Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Can we use market developments to create a more inclusive society? Bend-the-flow as opposed to go-with-the-flow, in a direction where social and communal gains play a part in determining the result of area development. Examining a number of good examples in relation to each other reveals that there is also room for gentrification with a soft edge.

People migrating to cities, a growing economy, and higher land and property prices – that’s good news for a lot of people, because it means more houses are being built, and it’s giving people without jobs a chance to find work and increase their income. The economy is running full steam ahead. Higher property prices can create opportunities for redevelopment in inner city areas, and given the demand for housing in cities, this means less attractive districts stand to be upgraded as well. An economy that’s doing its job in a conservative-liberal market also means exclusion through disimprovement. Disimprovement as a result of the cappuccinofication of streets, which are livened up by new businesses, but at the expense of familiar local enterprises that vanish without fanfare. The universally recognisable couleur locale is thus under threat, even though it’s precisely the movement of value during economic growth that can make good things happen. So, is the process of gentrification in itself not exactly an opportunity for the city?

Ultimately – in a completely free market – gentrification is more likely to promote exclusiveness than inclusiveness. Inclusiveness gives everyone a chance to succeed by providing them with opportunities, and it’s based on equality: everyone participates and shares. In this article we define inclusiveness as a situation in which everyone has a place to reside and to live in, and in which people have room to come into their own. The inclusive city, then, is a place where everyone can reside, live and come into their own. That puts tremendous pressure on the city. It requires districts or neighbourhoods with sufficient economic activity and facilities where there is also space to live and where residents can interact. It also requires authorities to have the ability to allow everyone to participate (www.vernieuwdestad.nl, 2018).

What would it be like if, during a time of growth, adjustments were introduced or prices curbed so that stores and workshops (work/business spaces) remained affordable for, say, first and second-generation businesses and residents? Or that they too evolved and eventually moved, but that there were still opportunities for others to start up somewhere or to carry out activities that don’t necessarily yield immediate financial gain but are nonetheless of added value to the district or neighbourhood as a whole?

Developing policy without trying to understand the market often misfires. In the US, the rent ceiling did not cause the market to level off but instead minimised costs for property owners, who stopped investing in maintenance. These kinds of policies push market developments in the wrong direction. In the Netherlands, many households don’t have suitable housing, based on their incomes, and the social housing sector is in a gridlock because there’s no flexibility. For decades, the housing policy has been trying to find the right types of affordable housing that won’t continuously create a housing imbalance. Indeed, the question is whether a type of housing can be found in the context of market developments that can reallocate value creation differently or hold on to it. Holding on to it could contribute to a different form of allocation, so that residential and work spaces, for example, remain accessible in the long term for a large diversity of target groups and the residents of the city.

In this essay we would like to address a number of examples that promote inclusiveness and essentially approach market forces from a different vantage point, attempting to diminish, eliminate or make adjustments to them at the policy level. It is not an overall analysis or a plea to build an inclusive society based on these types of projects or policies; rather, it’s about increasing our knowledge on how to use positive market forces for other purposes than merely financial value creation.

It is vital that we invest in land and real estate: not only more from a spatial consideration but also in order to make the right adjustments that correspond to our changing living and working requirements. This has to be an efficient process, and it (often) requires professionals to make it run smoothly. We strongly believe that making optimal and diverse use of our cities and space generates value creation on many fronts: social, communal, cultural and ultimately often financial as well, in terms of land and property value.

The hard facts of the real estate market: trust is the foundation of value creation.

The crisis in the land and property market has taught us important lessons. The devaluation of land and property value was the consequence of a system in deadlock, but also of a loss of trust. That created widespread vacancy, falling returns, a deteriorating image of the areas, which set a downward spiral into motion. The striking thing about this development is that it can be turned into a positive. Giving meaning to areas increases trust among residents, businesses and investors, which galvanises a process of increased investment, less vacancy and an improved image. This is also reflected by the fact that these areas increase their output. More than anything else, this increased output is creating added value for the areas’ economy, society and local financial sector.

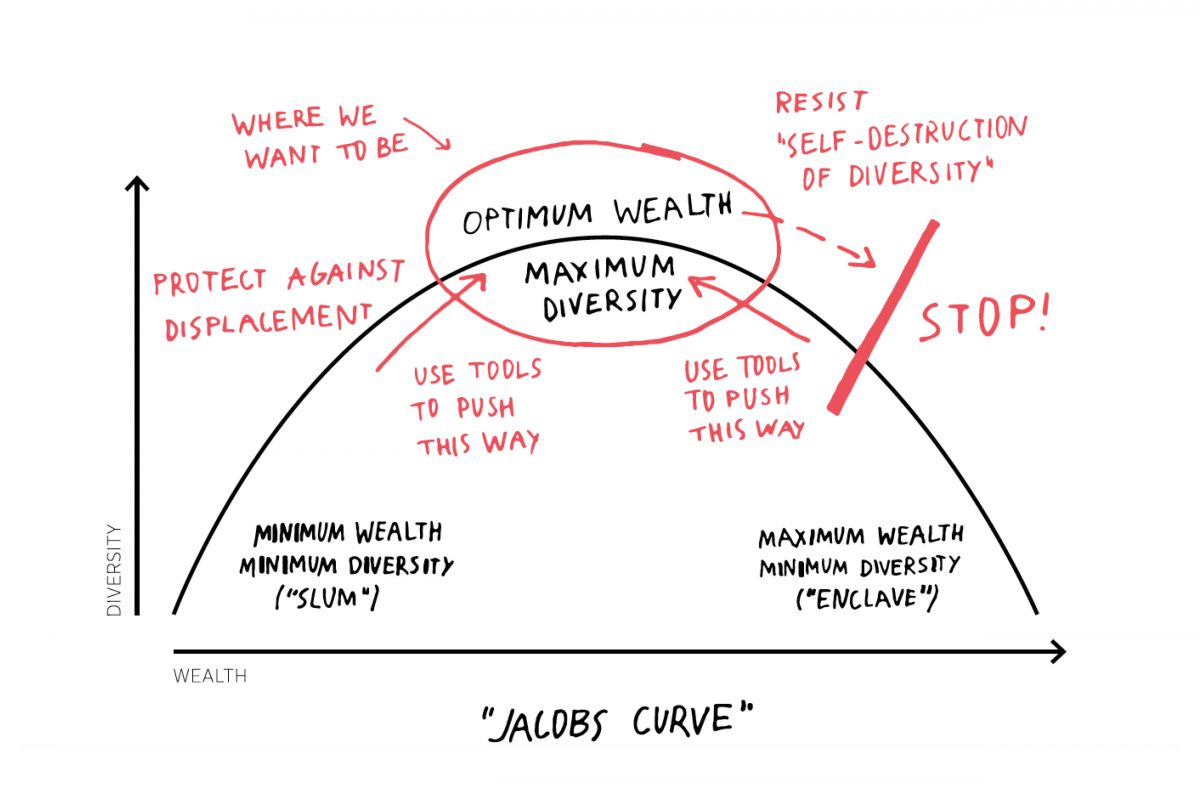

In his article in this book, Michael Mehaffy describes (as he did at the Cities for All conference in Stockholm in April 2018) how Jane Jacobs analysed gentrification as an upward and downward movement. Viewed from a market and financial management perspective there are a number of interesting developments taking place that provide opportunities for where we want to be.

New development strategies through placemaking

City makers and placemakers have proven themselves adept at driving value creation. Now that the economic situation has improved and is enhancing growth and redevelopment, the question is whether they can become a permanent fixture in area development. There is a great opportunity for new area developers and the more traditional parties (who focus on construction) to forge partnerships. The question isn’t whether we should opt for old or new area development, it’s about which combination we decide to go for. In that sense, every task will be specifically defined and require a tailored approach. The programming needs both placemaking, and social and communal value creation, as well as a healthy business case for area transformation. The absence of this combination of types of area development with placemakers and city makers often leads to the disappearance of new interesting activities in the area.

It’s therefore of crucial importance that we develop a business case for placemaking. Not only does it have to include financial and economic aspects, but also the added value for society and the community. That will make the concept of ‘value creation’ real. And consequently the added value of placemaking will become visible so that it can be adequately acknowledged. The inclusiveness will become visible and space will have been created for anyone who wants to join in.

Good residential-work areas require adequate area management: The Plinth Ltd

Increasingly we’re trying to develop urban areas that have a good mix of residential and work space. Many areas have set aside a role for new economic activities, either aimed at manufacturing in the city or on innovation.

In the Netherlands, creating sufficient housing in the coming years is viewed as our main challenge (at the moment). The Dutch government’s aim is to accomplish this in a healthy sustainable environment. Perhaps the biggest challenge in this is to find sufficient (physical) space for new workplaces. That means being extremely aware of the role that work is going to take on in new transformation areas.

Once that’s clear, the activities in the initial phase of the transformation can be launched. The business case for placemaking could then be tailored to coincide with the area’s future function in the overall context of the city. Placemaking is transient by nature. Placemaking doesn’t focus on transience, but transience can be used to reinforce a more balanced process aimed at the growth of certain types of activity in an area. To achieve that, you need room to experiment, especially during the initial phase. But a balanced supply of business space is also needed in the long term. That requires coordinated programming and area management.

An example is a conceptual experiment called The Plinth Ltd. People working in area development are increasingly turning to this concept. The Plinth Ltd is about connecting activities in a street or district. It could involve coordinated branding and shared rentals or sales, as well as the long-term programming, managing and operating of spaces in an area. In addition to the programming, it evolves into a form of financial organisation that manages the share of affordable workplaces in such a way that there’s place for innovation, starters and more social and cultural activities. And it provides space (literally) for residents in the neighbourhood to reach their full potential.

Working together to make and keep workplaces affordable

Working together to make and keep workplaces affordable is possible by evenly distributing the immediate revenue from real estate (rentals) with the aim of creating a more liveable and manageable area. Another aim is to retain the couleur locale, which often increases an area’s output. The government can assist as well. It has yet to be seen, however, whether a targeted government policy aimed at a certain percentage of (financially) affordable workplaces is the ideal response. In the Netherlands, this corresponds to a segmentation, for example, that amounts to 30% social housing.

But it’s precisely when an area defines the preconditions itself (rental restrictions, duration of contracts, target groups) that this appears to be most effective. Especially when the parties that benefit first, perhaps end up paying a little more later. Evenly sharing revenue is therefore a management tool in a broader context: the development of the economy in an area, for example. Senior businesses help junior businesses because once upon a time they were also given an affordable workplace when they were getting started.

Other forms of organisation in the public domain

How can we secure pre-financing? Pre-financing gives an idea of the chances of succeeding and is thus essential for many forms of value creation. District management and the management of (private) public space is especially popular in Anglo-Saxon countries, often with successful and positive results. The United States uses a Business Improvement District (BID) structure for that purpose. In a BID structure, all owners contribute a little extra, which is ‘collected’ by the municipality in the form of a premium on real estate tax. This is used to fund the maintenance and programming of an area. The investments are used to make areas more attractive, but also to hold programming/events, for example. In inner city areas, the programming acts as a ‘catalyst’ for new business models. At a later stage, the contribution from property owners in the area can be adjusted.

The Netherlands has the Business Investment Zone (BIZ), which is only valid and deployed in industrial estates. If we were to link this model to the transformation of urban areas, then that would generate a financial organisational model that is better suited to our transformation task and which could simultaneously provide placemaking with the necessary pre-investment. This BIZ would have to be extended to transformation areas, however. It would then offer a new financial organisational structure.

Private financing aimed at high social returns

The need to also highlight communal and social value in value creation is an incentive for private financing that focuses more on achieving social than financial returns. This is already the case with monumental real estate or the financing of real estate concerned with art and culture, which is popular with private investors. This is not happening to the same extent in area development, though there are excellent examples in Germany and Switzerland. In Berlin the Tris Foundation and the Edith Marion Foundation, among others, are financing the redevelopment of Holzmarkt and the ExRotaPrintFactory. The financing is meant for long-term involvement by funding land or property with private money combined with funds from banks (socials banks). The portfolio management focuses on safeguarding and monitoring the social and communal contribution these projects make in addition to the question of whether the interest and debt payments will be paid back. The impact of these funds on the surrounding area is usually what’s most visible. That’s why it makes sense to approach investors situated ‘around the corner’ when raising funds. Couleur locale, but then of a different variety.

In the Netherlands, there are an increasing number of initiatives using social impact funds for financing. These projects (e.g. De Wasserij in Rotterdam) have agreed to permanently rent out half of the work studios at low rent, while another portion is rented at market value. The Stadmakersfonds (City Makers Fund) was founded in March 2019 in Utrecht based on German and Swiss examples.

Using own funds makes it possible to finance projects that otherwise wouldn’t see the light of day. Making long-term ‘financial agreements’ situate the projects, so to speak, in a different market segment.

Collective building and living

New forms of collaboration in area and property development can help to create new structures that mitigate market forces or channel value creation in another way.

But there’s more going on. The trend in society is to do more collectively. Expressions of this include: the sharing economy (cars and bicycles), more communal living (cooperatives) and communal building (collectives). Collective building means working together on a design, but also doing part of the project development yourself, including contracting a construction company. The real collective private commissioning (Collectief Particulier Opdrachtgeverschap – CPO) as we know it in the Netherlands in its purest form is most commonly used for projects with single-family homes or unoccupied plots.

Increasingly, groups or collectives are building apartment complexes in inner city areas. It often concerns co-commissioning, in which future residents form a collective and contribute to the draft, make decisions together about the architecture and completely design the dwelling (type, plan, etc.) themselves. Professional parties (advisors, builders or developers) take the construction part off their hands and thus also eliminate a number of key risks. As a result, the financial management varies in each project. Often a cooperative is established in which future owners unite, thus defining the commissioning group. The cooperative also provides an adequate organisation for the operation and management of a building. This collective way of developing provides (more) control over the product, and for owner-occupied houses there’s essentially collective financing as well. All future buyers contribute part of the money needed to finance the land, construction etc. through their mortgages.

When collective building turns into collective living, it creates the opportunity to manage property in a different way. Of course, freehold tenure of a unit can be acquired in an owned building that can be freely sold on the market. With rental cooperatives there’s the option of limiting rent through mutual agreement, as the group determines the collective’s financial policy. There are many Miethaussyndicaten (rented property syndicates) in Germany and Switzerland, which buy land to build social housing and housing for the mid-priced rental segment. The collective finances part of it with its own money and part of it through banks. In time, the loan is paid back and value is created through the property. The Miethaussyndicaten use these assets to set up new collectives and to build their own capital. There are even rental cooperatives that pay a small premium on the rent (‘solidarity interest’), which are used to save up for other (new) cooperatives.

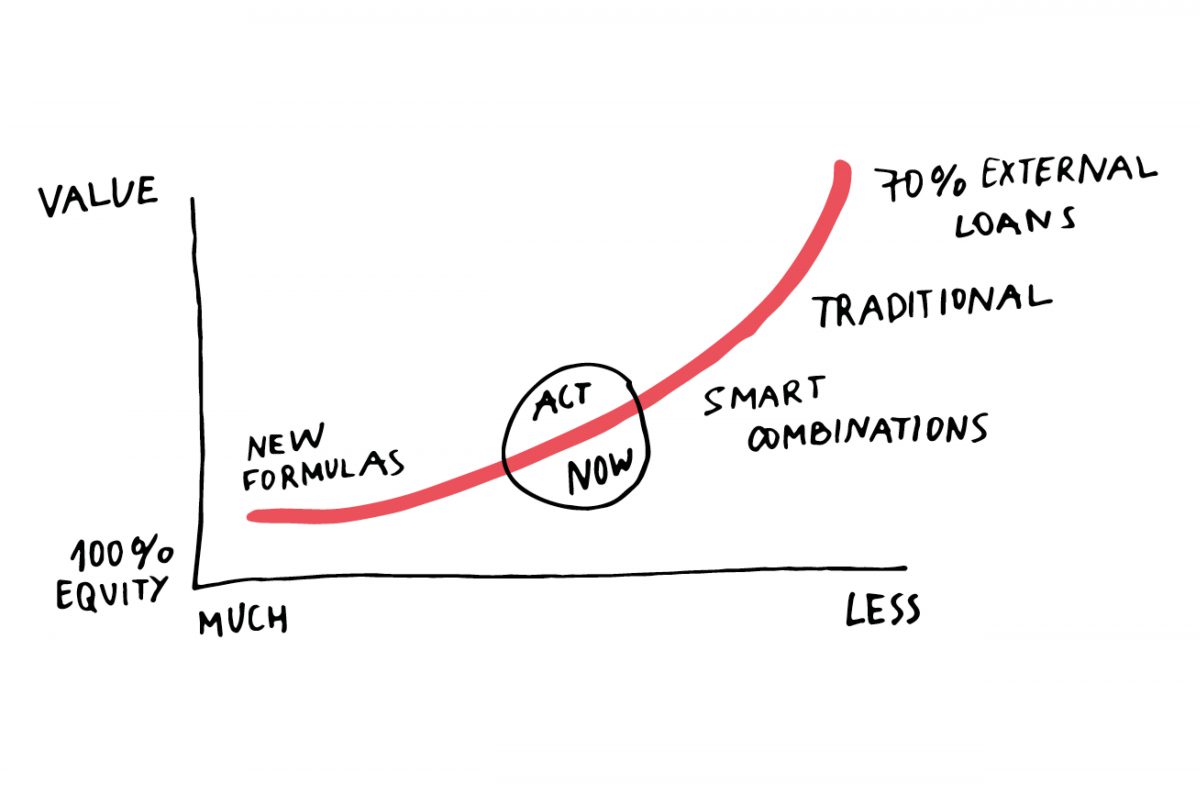

What makes this construction so special? First of all, these buildings are simply developed in a commercial land and property market where land is bought to build these rented properties. Once completed, part of the value creation is used for rental policy, which allows the rent to be adjusted and the cooperative to prevent exorbitant rent increases by implementing its own policy. And the rental cooperatives can use their own money to guarantee part of the financing, as a result of which the rental cooperatives are also able to secure good financial conditions from banks for loan capital. In the Netherlands, this kind of collective living is viewed as an interesting option in which residents have more control over their property, even when it concerns rental properties. Lack of own capital (banks often require an input of at least 30%) is the bottleneck for initiatives in the feasibility phase.

Collective building makes collective living possible. This creates opportunities for collective management and developing your own rent policy, which can limit the degree to which you rely on the commercial market. With control comes risk: in that sense, the German and Swiss examples point to potential ways of mitigating this risk, namely scale up, work together and develop policy for value creation.

The six developments discussed here and their accompanying examples all have a number of aspects in common.

First of all, there’s the assumption that choices can be made within the workings of the market forces and the land and property markets regarding the organisation of process, management, use and ownership. In addition, it’s also a question of working in phases or looking at finances from a broader perspective: for example, limiting the immediate gains in order to achieve higher indirect returns. Tools aimed at collectivity, such as the BID, help in that respect. So do private funds, however, which pursue other objectives than merely achieving returns. Indeed, it’s also about how you define return and your ability to view it as an amalgamation of financial, social and communal gains.

But it starts with area development that focuses on creating a balance which leads to inclusiveness. The scale (building, district, area) and the context in which space is provided for growth and development are important for the ultimate shape that alternative funding, financing and organisation subsequently will take.

Many of these matters are relatively new, so it will take a while before they will manage to become a permanent fixture in area development. It comes down to a different way of focusing on returns: Gentlyfication makes more possible.

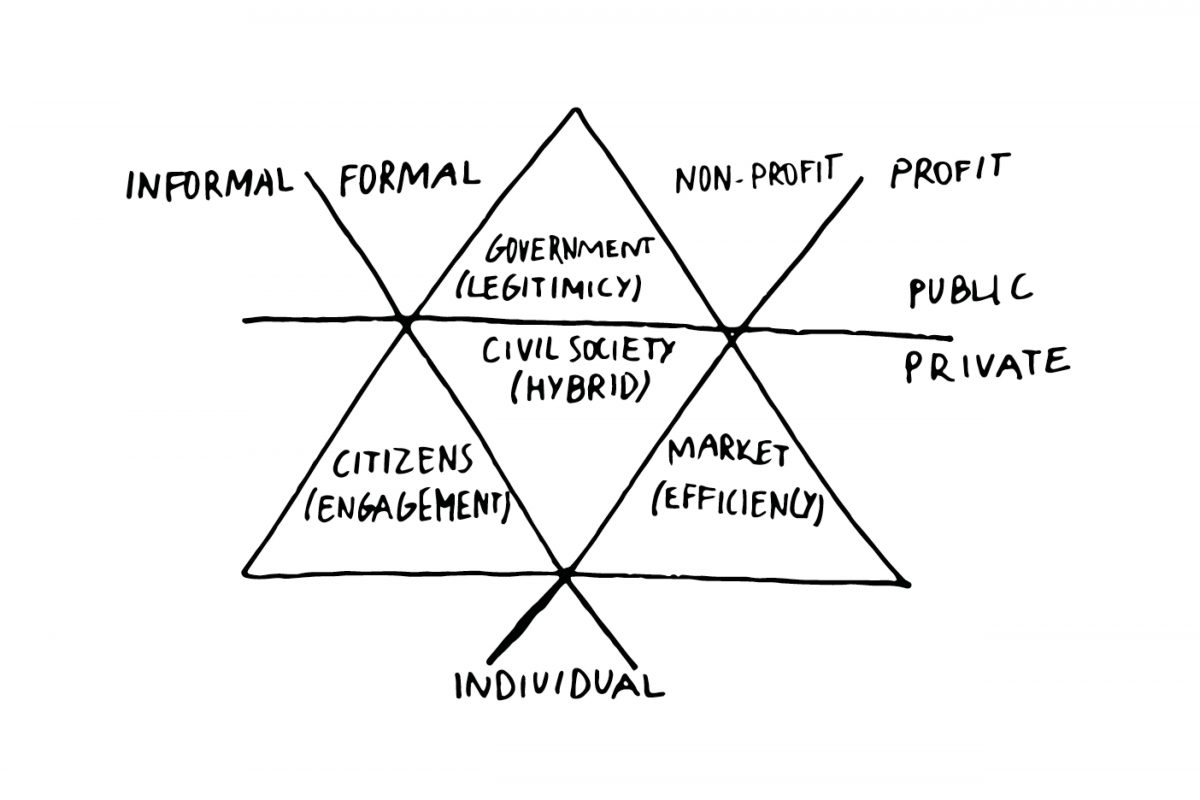

Bottom-up initiatives give area development strength and identity. Top-down is needed for continuity and direction. Collaboration begins somewhere in between. It’s important to connect the public, the private and citizenry. The triangle in the middle of Pestoff’s pyramid would seem a good position from which to work: there is room here for co-production, co-creation but also co-buying, co-financing, and so on. There is the risk, however, that ownership falls by the wayside, as a result of which this triangle turns into a Bermuda triangle (W.J. Verheul 2019). So, as discussed, for a solid foundation we need new forms of organisation (impact financing), tools (BIDs) and partnerships (area cooperatives). And ownership: not only of land or property, but rather of the task and the ambition.

By prioritising the task and ambition, and taking into account new forms of collaboration and organisation, the ‘way to go’ should be an easy path to traverse. Gentlyfication instead of gentrification then leads to inclusiveness.