Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Our urban environment could be seen as the illustration of a book: it helps to explain all the stories and experiences of the past, shaped by its different users through time. The Time Machine is a tool to travel through time and collect these stories as an inspiration and direction for future place or area development. This article explains how and more importantly, why.

Looking at Dutch cities, we see that many of these stories are being used more and more as a marketing tool for creating one identity to develop an area. Think about Rotterdam as ‘the’ city of contemporary urban development and architecture, Amsterdam as ‘the’ city of the Golden Age and Eindhoven ‘is’ Philips.1 We experience it as the result of a shared sense of connection and past. But in every situation there have been more possibilities where people can relate to than just this specific, chosen story. By reducing these possibilities to one perspective, it can therefore lead to a flat and meaningless image.2 That’s why it’s important to take different perspectives from people in account. Firstly, multiperspectivity in a story is important to increase the awareness that there are (and have been) other people with different views. What’s important for one, does not have to be important for an other. Possible processes of exclusion can thus be prevented. Secondly, multiperspectivity promotes the capacity for self-reflection. Being able to identify and put different perspectives in words deepens knowledge and insights, but also offers insight into the complex reality.3 Riemer Knoop, initiator of Straatwaarden, emphasizes the fact that “there is no such thing as one ‘identity’ of a place, it’s about how people identify themselves with it: the relationship between place and user”. The process of identification and the meaning of a place is constantly changing and must be understood in the context of time. It forms the dynamic soul and sense of place, which gives a place its unique character.

Despite the fact that certain ‘unique’ and ‘historical’ elements are taken in account in urban development, it is noticeable that these elements are not all-encompassing to determine the different ways people actually identify with a place or an area. For instance, elements such as values, emotions, memories and traditions are often not included in development processes.

We live together with many people, who not only share the present less intensively with each other, but also do not necessarily have each other’s past in common.

HESTER DIBBITS (REINWARDT ACADEMIE) AND DANIËLLE KUIJTEN (IMAGINE IC)

With this fact in mind, Dibbits and Kuijten started Emotienetwerken to prevent that “heritage items” will only mean something for a small group. “If only the like-minded are gathered around a heritage item, it is impossible to gain insight in any latent conflicts,” says Jasmijn Rana.4 By mapping different emotions around heritage items, they ensure that these items inspire, enlarge and strengthen new communities. It can mean that people with different feelings change their position towards each other and create new, common values.

In a time of growing cities that are vastly changing and becoming busier with everyday life, we need this vision on stratification more than ever in urban development to maintain the quality of living. Thus, the knowledge about what happened in a building, street, area or city could not only provide inspiration and direction on a material level, but also on a intangible level for the development to a next state. Nevertheless, we see that there is a lack of tools to include these elements in the process to assess and improve the functioning of public space. That’s why the need arose at STIPO to, in collaboration with the Reinwardt Academy in Amsterdam (heritage studies), start researching different methods for bringing the heritage and urban development worlds closer together, which resulted in the Time Machine.

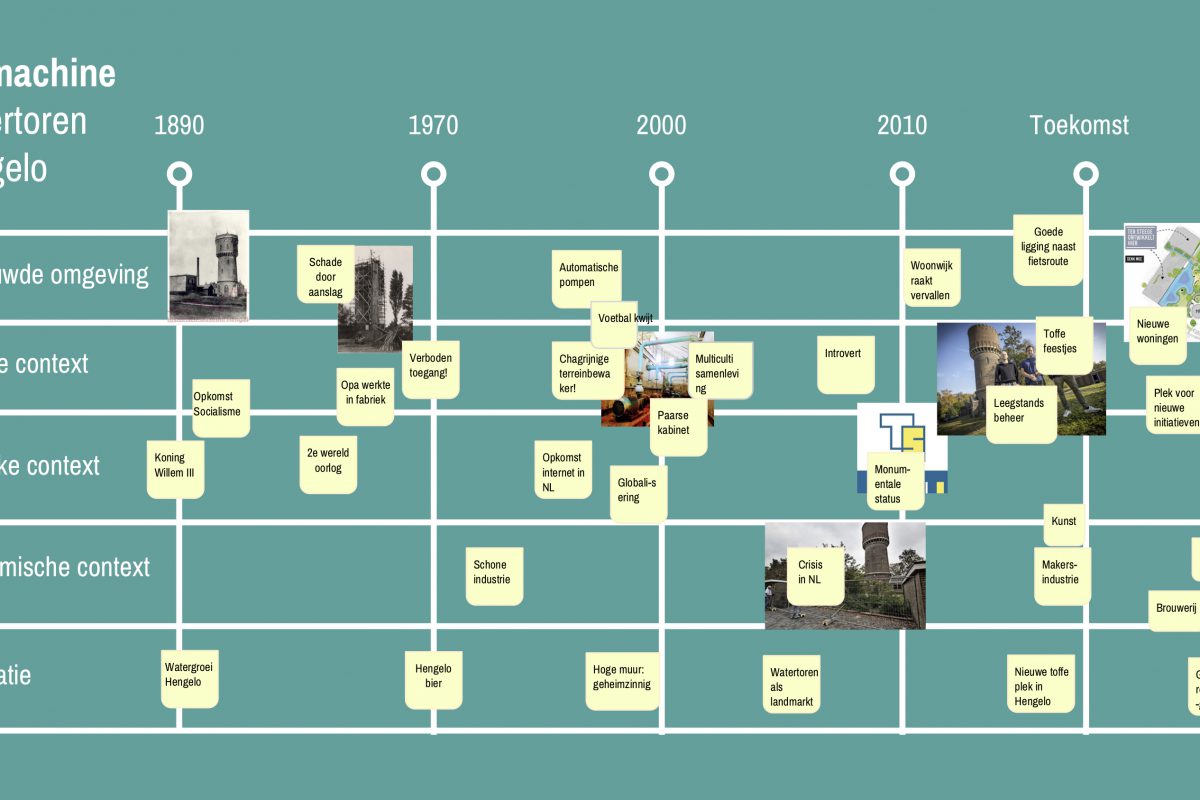

The Time Machine is a tool to discuss and connect past, present and future from a specific place together with stakeholders in one visual timeline. It’s important to let a broad scale of stakeholders participate from the very beginning, so that diversity and different personal perspectives are taken in account. In a journey through time, the stakeholders explore what the different characteristics of a place and its environment were. Inspired by the timeline of Failed Architecture, we research the following categories: built environment, social context, political context, economic context and reputation. Different studies point out that these categories influence the relationship people have with a place.5, 6 By doing that in different time periods, the timeline will form itself and show transformations and links of the place through time. The group collectively looks which elements from the past they want to bring with them to the present and the future of a place. It results in collective values and ambitions, brought together in a ‘value passport’: a document that provides access to and inspiration for developing a place in a sustainable and an inclusive way, provided by and for its users.

Mapping and involving stakeholders is only one step in the process. The most important element is to actually let them take ownership over the case. By creating the timeline, filled with their own memories, imagery, stories, emotions or even myths, but also by researching the facts of the place that influenced these memories and stories.

One of the lessons we’ve learned from our testround, is to avoid filtering content before and during the workshop on what we, as experts, think is of value for an area. The aim of the Time Machine is to get insights into the values and ambitions of the stakeholders, based on their memories, emotions and stories. A place doesn’t only have a meaning for its residents, they also want to have say over the future of the environment they live and work in. Only by giving them this opportunity, a recognizable and correct meaning can be added to the existing context of a place.

A place is never a clean slate, even if it’s a meadow or a vacant piece of land. Instead, we have come at a time where we work on a ‘tabula scripta’, a described slate: working with and from the existing, where it’s not only about the physical transformations, but also about social cohesion.7 The method of the Time Machine aims to add a meaningful layer to the existing and make the different stakeholders aware to take an active and involved role in this process of developing a building, street, area or city. The ‘value passport’ (the outcome of the workshop) could be used by anyone who wants to develop a place: from municipalities to housing associations or developers. For example, to create an area vision, zoning plan, to involve new users, entrepreneurs, residents in an active way or to program a site for a better connection with the neighbourhood. It results in a sustainable development to boost an area, which in turn can lead to an appreciation of value, not only real estate value, but more importantly the emotional value of people in a city. The Time Machine has thereby the possibility to develop places that can operate as a ‘lieux de memoire’ – an anchor by which society can strengthen its own history and identity.8

*The end result of the Time Machine has been made possible by Siënna Veelders, interns Lotte Hopstaken and Ilya Lindhout from STIPO, with lots of help and knowledge from Nancy van Asseldonk, Hester Dibbits, Riemer Knoop and students from the Reinwardt Academy, Lex de Jong (UrbanBoost), Anna Stolyarova (SAMA), Daniëlle Kuijten (ImagineIC), Martijn de Waal (Knowledge Mile), Sjoerd Feenstra (Urhahn) and Michiel van Iersel (Failed Architecture).

1. J.C.A. Kolen, “De biografie van het landschap. Naar een nieuwe benadering van het erfgoed van stad en land.”, Vakblad Vitruvius 1 (2007), 16-18.

2. C. van Boxtel en M. Grever, Verlangen naar tastbaar verleden. Erfgoed, onderwijs en historisch besef. (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2014), 43.

3. Grever, M., Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Erfgoed en Multiperspectiviteit. Expertmeeting Erfgoedonderwijs 16 juni 2016. (Rotterdam, 2016), 1-5. https://vakdidactiekgw.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Maria-Grever-Presentatie-Expertmeeting-Erfgoedonderwijs-16-06-2016.pdf.

4. J. Rana, “Moved by the tears of others: emotion networking in the heritage sphere” (23 June 2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1362581.

5. N. van Asseldonk, ed., Er is geen toen zonder nu. (Amsterdam: Reinwardt Academie, Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten, 2018), 6.

6. Verheul, W.J., Plaatsgebonden identiteit: Het anker voor stedelijke ontwikkeling. (Delft, 2015), 42. https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid:ead0c475-d764-4491-9f58-256fef1211b4/datastream/OBJ/download.

7. N. van Asseldonk, ed., Er is geen toen zonder nu. (Amsterdam: Reinwardt Academie, Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten, 2018), 6.

5. H. Dibbits, S. Elpers, P. J. Margry, A. van der Zeijden, Immaterieel erfgoed en volkscultuur. Almanak bij een actueel debat. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011), 25.