Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Large-scale revitalisation projects are not new additions to the global planning landscape. In the modernist era, planners and architects envisioned utopic communities made up of high-and-mid-rise tower blocks within manicured areas of green space. Many of these so-called communities would later come to be described as a “slums”, “ghettos” and all around “failures” with high levels of crime and poverty. Despite having an ideal vision in mind, the actors involved failed to consider the extremely vital social and socio-spatial aspects of envisioning a community. Revitalization has thus come to be necessary not only to refresh crumbling physical infrastructure, but to re-invigorate a sense of meaning and ownership into urban space.

Revitalization is more than the simple replacement of social housing units by defnition. In fact, it represents an opportunity to create attractive, liveable communities by investing in both physical infrastructure and social services, which will improve the quality of life of its residents – and even attract new ones.

This is the case of the Regent Park in Toronto, Canada. When the nation’s largest public housing organization, the TCHC, embarked on an ambitious project to revitalize the crumbling Regent Park community in 2005, it kick-started a campaign in which collaborative planning and placemaking initiatives would be essential tools in reviving the community. Despite being the victim of shortsighted planning and high crime and poverty rates, Regent Park has been characterized by strong political and civic activism, with some of the highest iterations of ethnic diversity and social capital in the city. Regent is now undergoing a 1 billion-dollar state-led revitalization project which will see it transformed into a mixed-use, mixed-income community, while harnessing the collective power of a private-public partnership between the TCHC, three tiers of government, and a major private developer.

©Jack Landau

©Jack Landau

©Jack Landau

©Jack Landau

Collaborative planning practices continue to be an essential tool in revitalization projects such as Regent Park. Although the practice has sometimes been criticized for maintaining unbalanced power relations, collaborative planning still allows for the acknowledgement of unique spatial and social dynamics inherent to a community. Furthermore, it promotes a sense of ownership in the planning and development process, which leads to a well-integrated sense of “home” and self-determination once the project is complete.

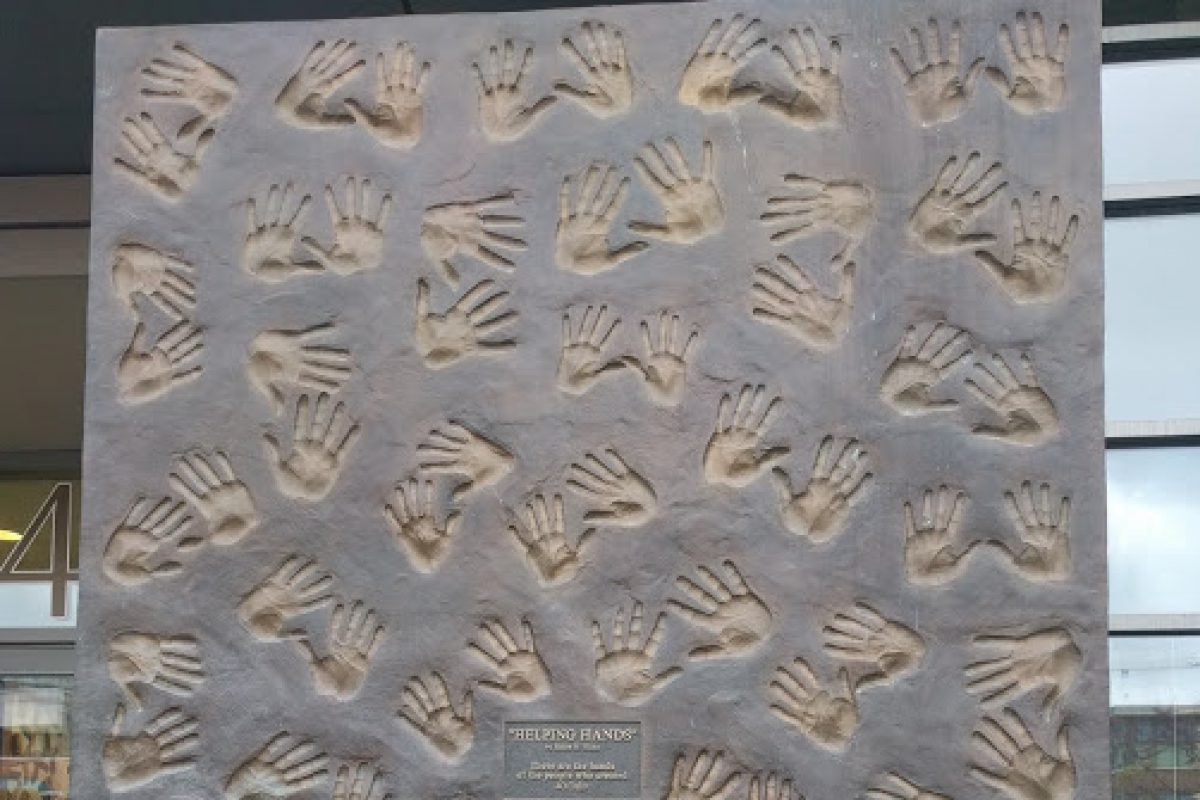

Regent Park’s groundbreaking and resident-led “Social Development Plan” guided all the social goals of the revitalization, in tandem with the economic and design goals of the state and private actors. Its collaborative nature underlined the project’s commitment to meeting residents’ needs and ensuring the community’s vitality even after the revitalization is complete. The plan served as a transformation tool which emphasized social inclusion and innovation as radical and driving factors, and produced 75 recommendations which drove not only the social aspects, but physical aspects of the project as well. This ‘radical inclusivity’ was an essential factor which considered the important interdisciplinary and intercultural aspects of what would eventually become community gardens, public art and programming, multi-faith groups, cultural groups, and the inclusive design of its facilities.

Henri Lefebvre declared that communities have the right to appropriate and claim ownership over their environment. In other words, turning mundane space into a “place” that has meaning, value, and opportunity is everyone’s job. In the context of revitalization, planners can work hand-in-hand with the community and other actors to break down spatial and social barriers, and ensure meaningful ‘places’ are created that can activate a mix of different inhabitants. While planners are at the helm of the ship when it comes to spatial attitudes and interventions, these spaces should be constantly re-animated over time by the communities which use them.

Meaningful ‘meeting’ places can exist in private spaces such as supermarkets and shopping malls, and public spaces such as parks, libraries, and community centres. These can be adapted for markets, arts festivals, pop-up shops, community gardens, sports and recreation, and more. In Regent Park, a completely redeveloped central park and cul-de-sacs redesigned into pedestrianised boulevards offer these opportunities. Furthermore, the acclaimed and state-of-the-art aquatic center, new sports fields, rooftop gardens, and community center all offer programming and amenities for people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds. In the plinth of a new condominium tower is also an arts and cultural hub which houses a café, flexible event spaces, and The Centre for Social Innovation, a non-profit organisation and co-creating hub.

Crucial to these interventions is the fact that these places are equally as flexible and centrally-located as they are animated, with a further focus on cultural neutrality and safety. The intentional goal of making “places” is essential in targeting social cohesion, whether it’s through the design, the programming of the space, or simply the interactions between the citizens themselves.

There has inevitably been some vocal resistance to the practices and outcomes of the Regent Park project, particularly in the capacity of the state and private actors to maintain public interest and avoid gentrification. Nevertheless, Regent Park remains a pinnacle example of the manner in which a collaborative approach to planning with a focus on meaningful placemaking, can actually drive revitalization projects forward in communities where they are truly needed most.

While many other factors come into play in ensuring a successful revitalization, it is the job of planners to consider that their interventions should create meaningful places which allow residents to meet and connect. In collaboration with a network society of actors such as developers, governments, non-profits, residents, artists and engaged city-builders, planners can help mediate the enhancement of a community through a renewed focus on collaboration, place, innovation, and self-governance.