Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Cities cater to everyone, regardless of lifestyle, religion, culture, wallet size, age, sexual preference or demand for theater, food, sports or greenery. They absorb newcomers, negotiate differences between opposites and create narratives for everyone to relate to. Such is the story we are often told, and of course, it is all true. But at the same time, we must ask ourselves, do the residents of our ever-popular cities continue to feel at home in them? And are the public places within a city really even ours?

It is no secret that cities are booming. They continue to attract the world’s top talent, stimulate the economy, act as innovation hubs, and serve as the cultural melting pots of all nations. With that success comes the need for a better understanding and more adequate strategies to ensure that the mechanisms behind our beloved cities maintain that incredible vitality to welcome all and make them feel right at home.

Many macro developments challenge this ability of absorption and adaptation for both newcomers and the generations before them. Think of the quick turnover of old neighbourhoods to the next urban hotspot, leaving the ‘original’ inhabitants strangers in their own street between hipster ginger tea, gin tonic cafes and designer bakeries. Or the apartment blocks and postal codes that thrive on the coming and going of Airbnb tourists, their anonymity diminishing social cohesion and ownership in the buildings and the overall neighbourhood. And more anonymity, the role big international money – whether from private investors buying second or third homes in the best part of town or from big time developers who not only develop for the highest bidder but also create a new kind of ‘public’ but privately owned space – affects the lives of ordinary citizens daily.

Combine all of this with the large influx of strangers who come to live in our towns, all in a mix of well educated & informally trained, rich & poor, worldly & rural raised, difference in how they entered the country with the title expat, refugee or migrant, we get a potentially toxic mix that severely undermines the city’s potential for absorption and inclusion.

In the personal lives of people these macro developments manifest in all sorts of ways, often widening the already existent gap between different social groups. There is an increasing lack of understanding amongst people in how we experience the city, and how different our experiences are.

As a girl you will think twice about walking outside in the dark, but at a certain age you also no longer enjoy going to the park with your girlfriends. It does not feel safe with all the older boys chilling there, there is no wifi nor nice places to sit. And perhaps your parents and family no longer allow you to be outside without the proper male companion. Research in Scandinavia shows that from the age of 9 the girl-to-boy ratio of kids playing outside suddenly drops from almost 50-50% to 20-80%.

For an elderly citizen public life can become a distant phenomenon: something you look at from your window, but cannot enjoy yourself. Seniors often do not feel brave enough to walk all the way, what if they get tired and there are no places to sit and rest? Clear routing, proper sidewalks, benches every few meters, and the close proximity of house doctors, dentists, daily shops are all prerequisites for their participation in public life. But that is just the basics, what would attract them, make it fun? The next food truck festival, or perhaps something simpler, like playing chess with their old buddies or an old fashioned dance with live music in the park.

Central in these two examples are the questions of mobility and the extent to which you feel at home in your surroundings, in the sense of ownership and being able to claim your right to be there. The topic of mobility is a crucial one. The pace and ease with which people travel through the city, and their ability to move from point A to point B, differs tremendously from one group to the other. For the well educated global city dweller the city, or better the world, feels like their playground whereas many of their neighbours in other parts of town stay confined to the invisible ‘borders’ of their neighborhood. If the cheap supermarket is replaced with a boutique grocery or if the public library closes they do not just take the subway or a bike to find another elsewhere in the city.

Instead they feel that yet again something has been taken away. Living in the city is turning more and more into something for the happy few who can afford it. That is not what cities are about. We need to be inventive here. It is not just about designing the right policies, it is also about new types of ownership, collective financing, local grassroots initiatives. Exactly the things that will also increase the feeling of belonging, provide people with some control over their surroundings and make development truly sustainable.

We sense an urgent search amongst politicians, policy makers, property developers, housing corporations and financial investors to find new approaches to work on inclusion and cities for all. It goes beyond placemaking alone. As urbanists of all sorts, we wish to contribute to this ongoing international debate, raised by UN Habitat and many others – a daily topic and a reality in our work – by offering practical alternatives that create cities where everyone can feel at home.

We also feel a responsibility to collectively learn and develop a better understanding of how we influence inclusion and exclusion in our work. As Maria Adebowale, Placemaking Europe leader and established urbanist in the UK, points out, placemaking is highly political. Every intervention in a square, street, neighbourhood strategy or area development we do has an effect on the public realm. That is of course why we are asked in the first place and for good reasons. But while working, we should be really aware of how our interventions play out, whether they contribute, unwillingly, to alienation and exclusion, and understand what we can do to avoid that.

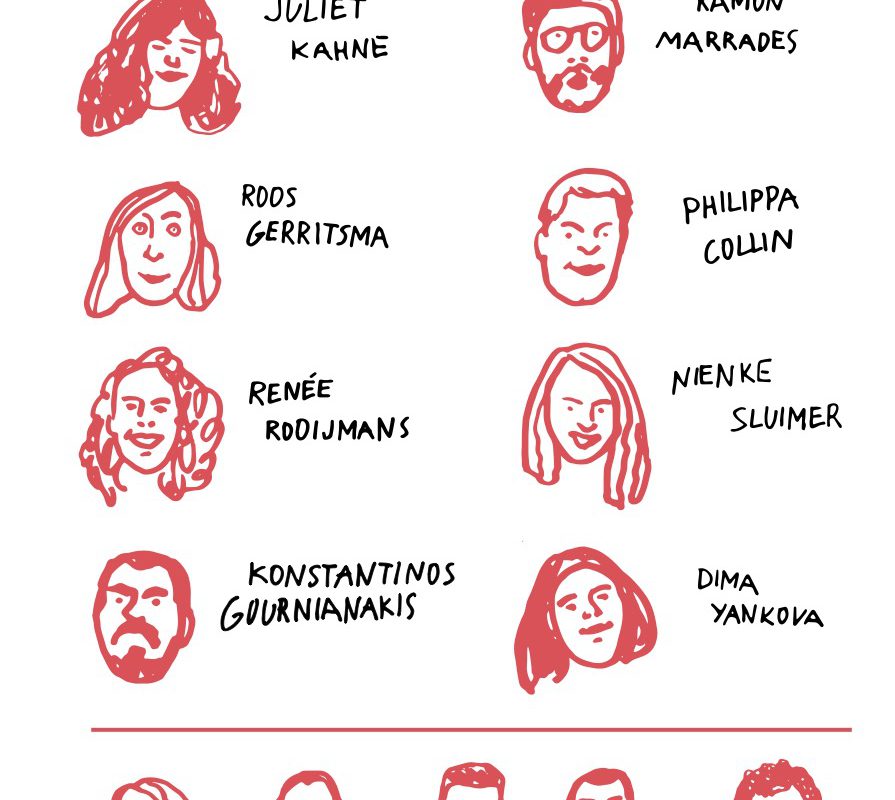

The collective exercise of writing this book, collecting all the case studies, editing and discussing all the materials, gave way to a greater and deeper body of knowledge that we now proudly share with you. We look forward to hearing your thoughts and all upcoming discussions as we are fully aware that this is just the beginning.