Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Cities are hubs for the exchange of goods, culture, knowledge and ideas. The city street is the stage where this exchange takes place: it is the access to the home and the company, and the passage to other places within and outside of the city. For centuries city streets had a natural vibrancy and dynamic, where various functions came together. Until mid 20th century the street was an integrated system of movement and social and economic life. This changed in the 1960s and 1970s when large-scale interventions in the urban fabric emphasized traffic, and put the importance for exchange in second place.

Precisely at that time of traffic breakthroughs, people like Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch and Gordon Cullen pointed out the importance of the human-scale of the street. They indicated that the city has to be considered from how people experience the city: at eye level. Their publications now seem more relevant than ever. Since the early 1980s we see a growing awareness that the viability of the city can be improved by linking the different scales of the city. The location of a street or square in the city as a whole, the connection with the various networks, and their social and economic characteristics, are crucial. And so is the plinth where the interaction between the street and the building takes place.

Every city street endures a process of rise and fall, and time leaves its traces on the city and the plinths. Technical innovations, traffic concepts, the economy, and public opinions change over time and influence the urban form and the public space. This article gives a general overview for each period of city transition from three perspectives: the city form, the street, and the plinth.

Paris, a strong connection between buildings, plinth and street creates an attractive city

Paris, a strong connection between buildings, plinth and street creates an attractive city

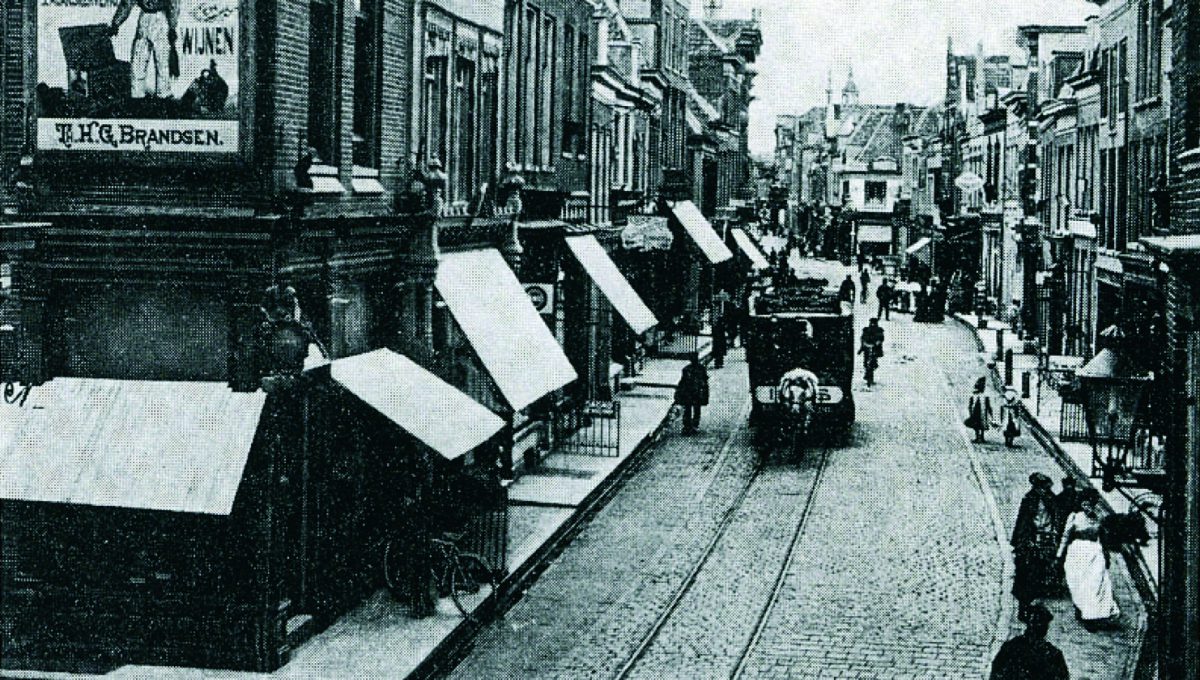

Langestraat Amersfoort, streets used to have a dynamic of living, working and transport

Langestraat Amersfoort, streets used to have a dynamic of living, working and transport

Many cities were founded at intersections of roads or waterways, for example Berlin, Hamburg, Valencia, Seville, New York, London or Amsterdam. At these crossroads exchange of goods and ideas took place and an urban core was established with main urban functions as a harbour, market, bourse, weigh house, church, and town hall – often with a central square. Fortifications formed a delineation from the countryside. Due to growth of trade, also crafts and population increased. Initially this led to growth within the city, but soon the urban area expanded around the main roads to the city. With these expansions, fortifications also shifted.

The main streets coincided with natural roads and waterways and were the connections to the hinterland. Social and economic life took place on the squares, streets, quays and bridges, where the markets were held. In the 16th century the markets specialized in different types such as fish and fruit

markets. Street names still remind us of the goods that were once traded, e.g. Butterbridge, Haymarket, etc. Until the 19th century, the majority of freight transport took place on the water. With the flourishing of the cities and increase of traffic and activity, the number of streets and bridges grew and the busiest streets and squares were paved with cobblestones. Regulations for buildings increased: rules for façade alignment, bay windows and stalls allowed passage of traffic. Building height was also limited so sunlight can fall into the street.

Specialized shopping streets as we know them now didn’t exist in the cities before the 19th century. Living, working and trading took place in the same building and street, where craftsmen displayed merchandise in front of their homes. There was no clear separation between private and public, and merchandise was exposed on the street. Later these stalls became permanent and were incorporated in the façades. From the late Middle Ages the passage zone between the street and the home was marked by a stoop or porch. The stoop (a raised plate) ensured that carts did not come too close to the house and displayed goods. A street consisted of series of individual stoops and landings, divided by benches and fences. In northern Italian cities like Bologna, arcades formed this passage between the house and the street and provided shadow. The doors were open all day in the 15th and 16th century – anyone could look and walk inside. In the next centuries, the streetscape of façades, plinths and public space was more united.

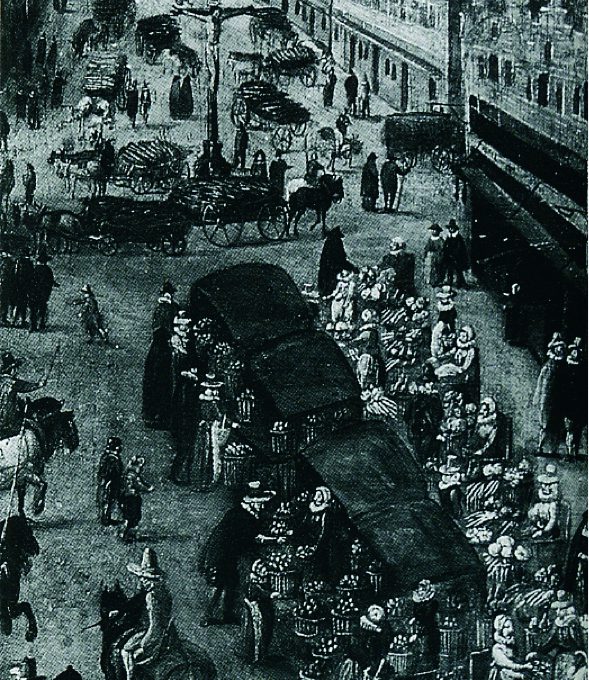

Antwerp Market, around 1600

Antwerp Market, around 1600

Fabric Market in Bologna, 1411

Fabric Market in Bologna, 1411

The Jansstraat in Haarlem, painted by Gerrit Berckheyde in 1680, shows the alignment of the façades

The Jansstraat in Haarlem, painted by Gerrit Berckheyde in 1680, shows the alignment of the façades

Medieval streetscape: public space as an extension of the house

Medieval streetscape: public space as an extension of the house

Street in London, 18th century: the houses follow a continuous line, the shop signs are back, and bollards separating the road from the sidewalks

Street in London, 18th century: the houses follow a continuous line, the shop signs are back, and bollards separating the road from the sidewalks

In the 19th century, new transportation modes arose. Railways became important next to waterways for the increasing transport of people and goods. Ports, industrial and residential areas were built outside the city or at the former fortifications. Also the new stations lay on the city boundary and became new core areas with a concentration of infrastructure, housing, industry and public space. More and more people moved out of the old inner city to this new areas and neighbouring municipalities, easily accessible by train or tram.

Characteristic of the city plans in this period were the monumental axes with a separation between the busy main streets with shops and businesses, and the more quiet residential streets behind. In residential areas shops only occurred on street corners, while in the inner-city a separation of functions

took place: housing was less important and the number of (department) stores and offices increased, leading to a scaling in the block. Due to industrial production and stock storage, the first stores appeared in the 19th century, soon followed by department stores and grand bazaars. Skyscrapers were only constructed in US cities in this period, and in order to avoid dark streets New York adopted a zoning law for the height and the width of towers in 1916.

The separation of functions and new city areas and neighbourhoods led to increased traffic. In the city, circulation improved due to breakthroughs and new bridges. In Paris (under direction of Baron Haussmann) and in London (e.g. the construction of Regent Street) the modernization of the city is accompanied by new and wide boulevards through the historic city centre. From the 19th century onwards traffic flows are separated; since 1861 sidewalk were created important to give pedestrian

their own place in the crowded streets. Also separate tramways and loading streets were installed, and trees were planted to provide a division. In Vienna the new tramlines on the former fortifications formed the Vienna Ring, connecting the main buildings of the city (town hall, parliament, royal palaces

and theatres) to each other in a grandiose design.

Paris and New York were the prominent cities in the 19th and early 20th century. Department stores and shops were developed along the major routes and squares, around the stations, and on streets with trams running through. The Paris ‘grands magasins’ such as Le Bon Marché and Printemps, and New York office buildings were soon copied by other cities, creating new boulevards with shopping and office buildings.

The emergence of shops and offices led to an entirely different street. The façades were transformed into attractive storefronts to display the goods, with a purpose to entice the passerby. It was common to have the windows as full as possible. The carefully designed store fronts were constructed of a closed and decorated base with a large glass front. The entrance was set back, creating a small alcove. The street plinth thus existed as a series of different windows in shape, height, width and decorations. The shopping streets and façades were followed by a new phenomenon, first introduced in Paris, Brussels and Milan: the shopping galleria or passage, arcades with luxury shops, not only to shop but also to stroll.

Budapest East Station and Square, 1912

Budapest East Station and Square, 1912

Chicago street view, 1920s

Chicago street view, 1920s

Boulevard des Champs Elysées in Paris, around 1880

Boulevard des Champs Elysées in Paris, around 1880

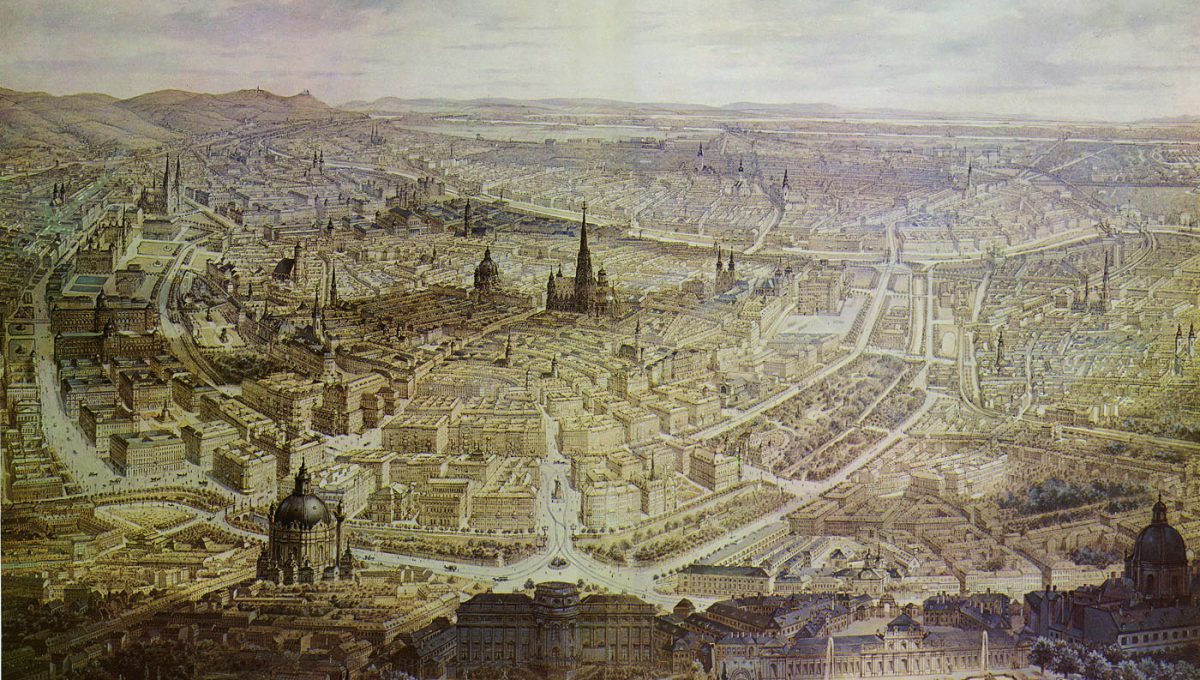

Vienna Ringstrasse, developed in the second half of the 19th century

Vienna Ringstrasse, developed in the second half of the 19th century

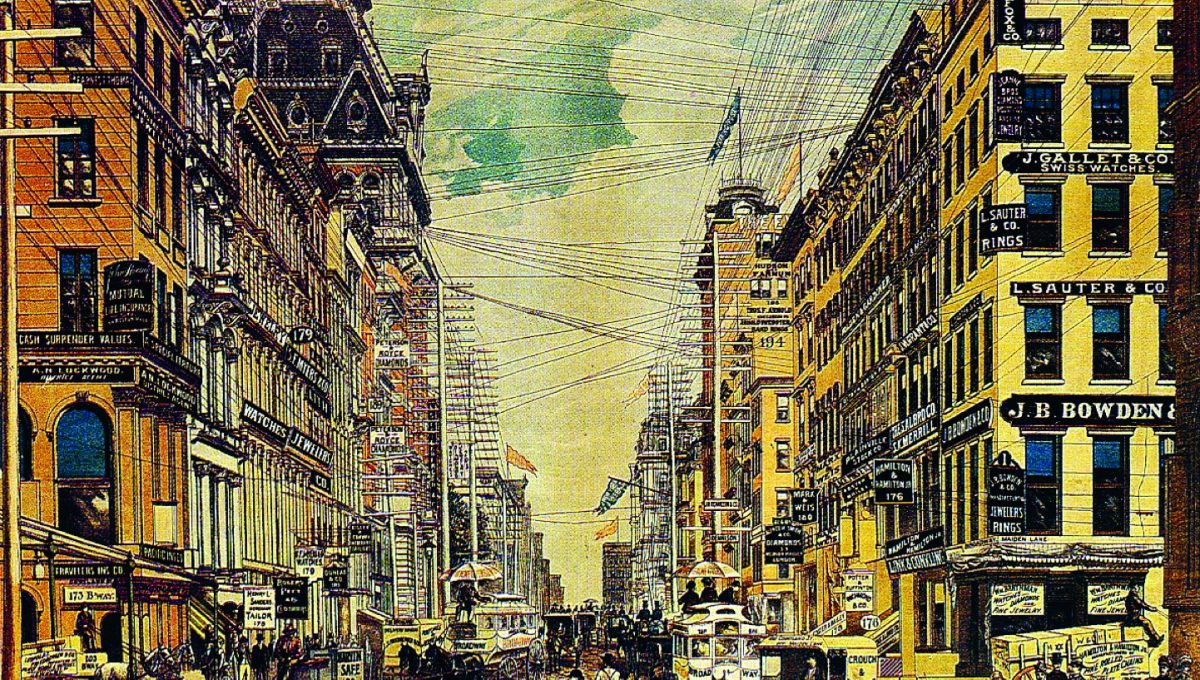

New York, around 1900

New York, around 1900

Shop façades from ca. 1900 in The Hague

Shop façades from ca. 1900 in The Hague

The first shopping mall in America: Cleveland, 1890

The first shopping mall in America: Cleveland, 1890

After World War II, the accessibility of the city centre for cars and the new urban expansions had a priority. The growth of car use in this period was enormous: the number of cars in the Netherlands for instance increased from 30,000 in 1945 to 4,000,000 in 1980. The main planning concept was a separation between living, working, amenities and traffic. The town centres developed into central locations for offices and amenities. The vacant areas in the during the war severely damaged cities, were now used to accommodate increased traffic. Other cities focused on traffic engineering to connect the inner-city with new ring roads, for example in Utrecht, the Netherlands. This development of breakthroughs for car traffic and large-scale urban renewal was also criticised, among others by Jane

Jacobs with her plea for mixed-use human-scale neighbourhood streets.

New neighbourhoods for living were developed outside the existing city in New Towns and Garden Cities, with in-between highways and railroad as major barriers. These plans were derived from the ideas of CIAM, such as the plan for the Ville Radieuse of Le Corbusier who had a great aversion to the ‘rue corridor’, the enclosed street. His ideas were implemented in many residential projects in Europe with elevated streets and high-rise buildings. Instead of closed urban blocks, the urban fabric consisted of an open allotment with a mix of low, medium and high-rise buildings in a green setting. In accordance with the prevailing planning concept in Europe, districts were divided into small neighbourhoods with small shopping areas and a central shopping centre in the district. In the 1960s and 1970s a deterioration of city centres occurred due to the move of residents to the suburbs, especially in the US where new shopping centres with large parking lots became the standard for the shopping.

To improve traffic safety new means were invented for the separation of traffic flows and control: zebra crossings, traffic lights, traffic hills, and roundabouts. The streets were further divided and the cohesive space disappears. In the suburbs appeared a strong hierarchy between main access roads, neighbourhood roads, and residential streets, often with an independent network of footpaths and cycle paths on a different level. The separation between traffic road and shopping street was complete when

all functions were incorporated into a superstructure or, as in Minneapolis, when the pedestrian was led from one inner world to the other via ‘skyways’.

The new urban concept of open building allotments allowed a new design for stores with windows in the front, supply and storage via back streets, and separated entrances for the dwellings above. This

allowed continuous shopping façades along the street, as can be seen on the Lijnbaan in Rotterdam, the first pedestrian shopping street in Europe. The transparent storefronts with lots of glass and showcases, and the glass kiosks give a strong interaction between interior and public space. Also historic city streets were modernized with display cases and new store fronts. The plinths had an open

design to entice passersby to step inside whether in newly structured or in historic inner cities. In contrast, suburbia plinths were closed off and most shopping centres turned their back to the surroundings.

The Bijlmer-district Amsterdam, as originally intended with internal pedestrian streets and green living

The Bijlmer-district Amsterdam, as originally intended with internal pedestrian streets and green living

Lijnbaan Rotterdam, 1954: new pedestrian shopping street for renewal of the bombed city centre - © Stadsontwikkeling Rotterdam

Lijnbaan Rotterdam, 1954: new pedestrian shopping street for renewal of the bombed city centre - © Stadsontwikkeling Rotterdam

The muted Catharijnesingel-canal in Utrecht, built in the sixties

The muted Catharijnesingel-canal in Utrecht, built in the sixties

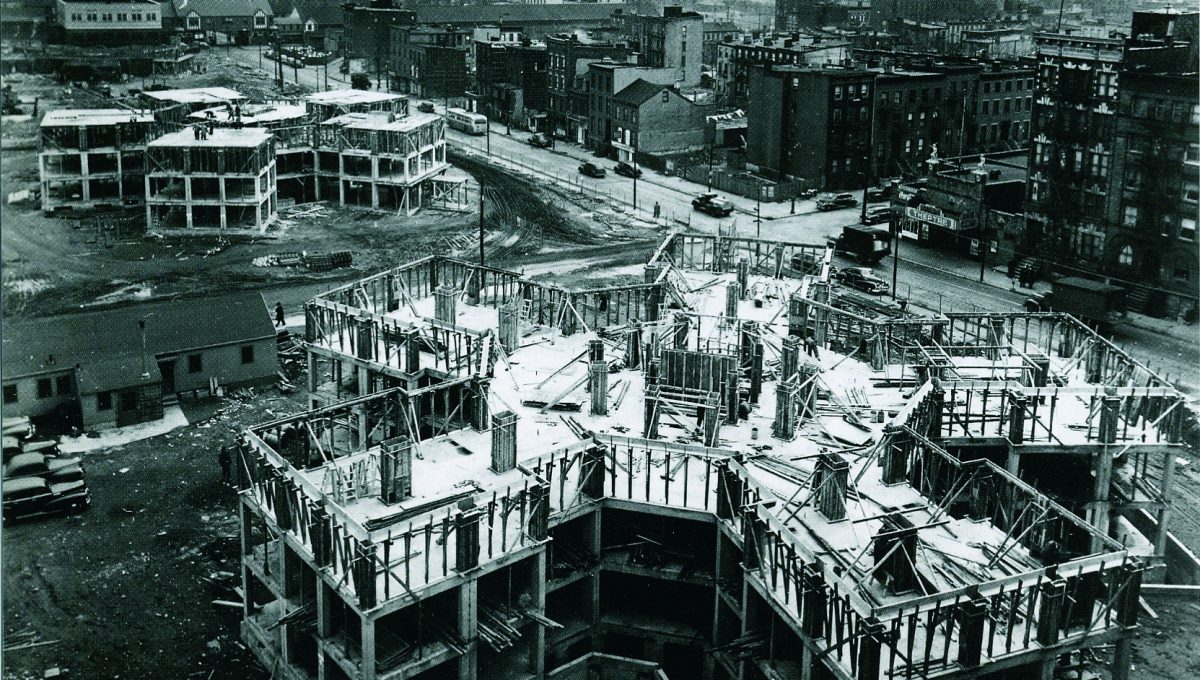

Large-scale new developments in New York

Large-scale new developments in New York

La Ville Radieuse: Le Corbusier’s portrayal of his ideal for free-standing housing in green spaces

La Ville Radieuse: Le Corbusier’s portrayal of his ideal for free-standing housing in green spaces

Skyways in Minneapolis dating from the 1960s and 1970s provide pedestrian connections between buildings - © Streetview Google Maps

Skyways in Minneapolis dating from the 1960s and 1970s provide pedestrian connections between buildings - © Streetview Google Maps

After the decades of modernism, we see a departure from the separation of functions, especially in traffic. The Buchanan Report ‘Traffic in Towns’ in 1963 and the 1973 oil crisis questioned the dominance of car traffic. Cities started to ward off cars and improved the ‘hospitality’ of the city: instead of traffic breakthroughs, the historic urban fabric is used for urban renewal. Architects from the international Team X (among others Aldo van Eyck, Alison and Peter Smithson) emphasized human-scale buildings and streets, and a transition (or hybird) zone between private and public spaces. Terms like ‘hospitality’ were used within the architectural debate. In many inner cities old structures from the 19th century were demolished and replaced by new buildings characterised by human-scale architecture. Even the larger projects were small-scale oriented such as the Forum Les Halles in Paris, a new shopping centre that replaced the historic marketplace of Les Halles. Most new shops and supermarkets were developed in centrally located shopping malls close to the new residential

areas, as already had been done in the US in the previous decade.

With a new focus on human-scale cities, public space was rediscovered as an area to walk, meet and gather. People again visited the inner-city to stroll, go to the theatre and meet each other. An important milestone was the closure of shopping streets for car access, becoming pedestrian zones: in 1966 Germany had 63 pedestrian streets and in 1977 up to 370. In the inner-city of Utrecht a pedestrian area was developed and the wharves along the canals opened for cafés in the 1970s. The design of new residential streets was also influenced by the ‘hospitality’ concept, where pedestrians are favoured. This concept started as ‘Woonerf’ (home zone street) in the Netherlands, where the car is a guest and pedestrians are favoured. This idea was followed in other countries such as the ‘Wohnstrasse’ in Austria.

Although the re-evaluation of the historical city halted large scale demolishing of old buildings and city fabric, inner city areas still were replaced with new but small-scale housing developments. Most new buildings were internal-oriented and the relationship between house and public space was part of the architectural form. The plinths however are mostly focused on housing and living and not on shops, services and restaurants – only few streets were designated as new shopping streets. In many urban renewal areas, the plinths were not designed with shops or public functions but instead with closed façades.

Small scale urban renewal in Zwolle (architects Aldo van Eyck and Theo Bosch)

Small scale urban renewal in Zwolle (architects Aldo van Eyck and Theo Bosch)

Forum Les Halles, Paris: constructed in 1977, demolished in 2010 and to be replaced by a new Forum

Forum Les Halles, Paris: constructed in 1977, demolished in 2010 and to be replaced by a new Forum

Stroget in Copenhagen was already partly closed for cars in 1962, at present being the longest pedestrian shopping street in Europe

Stroget in Copenhagen was already partly closed for cars in 1962, at present being the longest pedestrian shopping street in Europe

Wohnstrasse in Austria: residential areas in the city

Wohnstrasse in Austria: residential areas in the city

Urban renewal street: plinths lack public functions

Urban renewal street: plinths lack public functions

Renewed interest in inner cities in the 1980s carried on in the 1990s and the beginning of the 21st century with a focus on public space. The rise of sidewalk bars and cafés and specialized retail signified the rediscovery of the centre as a place for meeting, amusement, and shopping as leisure activity. Barcelona was the first city stimulating the renewal of the cityscape by the redevelopment of public space in relation to the Olympic Games of 1992. Public realm was regarded as an important

outdoor space for citizens, such as green parks and squares. The revitalisation of the existing inner-city acquires lots of attention. Also in other cities beautification started with the improvement of the quality and coherence of the public space. An important motivation to city leaders for the renewal of the public space was the city’s economy. The city was rigged to attract people with festivals and events in this postmodern age: a visit turned into an experience for which the city is the decor, sometimes focused

on a historical period. Also new cities try to adapt the look and feel of historical towns, with small shops and individual façades.

Besides the public realm, many new projects were developed in and around European city centres. Important key projects were the station areas as entrances to the city, due to a new High Speed Rail network in Europe. New stations and hubs were developed, and gave an economic boost to the city centres such as Euralille. Abandoned harbours and old industrial areas, close to the inner-cities, were redeveloped for housing, offices, leisure and places of culture. Large area developments included property, new infrastructure, public space and new landmarks. Well-known examples are Hafencity in Hamburg, the Eastern Docklands in Amsterdam, the Kop van Zuid with the Erasmus-bridge in Rotterdam, the renewal of Bilbao and the new Guggenheim, and in London the banks of the Thames around the Tate Modern, housed in an old power station.

The reconquest of public space created more space for pedestrians and reduces the car in the city centre. In Lyon new underground parking spaces were built for a total of 12 000 cars. Paris redesigned

the Boulevard des Champs Elysées without parking strips and widened the sidewalks so people can once again stroll along the shops and restaurants. As an alternative for separating traffic, the “Shared Space” approach creates a common street for everyone without separation between car, bicycle and

pedestrian. Exhibition Road in London has been redeveloped according to this concept, giving it a more people-oriented look and feel.

The interaction between the street and the adjacent houses, shops and restaurants became stronger. Plinth and public space were designed as related and coherent spaces within the city shopping experience. New coffee bars and cafes scattered throughout the city centre and the 19th-century neighbourhoods where creative professionals can work and do business. Internet and social media increased the need of physical places where you can meet.

Today there’s still a need to connect buildings to the street with a vibrant façade and plinth. This not only applies to new buildings and their ground floors, but also to the redevelopment of existing buildings and infrastructure. The transformation of many historic structures shows that the city always

changes. In this the need to adapt and design good and attractive plinths is necessary for the city dweller and the city at eye level.

In Barcelona the revitalisation of the city is boosted by

the investments in public space

In Barcelona the revitalisation of the city is boosted by

the investments in public space

Amsterdam Eastern Docklands, old harbours transformed in a new urban area

Amsterdam Eastern Docklands, old harbours transformed in a new urban area

Shared space Exhibition Road, London

Shared space Exhibition Road, London

Shopping centre Beurstraverse in Rotterdam - © Stadsontwikkeling Rotterdam

Shopping centre Beurstraverse in Rotterdam - © Stadsontwikkeling Rotterdam

Paris, Promenade Plantée / Viaduc des Arts: abandoned elevated train line is transformed into a attractive walk with ateliers underneath and a new park on top (1990)

Paris, Promenade Plantée / Viaduc des Arts: abandoned elevated train line is transformed into a attractive walk with ateliers underneath and a new park on top (1990)

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover more