Keep up with our latest news and projects!

The Power of 10 is a simple idea. The foundation of the concept is that a good place has many activities and good reasons to be there, maybe 10 or more. Everybody sees a place in a different perspective, based on his or her own experiences, culture, and personality. The Power of 10 offers an easy, understandable framework that motivates residents and stakeholders to revitalise urban life. It shows that by starting efforts at a small scale, they can accomplish big things. The concept also provides people something tangible to strive for and helps them visualize what it takes to make their community great.

People and spaces come together to form the notion of place. Because people are at the heart of placemaking, creating a language for place is important. The average every day person, someone who lives in the area, should be able to easily understand these concepts. The Power of 10 provides this common language. People relate to this approach because it’s part of their life. It’s something they see as making sense; something they can fit in to. They are not handing over the process to someone else, another “expert”. They want to be involved and when they hear about the Power of 10 they get excited right away.

In order to continue building vibrant communities with prosperous streets, activities are the key. Going to town is a thing people enjoy doing. The activities will keep them coming for more. Unfortunately, in many communities, public gathering places like post-offices and libraries are moving outside of towns and off the main street in search of larger offices and more space. Keeping these public services—or what we call “community anchors”—in the city centre is key. The more functions that take place in town, the more lively and vibrant it will be.

In revitalisation projects, we assess how many and the type of activities available for people. There’s usually one nice thing to do. But then we ask: can we expand that into two, four, six other activities. How many quality places are located nearby, and how are they connected? Are there places that should be more meaningful but aren’t? Answering these questions will determine where residents and stakeholders should focus their energy.

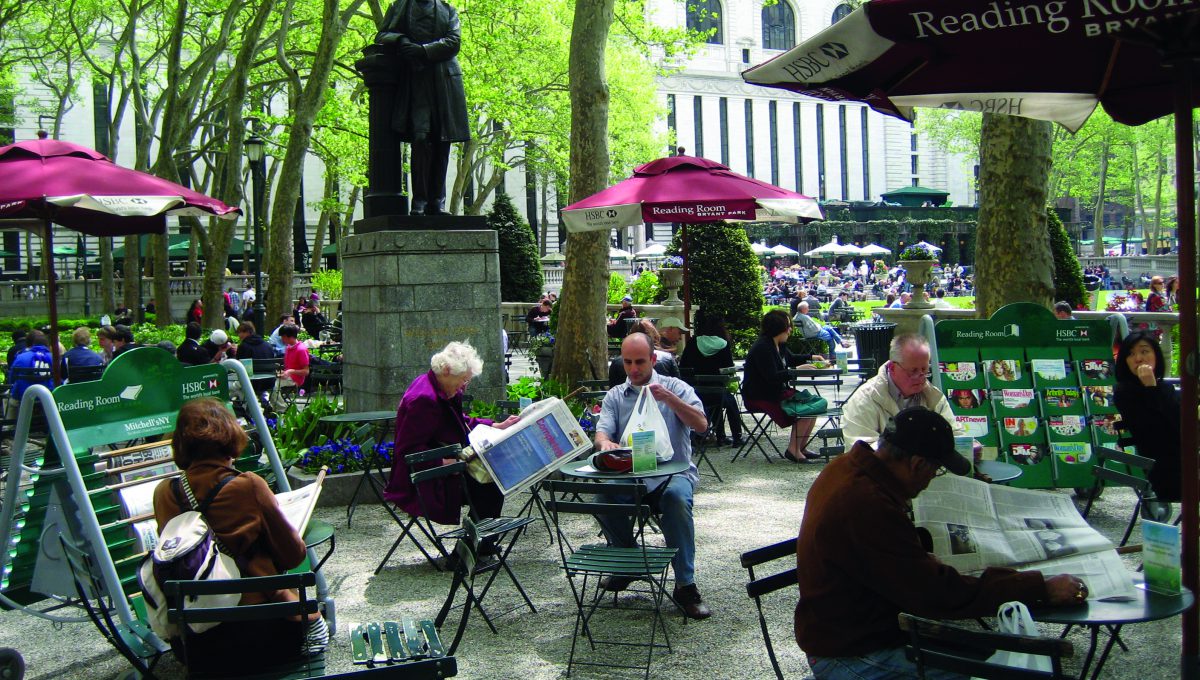

A huge success story is Bryant Park, in New York City. In the 1970s the park, at that time over-crowded with unkempt shrubbery and walled in with a high fence, was filled with squalor and drug dealers. The ordinary passer-by had no desire to enter the park. But by the 1990s, that had changed. The work of William “Holly” Whyte greatly contributed to the park’s turn-around. He encouraged the redesign of the entrances, the lowering of shrubs that blocked the view into the park, the placement of smallscale cafés and kiosks, and the establishment of a privately funded management entity for security and maintenance headed by one large business improvement district (BID), Bryant Park Corporation. It was also his idea to place about 2,500 moveable chairs on the park grounds. The effect: people came to sit, to watch, to enjoy others’ company.

The carousel in Bryant Park: a good example of the Power of Ten. It also serves as an excellent example to illustrate the principle of “Triangulation”. Notice that the Carousel has other activities attached to it, such as a playful and engaging ticket booth and a “reading room” in scale for children. Just beside it (out of the picture) is a “game area” for children and a special area for children’s parties.

The carousel in Bryant Park: a good example of the Power of Ten. It also serves as an excellent example to illustrate the principle of “Triangulation”. Notice that the Carousel has other activities attached to it, such as a playful and engaging ticket booth and a “reading room” in scale for children. Just beside it (out of the picture) is a “game area” for children and a special area for children’s parties.

The Power of 10 can be a base for starting any placemaking process. By definition, placemaking occurs on the ground floor, the city at eye level. The sidewalk is often a starting point. There’s something nice about the sidewalk. This is where the principle of “Triangulation” comes in, whereby additional elements are added to a particular activity, giving the activity more interest. What do we need on the sidewalk to keep people walking and to keep their interest? There must be something to look at or to engage with; the idea is to encourage the pedestrian throughout their walking experience.

In our work on main streets, that something is storefronts, and in this book they are called plinths. Creating continuity on the sidewalk and with storefronts is essential to the city at eye level. Storefronts must come up to property line—that is what encourages people to walk, to shop, to remain interested. Anything that takes attention away from the storefronts is problematic. For example, sudden set-backs in the property line, large-scaled columns or pillars, and “dead zones” all interrupt the walking route and vision line, creating difficulty for the shops to carry out their goal: inviting people in.

Vacant walls, which are ever-present in our cities today, are also dead zones. As soon as a pedestrian arrives in a dead zone, they become uninterested in walking or shopping or anything. The question then becomes: how can we fill up those dead zones with life and potential activity? Posters, displays, greenery, historic markers, anything can keep alive dead space. Dead zones are in fact a great opportunity for the community to get together and create something relevant and meaningful to the community. The goal is to provide interest in as much square-feet as possible.

In most cases, individual merchants can make small changes to their storefronts. Because the very nature of being a merchant is to think about the inside—the products they sell, the displays, store lay-out and flow, advertisements—it might be difficult for them to think about the outside of the building. Sometimes we take the merchant by the hand, walk outside, and show them their building. This is how they can become involved in triangulation. In most cases, small, inexpensive additions can be made that not only help the image of the business but also help engage the pedestrian, by providing more interest to the sidewalk. Such additions can include a new imaginative hanging sign, installing a colourful awning, providing creative window displays, adding a bench for sitting, or placing merchandise on the sidewalk.

Bryant Park, New York

Bryant Park, New York

The “Reading Room” in Bryant Park: one of the more successful activities in the park and a good example of the Power of Ten

The “Reading Room” in Bryant Park: one of the more successful activities in the park and a good example of the Power of Ten

To bring about change, implementation is where it starts. It’s one thing to look to the city or planning department for guidance and leadership. But the real and best test to any revitalisation project is community involvement. The merchants or the city do not own the downtown, the people own it. The case of Bryant Park illustrates how business districts and urban commercial neighbourhoods can revitalise by using small scale, innovative approaches that encourage the prosperity of local businesses. It can be as simple as putting out chairs, planting flowers, and quickly repairing anything broken. By involving the community, no project is ever ‘done’. It will continue to be modified, improved, and adjusted. This is a defining quality of a vibrant urban place. It’s not enough to have just one great place in a neighbourhood, or one great neighbourhood in a city. A collection of interesting communities is the ultimate goal.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover more