Keep up with our latest news and projects!

If you were to define your region, how would it look like on a map? If you had six snaps to show what makes worth living here and what you think should change, what would you photograph? These are a few of the questions I have been asking young people (16-24 years old) living in South East Wales. The research I am currently undertaking starts with a focus on their lived experiences and builds up to capture the youth’s different visions and aspirations for developing the area. I will analyse this information and point out the similarities and the differences with the official city-regional strategy for development.

The questions mentioned above are closely related to ‘The Wellbeing of Future Generations Act’, a piece of legislation that earned Wales its reputation for being a forward-thinking nation. The law, passed in 2015, requires public bodies to think in the long term and consider the impact their activities will have in the future, along the lines of sustainable development. Yet, the act is as much about the ‘what’ as it is about the ‘how’. Besides listing seven well-being goals that should be achieved, the Act includes five ways of working that public bodies must adopt: long-term-ness, prevention, integration, collaboration and involvement.

Close to my moral compass, it made me wonder what would happen if ‘the future generations’, instead of being a passive receiver of today’s decisions, would be involved and allowed to contribute to the vision of developing the South East Wales region, called Cardiff Capital Region.

Cardiff Capital Region is one of the many city-regional collaborations established in the UK through which different local authorities design joint projects, mostly focusing on economic development.

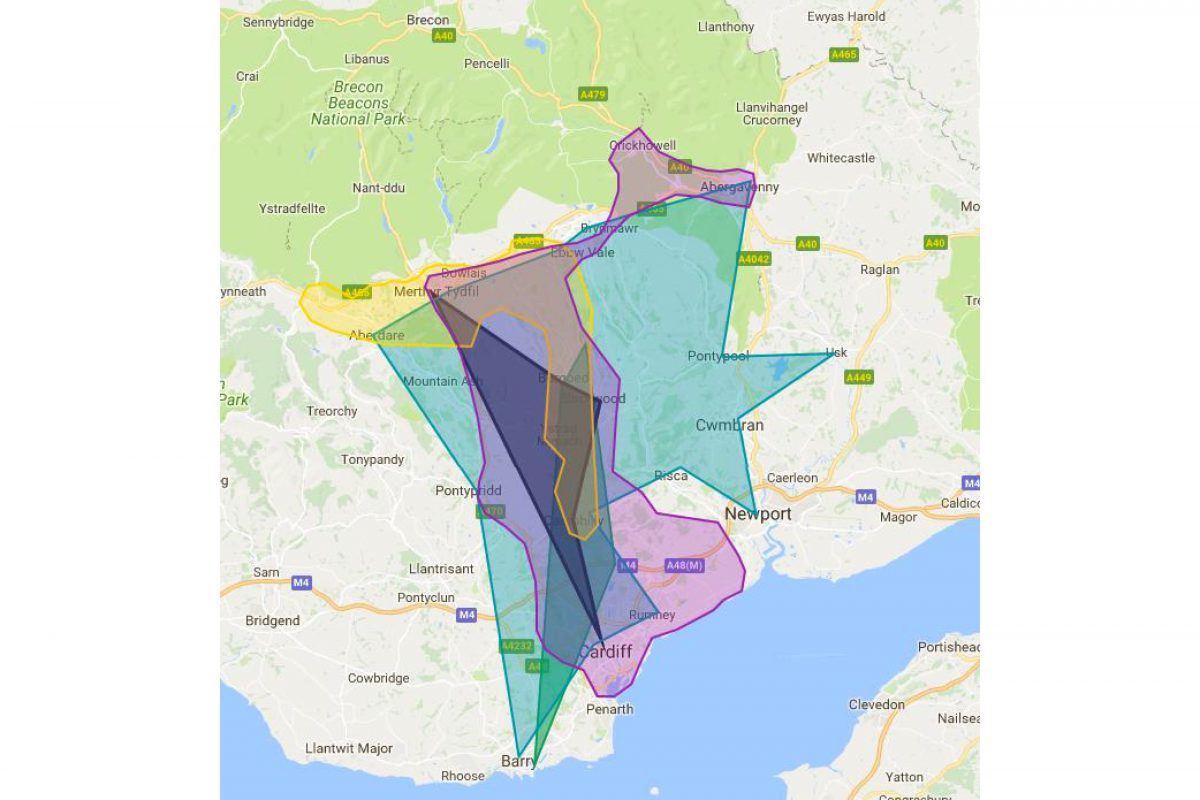

Curious about how young people (16-24) living in the city-region relate to this artificially created level, I look at individual ‘senses of region’. In small workshops, participants receive a definition and map their personal city-region, marking the coverage and sites which they consider remarkable.

Building on this geographic expression, the second research workshop uses the Photovoice method and asks young people to take photos of aspects they appreciate in their communities and features they would like to see changing. The session is structured in three parts: first, the participants present their own photos; then, all photos/subjects are discussed by the group; in the end, the most prevalent topics are chosen and the young people try to brainstorm on possible solutions or ways to bring about change.

Some of the most common topics are:

Five personal representations of the city-region, web-mapping workshop

Five personal representations of the city-region, web-mapping workshop

Litter, which is a hazard for the different ecosystems and also an eyesore, is often one of the most debated subjects in our workshops. The photos are often impressive in themselves, yet the group sessions lead to even more insightful discussions. Young people find various explanations for public space littering: from insufficient bins around towns, to deficient education, as well as lack of care for places. The latter, they say, has to do with many communities having lost their pride and hope for a better future. This narrative, common especially for the former industrial towns, is often reinforced by continuous negative media coverage. The stories we hear and tell ourselves define who we become. As such, people lose awareness and gratitude for aspects such as their rich Welsh culture and identity, impressive natural assets and tightly knit communities. This perception is furthermore strengthened by the lack of investment in public spaces and street fronts from the local authorities’ side.

‘There isn’t much outdoor seating by the college. This bench – I don’t think anyone’s ever sat on it.’ (Bridgend, BTEC Level 1 learners)

‘There isn’t much outdoor seating by the college. This bench – I don’t think anyone’s ever sat on it.’ (Bridgend, BTEC Level 1 learners)

‘It’s ridiculous that there’s so much rubbish right next to the bin. I wonder if people just look at the bin and think: “neaaah!’

(Bridgend, BTEC Level 1 learners)

‘It’s ridiculous that there’s so much rubbish right next to the bin. I wonder if people just look at the bin and think: “neaaah!’

(Bridgend, BTEC Level 1 learners)

‘This is a bungalow near my house, which has loads of random junk outside. This shows some people’s disregard for appearance and pride in their area.’

(Matthew Diggle, Pontlottyn, 18)

‘This is a bungalow near my house, which has loads of random junk outside. This shows some people’s disregard for appearance and pride in their area.’

(Matthew Diggle, Pontlottyn, 18)

'Streets in this area of Newport tend to be littered, there is always rubbish left. I feel that if the council and the local residents would work together, they could improve the environment and the area’s reputation.’

(Bethan Hill-Howells, Newport, 21)

'Streets in this area of Newport tend to be littered, there is always rubbish left. I feel that if the council and the local residents would work together, they could improve the environment and the area’s reputation.’

(Bethan Hill-Howells, Newport, 21)

After having identified an issue and the possible reasons behind it, the workshop ends with brainstorming on possible solutions. In the case of littered streets, we agreed there is a need for a jointed, comprehensive approach to break what has become a negative cycle.

The young participants believe it is important to start with the basics: education and information campaigns. Children, young people and most adults as well, need to understand where materials come from, what happens with the waste when disposed, the issues of not separating rubbish properly, the effect litter has on the environment, the time it takes for materials to decompose, etc. This can be easily done by schools as well as by local organisations.

A second step could be to raise people’s awareness and inspire them to take action. Instead of waiting for the local authorities to clean public spaces, citizen initiatives can be a more cost-efficient solution which allows people to understand the gravity of the problem, act to solve it and quite possibly form stronger communities based on a common goal: cleaning the places they love.

Finally, local governments should be actively trying to make waste disposal easy, encouraging correct recycling and composting. A step beyond would include strategies to curve consumption and waste altogether, through strategies such as public water fountains to reduce plastic bottle use, bottles and cans deposit return schemes or fees on single-use packaging.

Litter is only one of the few topics that stand out while talking to young people. Certainly, some of the issues discussed during workshops can be trivial and the solutions found far from revolutionary. However, interacting with young people is always refreshing and a constant reminder that they are experts of the places where they live. Ignoring their lived experiences bears the risk of misunderstanding and misrepresenting them, as citizens who do not only know the problems in their communities, but are often resourceful enough to help finding solutions as well.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover moreMy research is still ongoing but I have learned some important things:

For more information on the research, contact Lorena Axinte (find details on our authors page)