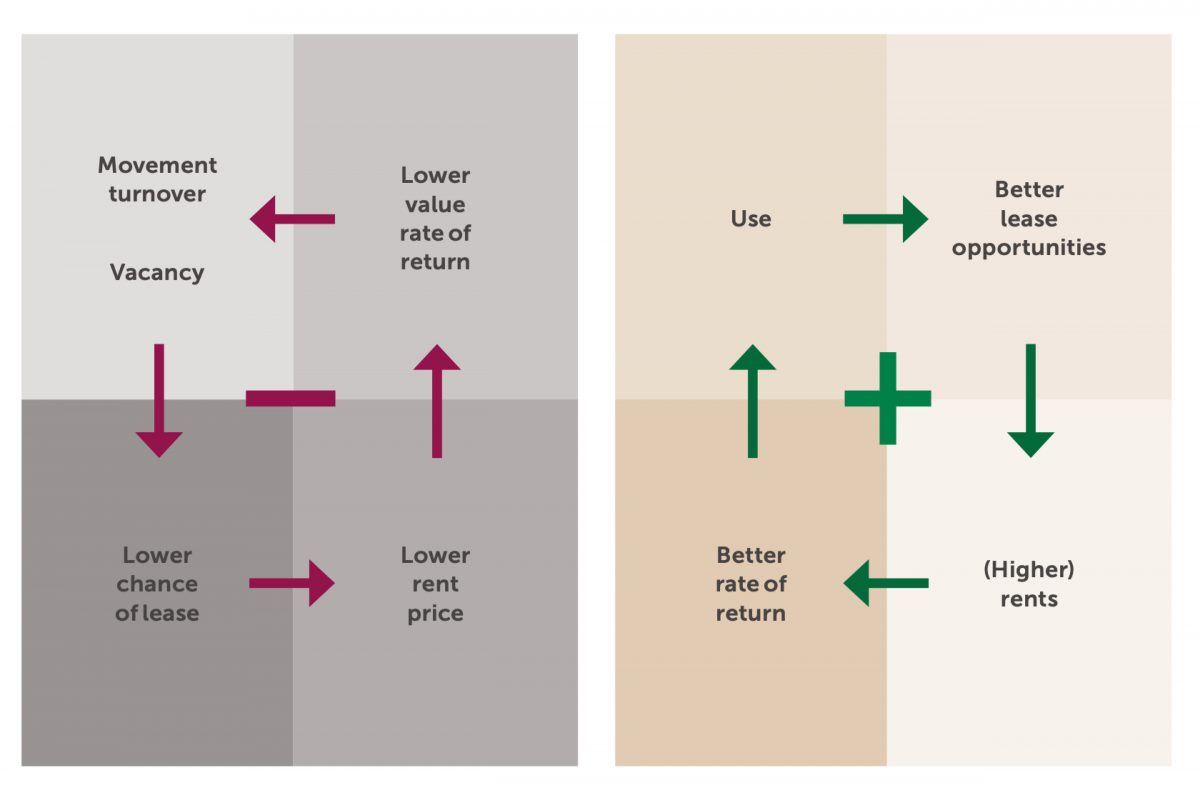

When property loses life, it loses value. But it also works the other way around- bringing new life to existing property through placemaking will increase value.

When property loses life, it loses value. But it also works the other way around- bringing new life to existing property through placemaking will increase value.

Defining place-led development.

Defining place-led development.

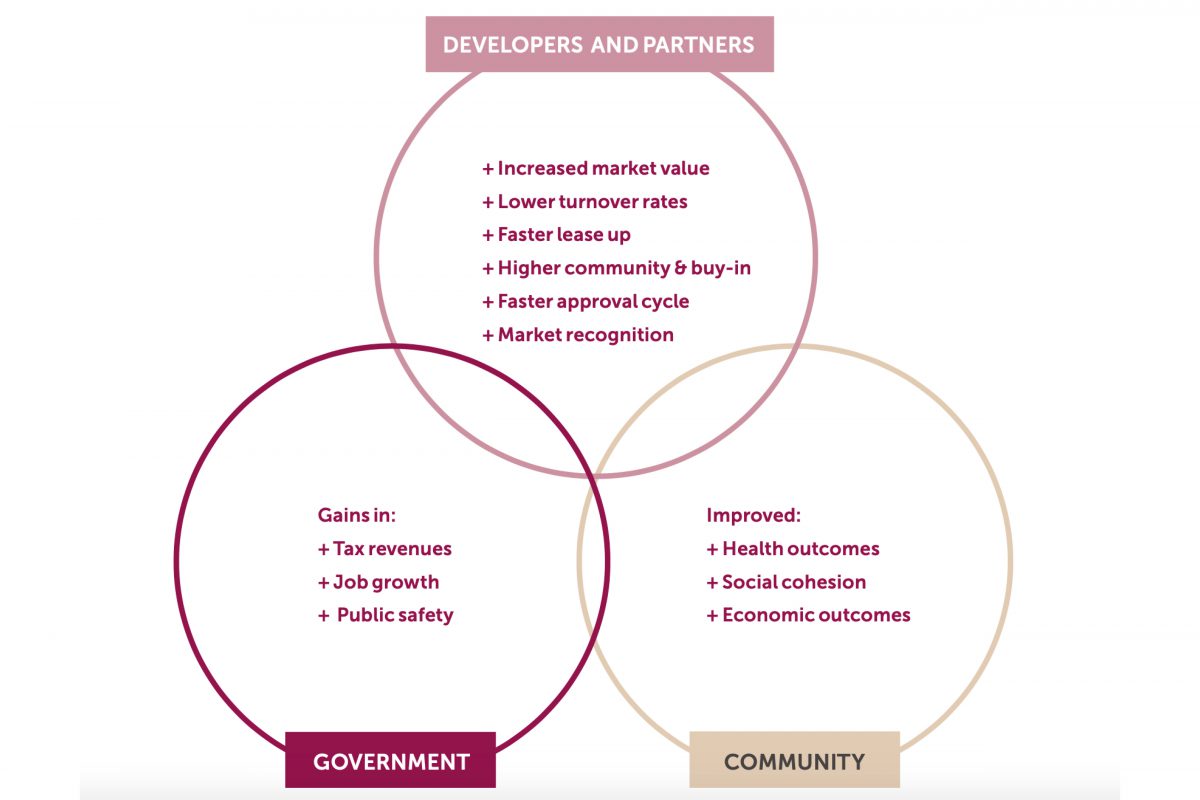

Place-Led Development builds multiple values:

Place-led development builds multiple values.

Place-led development builds multiple values.

A survey by the Urban Land Institute (ULI) shows the benefits that different stakeholders see in placemaking.

A survey by the Urban Land Institute (ULI) shows the benefits that different stakeholders see in placemaking.

If we have all this knowledge, and if place-led development truly brings so much value, why does it not happen more often? Unfortunately, even though the momentum has changed in terms of policy and the international agenda, there are many mechanisms in area development that currently work against the practice. In order to embed placemaking and community-building more into the process of area development, it is important to be aware of these mechanisms, so that we can address them strategically:

In the short term, it is cheaper to construct indoor parking on the ground floor, rather than under- ground. However, this kills the public space for the next decades.

In the short term, it is cheaper to construct indoor parking on the ground floor, rather than under- ground. However, this kills the public space for the next decades.

International capital investment tends to lead to sterile development that is the same everywhere.

International capital investment tends to lead to sterile development that is the same everywhere.

4. Standardisation of construction work. With labour costs for construction rising, we are seeing a growing use of prefabricated façades that are made in factories. On top of this, we see more international capital investing in real estate development, which can lead to safe ‘tick-the-box’ type investments that are similar everywhere.

5. Top-down planning leads to a lack of (mental) ownership. Having only professionals designing an area is not acknowledging the expertise of the local communities that live, work or enjoy moments there.

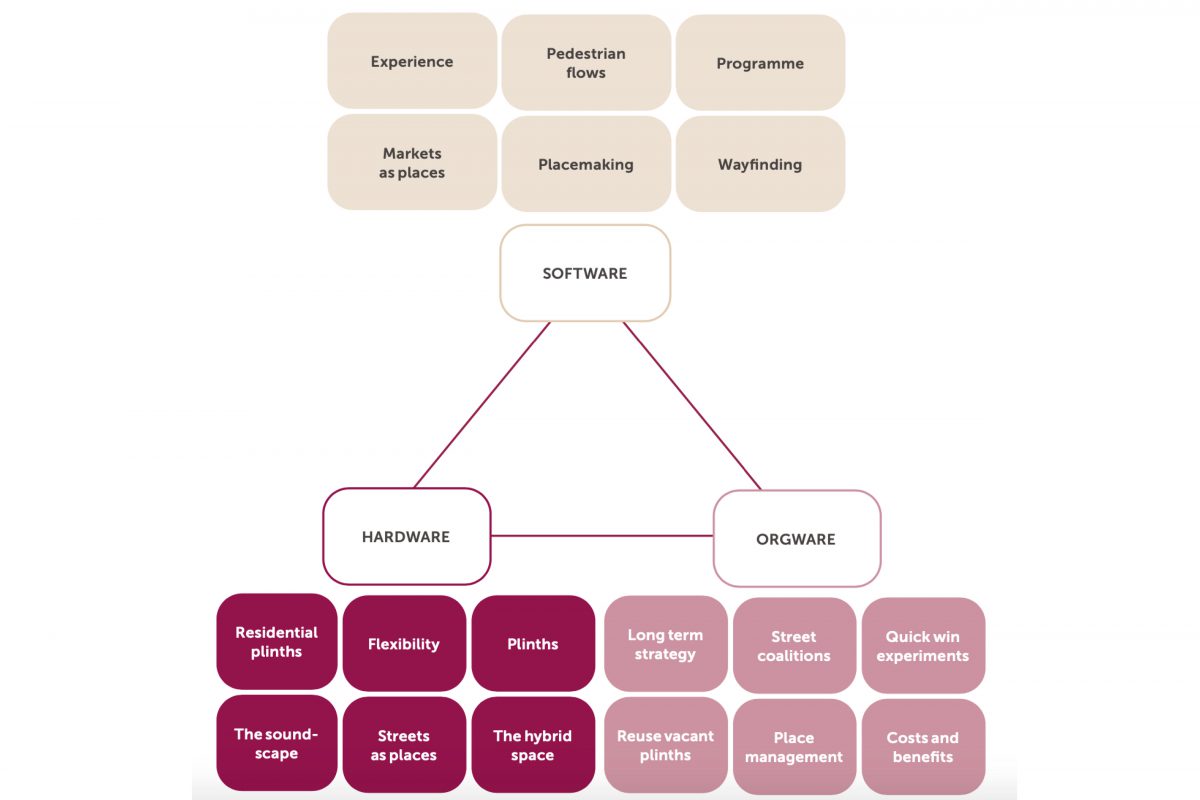

6. Lack of proper management for good places. Creating good places is not only about the built environment (hardware), but it is also about understanding and fostering diversified uses of a space (software) and organising its management with the proper coalition of actors (orgware). So, it is not only about ‘place-making’, but also very much about ‘place-management’, or ‘place-keeping’ as Swire calls it.

7. Designs being made from the bird’s eye view, without paying attention to the street. Too often, we see projects take the bird’s eye perspective — which is important to oversee the context — but they fail to include the perspective of the future users on the streets, sidewalks and squares, thus forgetting people’s perception and experience of a place.

8. Area development is thought of in silos. The fabric of the city is not only fragmented because its different functions are not well-connected, but also because its main stakeholders are not integrated in a common creative process. The process of placemaking can help to bring these worlds together.

How can we address these mechanisms? We see three key strategies emerge.

1: Approach Your Area from the Eye Level

Very often, when we say ‘public space’, we mean the horizontal space that the city owns. However, when we walk down the street, we look around us and have a three-dimensional, not two-dimensional experience. This three-dimensional environment includes buildings, their façades and everything that can be seen at eye level. Ground floors can be seen as a part of public space: the city at eye level. The ground floor may be only 20% of a building, but it determines 80% of the building’s contribution to the experience of the environment. Research shows that if the destination is safe, clean, relaxed and easily understood, and if visitors can wander around with their expectations met or exceeded, these visitors will remain three times longer and spend more money than in an unfriendly and confusing structure.

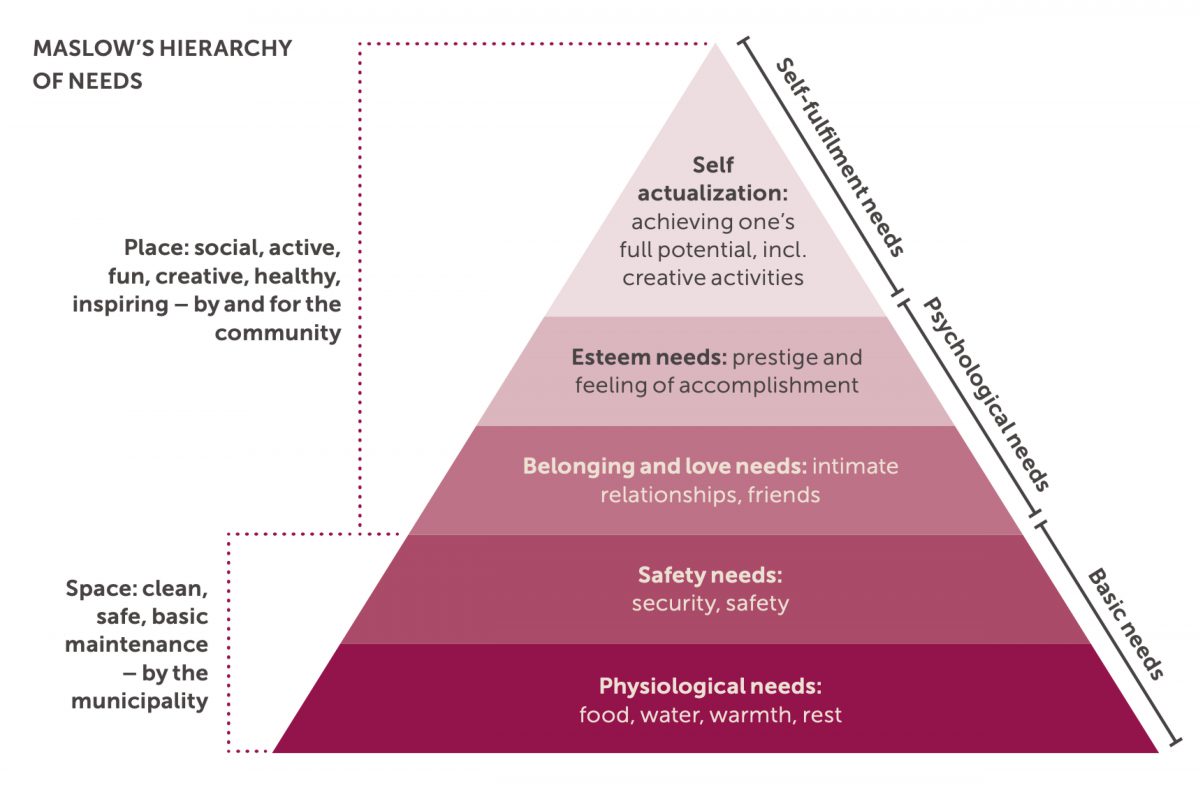

2: Climb in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow developed a classification system to demonstrate the universal needs of human beings. To move upwards in the pyramid, it is necessary to satisfy the needs of the lower levels first. In the light of place-led development, the same principles apply. The city is often seen as the primary steward of public space. They will make sure the public space is clean, safe and has basic maintenance. This only offers the fundamental layers of Maslow’s pyramid. For a functional ‘space’ to turn into an attractive and welcoming ‘place’, co-creation with the community is needed. Cities and main area development stakeholders have an important role to play in co-creating qualitative public spaces to then help the local communities take ownership of the place.

When a public space is clean, safe and maintained, it does not mean it is a place yet. Creating places requires co-creation with the community.

When a public space is clean, safe and maintained, it does not mean it is a place yet. Creating places requires co-creation with the community.

3: Combine Software, Hardware and Orgware

New or existing, street or city, shopping or residential; however different these situations are, creating a great city at eye level is always dependent on the triangle of use (software), built environment (hardware) and coalitions, strategies and tools (orgware). The case of Gamuda land is a good example of how to do this at the level of an entire area development.

To create great places, the development needs to include both its uses and activities (software), human-scaled design (hardware) and programming (orgware).

To create great places, the development needs to include both its uses and activities (software), human-scaled design (hardware) and programming (orgware).

In terms of area development, placemaking is important not only in the planning and the development phase, but during the management phase as well. Measuring impact is a crucial part of this ‘place management’ or ‘place keeping’. Cistri shows a wonderful set of standards to measure these values with. In the end, it is tools like these that are needed to develop great places, and to keep learning and gaining new insights in the process.