Keep up with our latest news and projects!

A museum has many tasks, among those are: collecting and conserving cultural heritage, disseminating knowledge via exhibitions and publications, and being a focal point for visitors. The City Museum of Stockholm, part of the municipal City of Stockholm, has an operational area of over 188 square kilometers which encompasses about a million people. Municipalities here are socioeconomically diverse – opportunities and even life expectancy vary across neighbourhoods.

One main objective of Stockholm’s politicians is to stimulate urban integration and social sustainability, defined in terms of personal fulfilment, affinity, security and – by synthesis – well-being. How can the museum contribute to this end?

One way is to ask ourselves who we work for, what form our work takes, how and to whom we present it, and last but not least – where our work takes place. Should the static museum building be our sole arena? We posed these questions in 2016–17 during Östberga, Östberga: the City Museum On Site, a project conducted in the suburb of Östberga.Located immediately south-east of the centre of Stockholm, the area is best described as a divided space: Gamla Östberga, built c.1960 by the HSB building society, consists of 800 privately owned housing-cooperative flats; Östbergahöjden and Östbergabackarna (referred to below as Östbergahöjden) was built a decade later during the Million Programme, a state initiative to build a million new homes in ten years. Here Svenska Bostäder, a municipal housing corporation, built 49 blocks of 1 200 rented flats.

Gamla Östberga and Östbergahöjden are very different in nature. The former is usually associated with the industrial working-class and the latter with criminality, torched cars, and even murder. The latest incident, in the summer of 2017, saw a young man gunned down in the street. Many of the area’s characteristics are typically present in less affluent parts of Stockholm with apparent lack of services and poor public transport. Östbergahöjden is almost an enclave, surrounded by major roads, industrial estates and one major green space.

Although the Museum focused on Östbergahöjden, one of our goals was to actually break down the mental barrier that divides the two neighbourhoods. Another goal was to collect knowledge about life in the area and reinvest it in the inhabitants. We also aimed to spread local information which, although known to the Museum, was relatively new to local residents.

Our methods were cohesive if sometimes unconventional. City walks narrated the area’s one-thousand-year archaeological history; in-depth interviews focused on life in Östberga; summer jobs let young people document their perspective on the neighbourhood; and participatory observation at places such as the parklek playground, preschool and Östberga Community Centre allowed us to collect stories and photographs, and to share our own talents and skills.

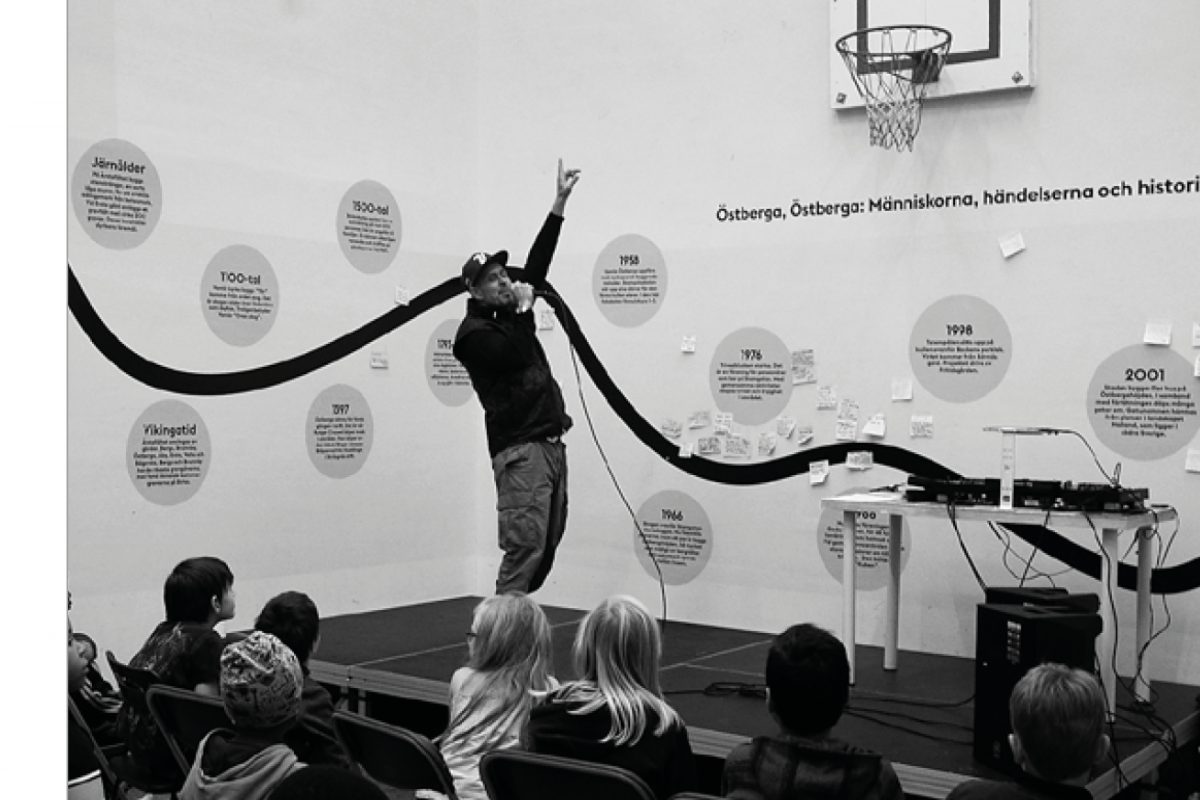

We held narrative cafés, film screening evenings, and handicraft courses. We also produced an interview magazine and an exhibition (and later on a detailed report). The exhibition was held at Östberga Youth Centre, which was also the venue for our talks. Our activities were designed to both give and receive.

Holding the exhibition in Östberga was an obvious, albeit problematic choice. It was important that the exhibition does not come off as patronising or lecturing locals about their home. Yet at the same time we needed exhibition content. The solution was a ‘show, don’t tell’ concept, with elements such as card and memory games, and a huge floor game with giant dice, all conveying information about the local area.

However, the above-mentioned murder impacted the exhibition. The incident took place shortly before the opening, which led to a two-week postponement. Given that the exhibition was open to the public, some were concerned that criminals might turn up.

Certain features were therefore toned down: a photograph of police officers was made smaller and the ‘Welcome’ sign was re-positioned away from the entrance. The importance of the exhibition taking place was reaffirmed by everyone with whom the City Museum came into contact: criminals must not dictate events in Östberga.

Did we manage to contribute to social sustainability? We think so.

Many local inhabitants:

We believe that the Museum’s presence in Östberga helped strengthen self-fulfilment, local affinity and security among people in the area. We know, for example, that our input later contributed to the opening of a local cultural centre. Collective well-being was reinforced, at least in part because we succeeded in stimulating local people’s interest in their home environment.