Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Tradition has betrayed us. Cities have left their fate to city experts for too long. This practice was firmly established during the 1920s, and eloquently synthesized in Le Corbusier´s idea that says the design of cities was too important to be left to the citizens (Hall 1988). Since then, cities have been designed without the concern and participation of their inhabitants. The result – huge gaps of social content in the city, streets abandoned by people and conquered by cars, all of which contributes to the breakdown of urban social life and communities.

However, it seems like a paradigm shift is underway. Cities are developing and implementing new methods that involve citizens in the creation of urban spaces, but more radically, emphasis has been put on participation throughout the entire process: from the generation of ideas, through design all the way to implementation. Yet, the city’s government institutions are still not flexible enough to deliver this task to the neighbours, so participation remains exclusive in some aspects. Moreover, in this logic of urban development, dictated by expertise over experience, people’s right to participation seems forgotten or neglected.

The methodology presented in this article highlights tactics and strategies of Playful Actions that allow people to make decisions about their cities, while also inspiring greater interest through inclusive recreational actions in the public space.

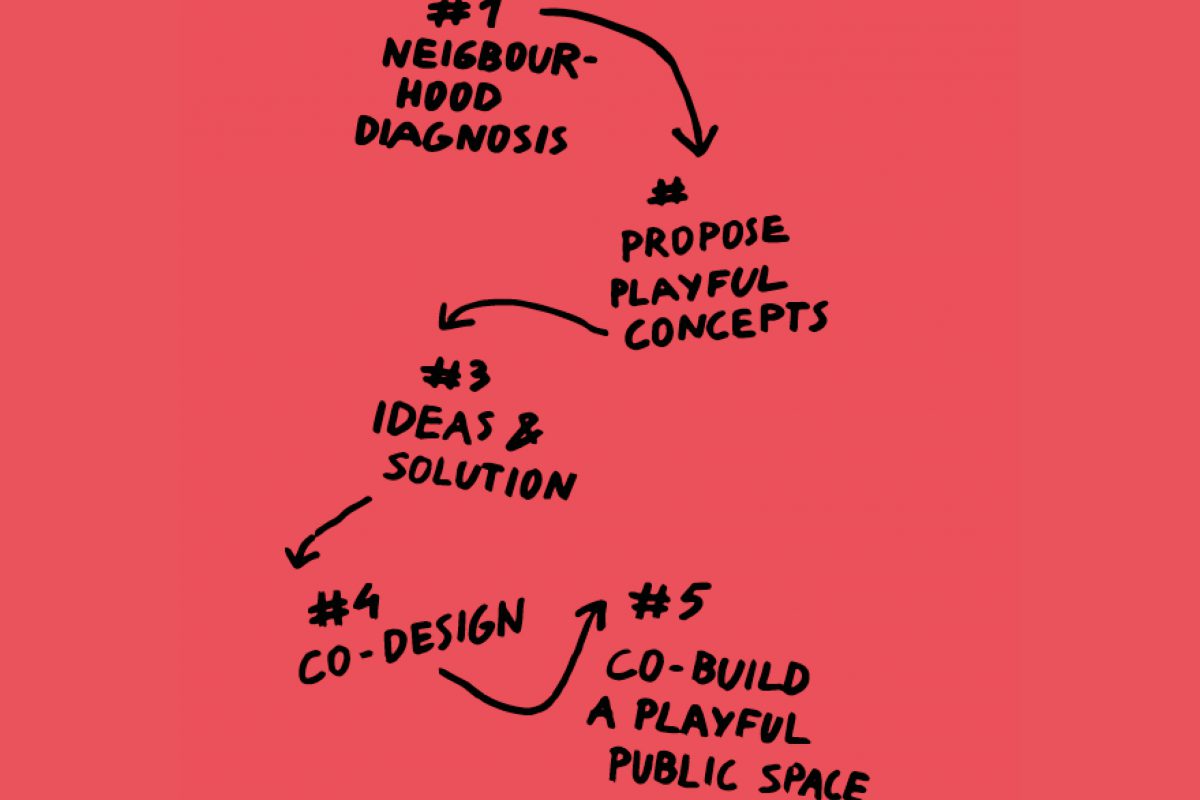

Playful Neighbourhood is a socio-territorial intervention programme based on a collaborative urban design approach. It is structured in five intervention phases (1 per month) in 3 impact dimensions (social, territorial and network community). During this process, playful participatory and community-based actions are carried out to engage the neighbours in the use of tactical methods for urban planning, ending with the execution of a shared community project.

This process of collaborative urban design is facilitated by urbanists and sociologists, but ultimately design decisions are taken by the community1, which is seen as the main connoisseur and beneficiary of its territory (Sanoff, 2000). This approach compels the facilitating team to use operational methods with neighbours. Such methods are designed to provide a deep understanding of local social and territorial dynamics and to identify difficulties, problems and desires. Hence, the facilitating team can evaluate the neighbourhood potential from the perspective of its inhabitants and engage them dynamically and actively in the process.

The construction of neighbourhood projects move from the conception of space to ‘place’ (Augé, 2001) through the active participation of the people linked to this space “making” (PPS. (s.f.)). The process of becoming a ‘place’ represents a deep resignifying of the territory as much as a spatial transformation, with multiple positive consequences for its beneficiaries. The responsibilities and rights, political, social and civil, of individuals are emphasized throughout the entire project in a given territory (Velasco, 2005), specifying the need for active participation from the local community.

The focus on collaboration plays an important role in the reconstruction of ‘place’. The sum of concrete actions to transform the shared space of a neighbourhood builds in the collective imagination of the community a kind of symbolic resignifying, which stimulates new affective relationships between people and place (Berroeta & Rodriguez, 2010; Sen 2000). Furthermore, the physical transformation associated with the aesthetic image of a space has a transforming effect on individuals’ perception of the city (Lynch, 1960). This is why short-term intervention initiatives, popularly called today tactical urbanism (Lydon & García, 2015), can turn into significant transformations in the long term.

In this context, playfulness as a strategy becomes relevant. Its characteristics allow us to promote the active and unprejudiced participation of the community in the place, stimulating their creativity and drawing ideas from their local experience (Brown, 2009). Moreover, humor can also transform the collective conception of place; it can be used as an effective urban tactic in placemaking.

Play has been present in societies, both human and animal, since forever. In fact, it could be considered an intrinsic element. Johan Huizinga (1949), in his book “Homo Ludenz”, studies the elements of game and its effect on culture. He demonstrates that playing is natural for people, extending the concept to various acts that have to do with recreation and dispersion, and that play is transversal to different age groups.

In addition, game has always been practiced, as a way to use imagination and emotions to face the daily challenges and reality without the limits of common logic. Thus, game allows those who participate to leave the common canons and create places outside of the box. Games allow things to be arranged in a different way, to generate new meanings, converting the ordinary into extraordinary.

Game also allows people to transmit positive ideas to those who share the playful action and toward the place where the action is carried out, thus supporting the process of resignifying in highly stigmatized spaces.

As Dr. Stuart Brown says, “Play is more than just fun”.

The Playful Neighbourhood Programme is based on a scalable and progressive process. It will be explained through two cases: one developed in Valparaiso in 2017 and an ongoing one happening in Montevideo, Uruguay. Both cases were designed based on the same methodology, even though they show tactical variations due to differences in contexts and objectives.

Playful Action #1: Neighbourhood diagnosis

Its objective is to understand the collective sense of the neighbourhood, trying to comprehend the territory using the neighbours’ knowledge. The results should indicate relevant themes and concerns of the community. The action should, thus, serve as an orientation point that helps us adjust the process towards addressing those issues.

Playful Action #2: Projection

This action captures different possibilities and dreams of transformation and improvement that the inhabitants envision for their neighbourhood. The expectation is that this stage will inspires broad imaginative ideas and dreams that can indicate new possible urban situations without placing any limits.

Playful Action #3: Test of concepts and ideas

This stage attempts to transform a top-down design into a bottom-up process. It allows residents to review existing design concepts and ideas and modify them if necessary.

Playful Action #4: Co-Design and prototyping

In order to put into practice the dreams and ideas for the territory gathered in action #1 and #2, the 4th action calls on the neighbours to participate in a workshop and create specific design possibilities for a particular space in the neighbourhood. This action is expected to promote collective planning and design, introducing specific interventions in the chosen area, in common agreement among neighbours.

Playful Action #5: Implementation

This action encompasses the construction of the collective space. It is the final part in which all neighbourhoods take part in building the collective project. The main idea is to create places with local identity, which have a deep significance for the residents of the neighbourhoods.

The Playful method allowed active and equal citizen participation on a collective project, showing a significant trend towards citizen involvement in public space, as well on collective issues that are affecting the neighbourhood, mainly happening after the implementation of Ludobarrio. This change of behaviour can be assumed to be the result of the engagement process between neighbours and local government, that Ludobarrio enhance through the playful actions.

The community is more empowered, active and linked as a result of methods or tactics designed to engage an important number of people through a construction process by stages. Moreover, playful actions establish trust between different local actors, forming strong groups to achieve the final spatial transformation project as well as subsequent negotiations in the territory. Therefore, territories where Playful Neighbourhood has been implemented, have demonstrated strong appropriations of the space in question, giving the place a new meaning, and where a strong group of participants are involved in its maintenance and sustainability applying for additional funds to improve the place now from their own and collective motivation.

Reinforcing participation might be the most relevant result of this methodology, in which the physical transformation of a public space is accompanied by strong capacity-building for the entire community. It is clear that playful actions enhance and accelerate the collective spirit.