Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Historically, towns emerged as a result of the exchange between travellers on pathways and vendors selling their wares from booths. The booths later became buildings and the pathways became streets, but the exchange between those who came and went and those who stayed, continued to be the key element. Urban buildings were oriented towards urban spaces by necessity. Since then, many urban functions moved indoors, and shops, institutions and organisations have grown larger. In the process, urban buildings have become bigger and correspondingly introspective and self-sufficient.

However, pedestrians must be able to walk around cities, urban structures continue to form the walls of public space, and people continue to have close encounters with buildings. What we want from the ground floor of urban buildings is vastly different from what we want from the other storeys. The ground floor is where building and town meet, where we urbanites have our close encounters with buildings, where we can touch and be touched by them.

In this context, the ground floors of all buildings are important and serve many purposes, depending on the location of the building, its functions and the surrounding space. The front or entrance façade, particularly in buildings where the façade faces the street and sidewalk, is especially significant. Generally speaking, close encounters with buildings can be divided into a few main groups.

Walking alongside buildings. Movement can be parallel with buildings: people walk past or alongside. Movement can also be at right angles to the façade. People go to and from, approach, enter and leave.

Standing, sitting or engaged in activities next to buildings. Residents and users go outside or stand in the doorway for a break. Chairs and tables are placed along the façade where access is easy, sitters’ backs are protected and local climate is best. Ground-floor façades are also an attractive place for urban users who don’t live in the buildings. The edge effect refers to people’s preference for staying at the edges of space, where their presence is more discreet and they command a particularly good view of the space. Edges and transition zones between buildings and city spaces become the natural place for a wide variety of potential activities that link inside functions with outside street life.

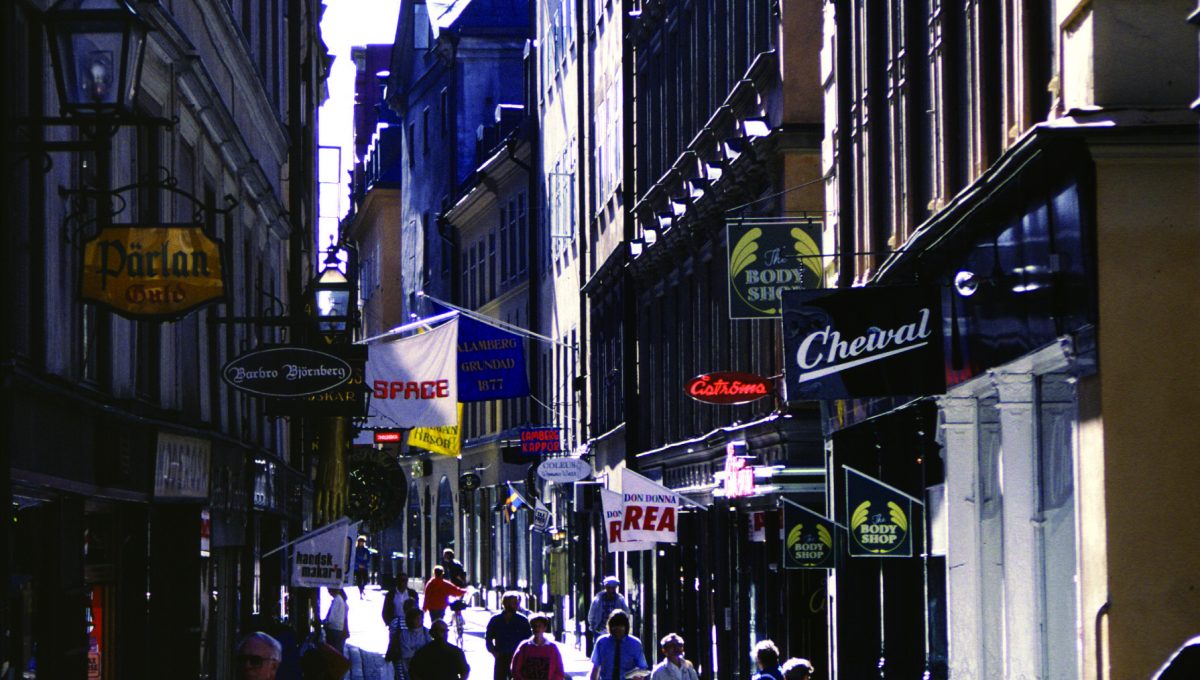

Seeing in and out of buildings visually connect activities. Visual contact is close up and personal for pedestrians on city sidewalks, thus the rhythm of the opportunities offered is crucial to the richness of the pedestrian experience. The number of doors, windows, niches, columns, shop windows, display details, signs and decorations is significant (Jacobs, 1995).

Exterior architecture is inextricably tied to the vantage points for viewing. With respect to building architecture, what we see depends on the angles at which we see it. As pedestrians, we have to stand quite far away to see a building in its entirety. When we come closer, we have to stretch our necks and lean our heads far back to take in the whole building. Few structures are designed for viewing from that angle. As we move closer the upper storeys gradually disappear from view, until we can only see the ground floor, or when we are really close, only a section, like the details on doors and façades.

Closer up, our other senses are activated. Here, at close range, we can see, hear, smell and feel all the details, not only of the ground floor, but often of the display window and shop interior as well. Our senses of smell, touch and taste are closely connected to our emotions. Ground-floor façades emotionally impact us more than the rest of the building or the street, which we sense from a much greater distance and with correspondingly lower intensity. Short distances provide intense and emotionally powerful experiences. We transfer the perceptions of intimacy, meaning and emotional impact from our meetings with people to our meetings with buildings.

While our perception of public space depends on viewpoint and distance, the speed at which we move is crucial. Our senses are designed to perceive and process sensory impressions while moving at about 5 km/h: walking pace. Architecture that embodies 5 km/h details combines the best of two worlds: a glimpse of the town hall tower or distant hills at the end of the street and the close-up contact of ground-floor façades.

Contrasting with ‘slow’ architecture is the 60 km/h architecture along roads dominated by vehicles, where large spaces and signs are necessary since drivers and passengers cannot perceive detail when moving at this speed. These two scales pose conflict in modern cities. Pedestrians are often forced to walk in 60 km/h urban landscapes, while new urban buildings are designed as boring and sterile 60 km/h buildings in traditional 5 km/h streets.

Scale & Rythm: 5 km/h architecture

Scale & Rythm: 5 km/h architecture

Street life: chatting by the door

Street life: chatting by the door

Closed façades with uniform functions: passive and boring

Closed façades with uniform functions: passive and boring

The closer we get to buildings, the more we perceive and remember the content of our field of vision. If the ground floors are interesting and varied, the urban environment is inviting and enriching. If the ground floors are closed or lack detail, the urban experience is correspondingly flat and impersonal.

Studies provide information about many different aspects of city streets. Ground-floor façades clearly impact public life. In front of active façades, pedestrians move slower, more people stop, and more activities take place on the friendlier, more populated street segments. When we add it all up, we see that the number of stops and other activities is seven times greater in front of active rather than passive façades.

One main conclusion, then, is that lifeless, closed façades pacify while open and interesting façades activate urban users. It is important to note that the activity level of a street is quantitative in principle—a measure of how many people and how much life and activity available. However, a higher activity level does not necessarily indicate a better urban quality. We cannot only focus on how many people walk, stop, sit and stand; it is also important to look at quality content, wealth of experiences, and yes, the simple delight in being in cities.

Knowledge about the factors that positively influence urban life is an important instrument for planning better cities. Included in this type of knowledge are the most compelling arguments for promoting well-conceived ground-floor and façade policies: the variety of experiences and the sheer pleasure of journeying through the city. What we need to do is encourage and insist on freedom of movement for pedestrians in their own city. And ground-floor architecture plays a key role in this context.

Transparency: open windows and façades

Transparency: open windows and façades

Appeal to senses, also at night

Appeal to senses, also at night

It can occasionally be refreshing when a building does not insist on a friendly conversation with the people entering and leaving or passing by. However, it can also be a problem when a lack of dialogue becomes ordinary practice in designing new buildings. When new buildings are planted in places people frequently use, the buildings must learn to make meaningful conversation with city spaces and the people in them. Buildings and city spaces must be seen and treated as a unified being that breathes as one. And ground floors, in keeping with tradition and good sensory arguments, must have a uniquely detailed and welcoming design.

Good close encounter architecture is vital for good cities.

Gehl Architects (1998), Byrum and Byliv – Aker Brygge [Public Space and Public Life in Aker Brygge, in Danish], Oslo.

Gehl Architects (2000), Transparens – Kontakt mellem ude og inde, Aker Brygge [Transparency – contact between inside and outside in Aker Brygge, in Danish]

A.B. Jacobs (1995), Great Streets, MIT Press, Cambridge

MA

This article first has been published in URBAN DESIGN International (2006) 11, 29–47, and was summarized with permission of Jan Gehl.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover moreIt is important to analyse functions in new urban areas and establish where close encounter architecture can play a role. Where are the most important pedestrian routes? Which façades are the most important? Where will people in the new urban area come in close contact with buildings? Where and how can the design of new buildings contribute to life and vitality in new urban areas? The question is not what the new urban context can do for your building, but what your new building can do for the context.

The overriding planning principle has to be: first life, then space, then buildings. Thus the first step of a design plan must be to establish the location and quality criteria for the city’s most prominent public spaces, based on specific preferences about the character and extent of public life in the new part of town. Urban design guidelines can then be drawn up for new buildings (Gehl Architects 1998 & 2000). Sample guidelines that can be used for project development: