Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Two years ago, the Caribbean region was hit by a number of extremely powerful hurricanes. Hurricane Irma hit the island of Sint Maarten, a former Dutch colony. Immediately after, people in the Netherlands launched Facebook initiatives to collect food, clothing and flashlights to send to the people on Sint Maarten who lost their houses and lacked clean water. On national television citizens were encouraged to donate, but for many this was not enough. They wanted to do more. Facebook groups facilitated the organization of communities that called on others to join in.

By empowering citizens and communities through digital technologies, governments can not only respond to a crisis better or deliver better services in our cities, but they can also make citizens feel more engaged, more responsible and more in control. There are many ways for citizens to participate and contribute to their cities: from a more passive involvement by simply installing a mobile app, by playing a simple game or by voting for a given option, to actively sharing information, measuring or investigating something or evaluating a government policy.

People often feel more at home in their cities when they can help or contribute. Governments are challenged to leverage this willingness and to channel the energy of their inhabitants into constructive and productive activities.

Digital information, data and communication tools together with blockchain and artificial intelligence allow for this collective insight to be gathered. Many tools are already available that create collective intelligence by collecting and synthesizing individual contributions or by dividing large projects into smaller tasks and distributing these among a network of citizens. Unfortunately we see that most attention nowadays goes to smart city infrastructure projects, built and owned by tech companies. Instead of supporting or empowering citizens the distance between them and their environment is widened. Citizens are monitored instead of engaged.

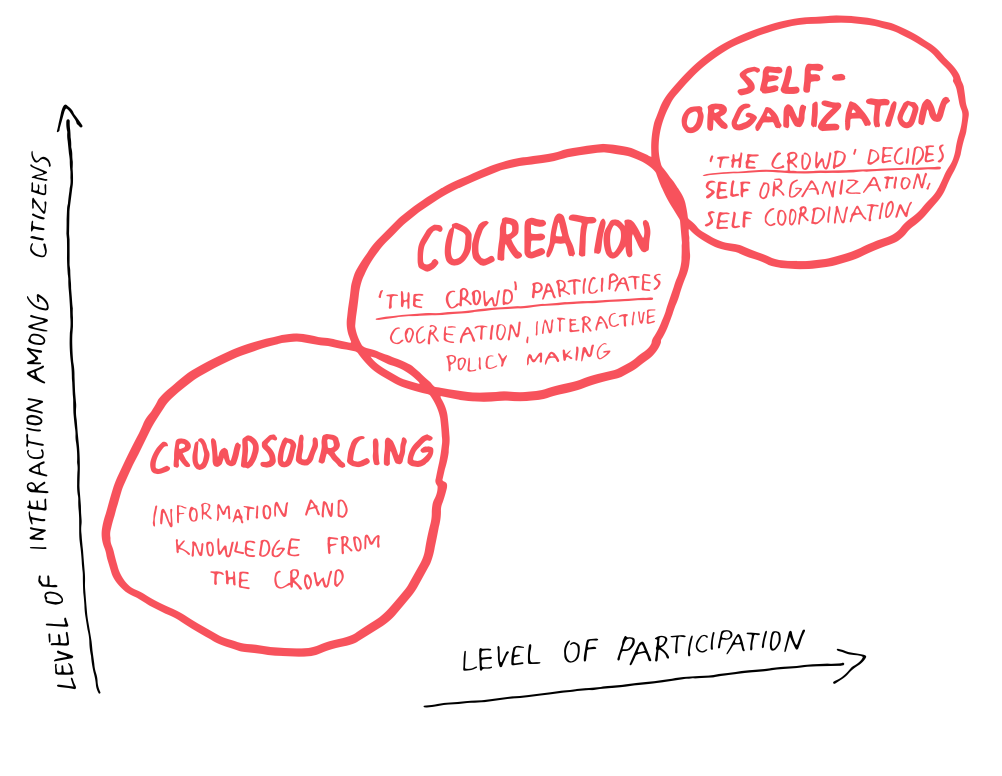

Next to the very important ‘offline’ placemaking, digital technology offers great ways to engage people, give them control and help them organise themselves. In this article I will demonstrate how cities can truly benefit from focussing on these, often simple, existing digital technologies. Hereby I distinguish between three stages of participation: crowdsourcing, co-creation and self-organization.

Crowdsourcing, co-creation and self-organization. Source: author’s personal archive

Crowdsourcing, co-creation and self-organization. Source: author’s personal archive

Crowdsourcing and crowdmapping

One of the most important elements of crowdsourcing is that it enables us to gather a lot of data for a relatively low cost, or no cost at all. Instead of having inspectors check the air quality, the potholes in the streets, dangerous crossroads or broken lights it can now be done by ordinary citizens on their own phones. Where normally the frequency and width of inspections was a matter of financial and thereby often political priorities, with digital technology it is a low cost and potentially very efficient practice that highly increases the quality and service levels of the civic administration, with the help of its citizens. Citizenscan measure everything that happens in the city by simply installing an app on a smartphone, by searching something on the web, by using a hashtag, by sharing the steps of their fitness tracker and by liking posts on social media. This type of technology requires a lot of communication and coordination among citizens. Through the apps, website and social media data is gathered, analysed and processed. www.google.org/flutrends/about

Examples of how crowdsourcing and mapping empowers citizens and local authorities:

Citizens can do more than take (passive) measurements. We see more and more examples of platforms enabling citizens to witness and report. In this way they are actively contributing and collaborating with NGOs, aid organisations and governments. Some of the platforms were developed in response to crisis situations, but have proven equally instrumental in more regular city activities. Examples of citizen reporting:

Ushahidi, mapping in areas lacking basic or trustworthy infrastructures

The open source platform Ushahidi has been used for mapping many large disasters such as the earthquakes in Haiti and Chili and fires in Russia, and also used to map the spread of diseases in certain areas. It was developed by local activists to monitor the elections in Kenya and report the subsequent spread violence throughout the country. After Japan’s tsunami in 2010 the platform helped to map the spread of radioactive radiation from the nuclear power plants that were damaged. People were given sensors to measure the radiation and this was collected and visualized by Ushahidi on the map. Not only people living in the area or country where the disaster took place participated, people worldwide contributed. This provides a rich crisis mapping of an area that is hit by a disaster, such as a hurricane or an earthquake.

Ushahidi combines low tech like sms, telephone calls, emails with smartphones, sensor data and data from official bodies such as governments, firemen, police and aid organizations (Red Cross). The maps give a real time situational awareness, enabling professionals to direct their aid or assistance to areas that are most in need, and providing citizens with practical insights as where to find fresh water, shelter or medical assistance. The platform also gives leverage to citizens posting eye witness reports on local injustices, thereby also enabling them to build their cases and provide international organisations with the proper information to address the national authorities.

Tomnod, identifying and categorising objects massive amounts of images

Similarly, people can also be asked to help out. Over the years people have helped to identify tumor tissue in large database samples, search for deforestation in jungle areas on googlemaps, or in the case of the missing Malasyan Airlines plane people all over the world were asked to help search for the plane on satellite images. The website Tomnod provides people with the satellite images and lets them indicate pictures with a possible wreckage part or light raft. Thousands of people participated in this endeavor. Unfortunately the plane still hasn’t been found. https://www.tomnod.com/

MySociety, enabling local city tools

Of course, even without crisis situations, tools like the ones mentioned above can prove very valuable in daily urban life. In the last ten years the organization mySociety has developed a set of tools that allow people to be active citizens. The tools cover the social values of transparency, community and democracy.

The open source platform is used by governments in many countries. https://www.mysociety.org/

There’s a tremendous amount of experience with the use of these types of apps and data gathering sites throughout Europe, especially in the Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and front runner cities like Barcelona. The technology is out there. It’s just a matter of using it.

Instead of contributing to activities initiated by companies, governments or scientists, citizens can also take the initiative themselves: they create tools, develop products and provide services to each other. We refer to this third stage as self-organization.

Developing new ideas and collective decision-making

There are many tools available that let people work in groups and help them brainstorm new ideas, selecting and evaluating them and making collective decisions. The city of Barcelona has built Decidim Barcelona (‘We Decide’ Barcelona) a website where citizens can participate and take decisions on topics related to the city.

Along these lines, digital platforms that facilitate collaboration among citizens, have fueled the rise of the so-called sharing economy. These platforms provide a marketplace where people can offer services, goods or money to each other. Many cities like Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin and Copenhagen have car and bike sharing and energy sharing initiatives that stimulate innovative mobility and make citizens more resilient.

In the agricultural field, there are active communities of citizens and ProAms (professional amateurs) that work on biology, robotics and the Internet of things for farming applications. It is makers movement around farming. This movement has helped to develop open source tools and affordable techniques that benefit scientists and farmers. http://farmhack.org/tools

Instead of striving for a smart city it might be better to build towards smart citizenship. Smart citizens can make smart decisions, resolve conflicts and take impactful actions. As we have seen they don’t even have to actively participate, their smartphones can do the job for them and provide data that can lead to valuable insights.

The challenge for administrators is to facilitate citizens to contribute in different ways and with different intensities. It is not a matter of simply outsourcing tasks to citizens.

Projects like The City SDK project have shown that it is possible to create a fully-fledged platform through which citizens and businesses can develop applications and services for the city. The platform ensures that the various technologies and data, such as mobility, energy and buildings, are integrated with each other. This is an alternative to the offerings of commercial providers but its principles could also be incorporated more into the commercial smart cities using more open source software and applications. www.citysdk.eu

In an environment of collaboration, citizens are not only much more activated, they feel involved, their knowledge is used, their energy and willingness to help in deployed positively. Moreover, by giving back information they become wiser.

Active committed citizens are desperately needed in times of major transitions, such as the energy transition. This transition can only succeed if citizens play an active role and change their behavior. The growing popularity of solar panels on the roofs of houses is a good example of small contributions that citizens make on an ever-increasing scale. Collective street buys and other community initiatives contributed to the fact that now 1 in 8 houses in the Netherlands is equipped with solar panels.

So, let us not complain about the increasing power of tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon, but ensure that the operating systems of the cities of the future are in the hands of citizens and administrators. Let’s have smart citizens make our cities smart.