Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Parks and playground are often planned and designed with a specific demographic in mind; for example, facilities for small children are never co-located with the ones for young adults. Further, the latter are often designed for structured activities such as for sports or learning, with limited considerations about how unstructured playful activities might be encouraged for and enjoyed by older children and others (Rawlinson & Guaralda, 2012). At a social level, children are not only segregated in specific facilities where they can be protected from potential dangers of the broader society but as users of “youth-friendly spaces”, they are also divided according to age groups, gender and vocation.

In Australia, there is a strong risk-averse culture, in part due to the widely acknowledged conservatism of the population (Nilan, Julian, & Germov, 2007). Different levels of governments implement top-down regulations so to sanitise specific aspects of everyday lives, in order to minimise chances of conflicts or accidents. Fencing, barriers and warning signage are a common feature of Australian public spaces; as such, many Australian urban environments are highly regulated, zoned, and controlled (Shearer & Walters, 2015).

This chapter reports on four years of public consultation processes undertaken at a different level of government and in different contexts within South-East Queensland, one of the fastest-growing regions in Australia. Our findings suggest that the ‘playground’ is seen as the realm of the children, who are then perceived as less entitled to comment on the broader urban fabric because their experience is limited to dedicated “child-friendly” spaces that are not necessarily integrated with other urban uses. The chapter reflects on how South-East Queensland cities are designed in a regimented and perhaps fragmented way which tends to exclude or underrepresented certain categories of residents, especially children.

Community consultations run from 2013 to 2018 in several locations within South-East Queensland to investigate different aspects of placemaking, place identity, safety and people’s perception of their city. Locations included Brisbane city centre, Kelvin Grove Urban Village, peri-urban sites in Logan City Council, the regional centres of Pomona and Nambour on the Sunshine Coast. All citizens were able to freely share their stories and express their thoughts. Participants contributed in different ways; some attended workshops, others responded to surveys; some contributed drawings to illustrate their vision or wrote a letter to their own suburb. In some cases, participants generated maps pinning their preferred places or posting notes to highlights different urban conditions. Participants were left free to interpret the different questions asked as they preferred. Data collection was not influenced by any previous briefing to potential participants, who were simply asked to share what was important to them in their community. During this process, children were not specifically targeted, but several young people, some as young as 5, participated.

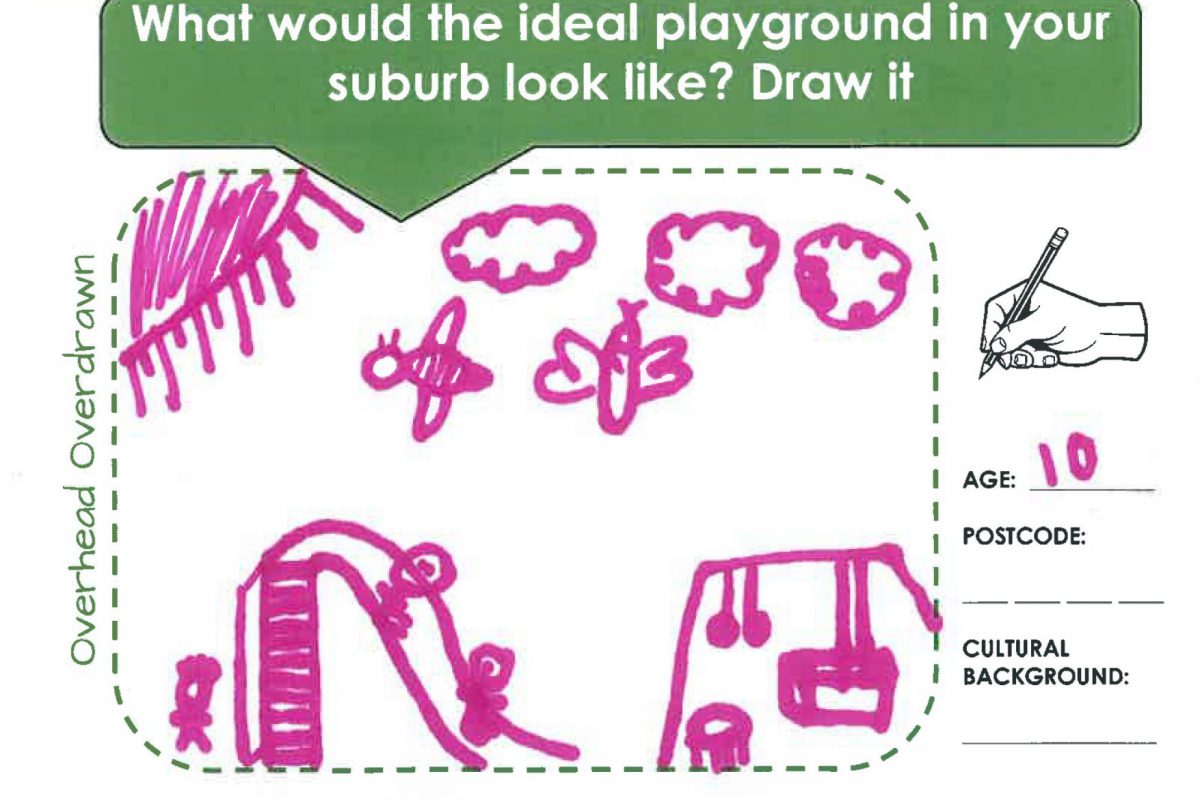

Data gathered demonstrated how children living in different urban conditions share a similar view in terms of their built environment and their perceived role within it. When prompted to comment on their suburb, the majority of children focused on spaces traditionally designed for youth, nominally parks and playgrounds. When specifically asked to draft an ideal playground, the majority of the children provided images of quite ordinary spaces, with slides and swings. Few participants suggested more unusual equipment, for example flying foxes or water slides, but the overall concept of the playground was the one of a delimited space with just one function to engage a specific demographic. Interestingly, adults addressing the same questions have provided images of fenced playgrounds, pointing at safety as their main concern.

When the meaning of the actual experience of living in the suburb was investigated, it became evident that children were stressing the importance of social relationships. A place was meaningful to them because a friend or a relative lived there; because they could meet with people to play and socialise. Even when children were stating a sense of attachment to their suburb, this was limited to their experience of green areas and playgrounds.

Our findings show that children in South-East Queensland have a limited experience of urban environments and especially how they can live in it. Suburban areas are mainly structured around parks, streets and private commercial malls; city centres follow the British pattern based on street grids, malls and parks, with the limited number of other public spaces, such as squares. Children in other countries have more sophisticated experience in urban environments. They experience daily engagement with a number of different public spaces, which display more mixed uses and integrated activities than in their Australian counterparts. Youngsters in South-East Queensland do not display a deep sense of urbanity and they passively conform to patterns imposed by Euclidean planning and the notion of separate land uses. The attitude towards cities developed as youngsters, shaped by segregation and compartmentation, they may lead to the development of behavioural patterns that influence how Australian adults use and perceive urban environments – for example, teenagers and young adults aged 16-25 have often provided individualistic feedback of what means to them being an urban dweller. Some respondents have pointed with annoyance to the perceived control society has on them, or to the interferences their local community has on their lifestyle.

Considering how in many countries spaces for children and youth are integrated into the urban fabric, Australia has a comparatively segmented approach to the design of cities and public spaces overall, thereby limiting possibilities for intergenerational exchange. A strong agenda to promote inclusive, intergenerational and collaboratively designed public spaces in Australian cities is necessary to face a rapid urban growth, which is mostly still in line with obsolete design paradigms that may result in an even more fragmented social structure.

This article belongs to a series of stories about the city at eye level for kids! You can access the full book online in PDF or pre-order your hardcopy to be delivered to your home.

Get your book here– Nilan, P. M., Julian, R., & Germov, J. (2007). Australian youth: social and cultural issues. Frenchs Forest, N.S.W: Pearson Education Australia.

– Rawlinson, C., & Guaralda, M. (2012). Chaos and creativity of play: designing emotional engagement in public spaces. Paper presented at Out of control: Proceedings of 8th International Design and Emotion Conference: Out of Control, London, United Kingdom.

– Shearer, S., & Walters, P. (2015). Young people’s lived experience of the ‘street’ in North Lakes master-planned estate. Children’s Geographies, 13(5), 604- 617. DOI: 10.1080/14733285.2014.939835