Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Prior to the advent of the automobile, active ‘main streets’ were the centre of many towns and neighbourhoods. These mains streets were filled with human-scale sensory experiences. The invention of the car in the 20th century and new ways of transporting goods altered the design and lay-out of cities. Many cities underwent massive infrastructure changes, transformations of downtowns, and proliferation of single-function land use. Modern building design and changes in the way we shop (e.g. the emergence of the supermarket) has weakened urban shopping streets and their plinths. “The City at Eye Level” is a plea for the return of human-scale streets and for diverse and active plinths of the buildings, in order to create a dynamic and safe urban realm.

The idea of “The City at Eye Level” however is not new: many iconic urban planning thinkers have been instrumental in influencing the development of a human-scale urban planning and design in our (inner) cities. Longtime principles set forth by Kevin Lynch, Gordon Cullen, Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl, William H. Whyte and Allan Jacobs (among many others) are relevant to today’s planning. We want to give due credit to those iconic thinkers.

Kevin Lynch (1918–1984) was an American urban planner who studied at Yale and at MIT, later teaching at MIT for 15 years. His most well-known works are The Image of the City (1960) and Good City Form (1984). The first book was a 5-year research project studying the ways in which people use, perceive, and absorb the city. This book organized the city into five image elements he called paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks. He also invented the word “way finding” and many other vocabulary regularly used in planning today.

“…, this study will look for physical qualities which relate to the attributes of identity and structure in the mental image. This leads to the definition of what might be called imageability: that quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer. […]

A highly imageable (apparent, legible, or visible) city in this peculiar sense would seem well formed, distinct, remarkable; it would invite the eye and the ear to greater attention and participation. The sensuous grasp upon such surroundings would not merely be simplified, but also extended and deepened.

Such a city would be one that could be apprehended over time as a pattern of high continuity with many distinctive parts clearly interconnected. The perceptive and familiar observer could absorb new sensuous impacts without disruption of his basic image, and each new impact would touch upon many previous elements. He would be well oriented, and he could move easily. He would be highly aware of his environment.”

– The Image of the City, pp. 9–10

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City

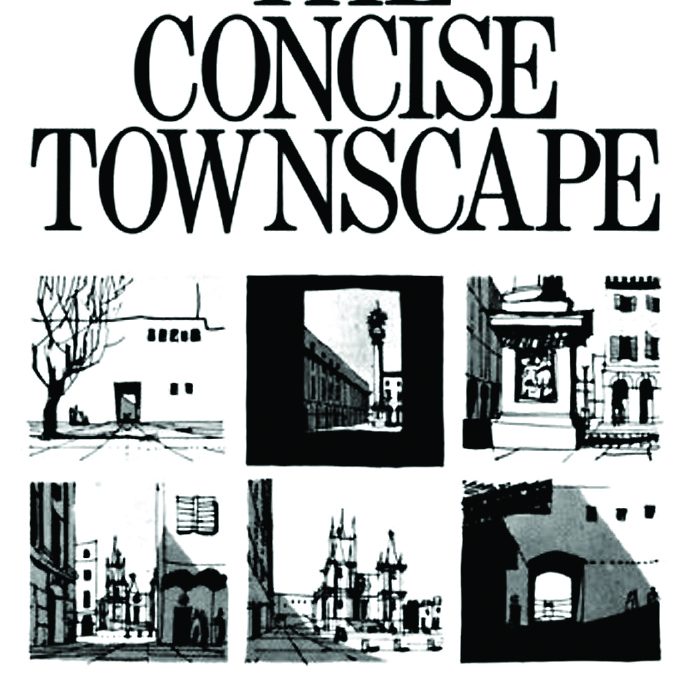

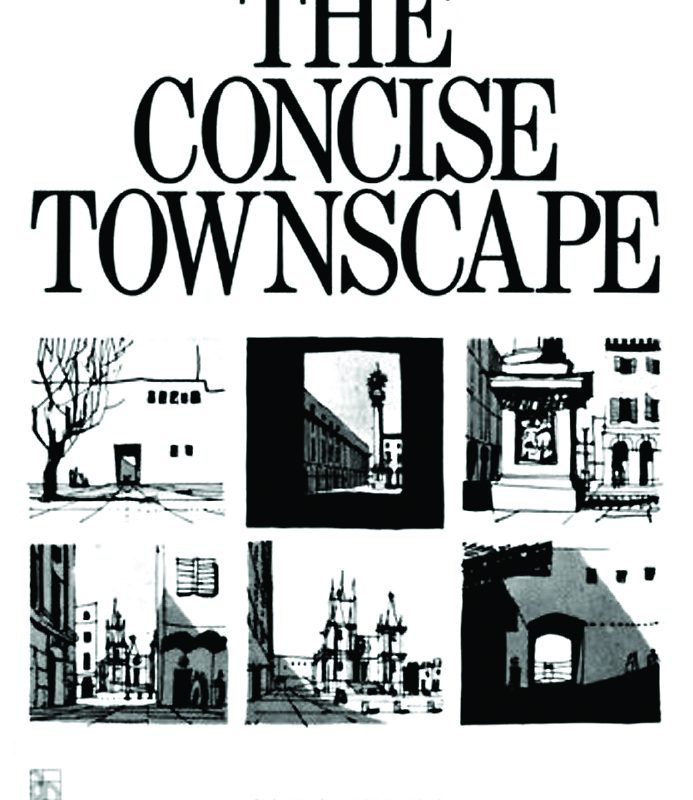

Gordon Cullen (1914–1994) was an English architect and urban designer. He developed an eye for seeing the obvious qualities in British towns. He saw that places of great beauty and strong character have been created over the centuries and are developed from the point of view of a person. He started identifying and analysing these essences of the British town and developed them into lessons for architects and planners. Gordon Cullen is best known for his book Townscape, first published in 1961; later editions published under the title The Concise Townscape (1971).

“The significance of all this is that although the pedestrian walks through the town at a uniform speed, the scenery of towns is often revealed in a series of jerks or revelations. This we call SERIAL VISION. […] The human mind reacts to a contrast, to the difference between things, and when two pictures […] are in the mind at the same time, a vivid contrast is felt and the town becomes visible in a deeper sense. It comes alive through the drama of juxtaposition. Unless this happens the town will slip past us featureless and inert.”

“In this […] category we turn to an examination of the fabric of towns: colour, texture, scale, style, character, personality and uniqueness. Accepting the fact that most towns are of old foundation, their fabric will show evidence of differing periods in its architectural styles and also in the various accidents of layout. Many towns do so display this mixture of styles, materials and scales.”

– The Concise Townscape, pp. 9–12

Gordon Cullen,

The Concise Townscape

Gordon Cullen,

The Concise Townscape

Probably one of the most famous American writers on urban planning and city economy, Jane Jacobs (1916–2006) is best known for her contributions and harsh critiques of urban renewal policies and development in the 1950s and 60s and her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). During a time when American suburbanization reigned, she was one of the few promoters of the city and city life. She fervently opposed urban renewal and many planning models of her time. Jacobs is renowned for her concepts ‘eyes on the street,’ mixed use development, and bottom-up planning. Her detailed observations of city life and function influenced urban planning in many ways.

“A city street equipped to handle strangers, and to make a safety asset, in itself, our of the presence of strangers, as the streets of successful city neighborhoods always do, must have three main qualities:

First, there must be a clear demarcation between what is public space and what is private space. Public and private spaces cannot ooze into each other as they do typically in suburban settings or in projects.

Second, there must be eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street. The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to insure the safety of both residents and strangers, must be oriented to the street. They cannot turn their backs or blank sides on it and leave it blind.

And third, the sidewalk must have users on it fairly continuously, both to add to the number of effective eyes on the street and to induce the people in buildings along the street to watch the sidewalks in sufficient numbers. Nobody enjoys sitting on a stoop or looking out a window at an empty street. Almost nobody does such a thing. Large numbers of people entertain themselves, off and on, by watching street activity.”

– The Death and Life of Great American Cities, p. 35

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Educated as an sociologist, William Whyte (1917-1999) began working as an organizational analyst. While working with the New York City Planning Commission in 1969, he began to wonder how city spaces were actually working out and used direct observation to describe behaviour in urban settings. With use of cameras, movie cameras and notebooks, he introduced new ways of urban research and described the substance of urban public life in an objective and measurable way. These observations were developed into the “Street Life Project”, an on-going study of pedestrian behaviour and city dynamics, leading eventually to the book and companioning movie The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1980). Whyte believed in public spaces as places where people and traffic come together. Whyte’s observations and ideas are still relevant for the way we use our cities and streets..

“What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people. If I belabor the point, it is because many urban spaces are being designed as though the opposite were true, and that what people liked best were the places that they stay away from. People often do talk along such lines; this is why their responses to questionnaires can be so misleading. How many people would say they like to sit in the middle of a crowd? Instead, they speak of getting away from it all, and use terms like ‘escape’, ‘oasis’, ‘retreat’. What people do, however, reveals a different priority.”

– The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, p. 19

“Another key feature of the street is retailing – stores, windows with displays, signs to attract your attention, doorways, people going in and out of them. Big new office buildings have been eliminating stores. What they have been replacing them with is a frontage of plate glass through which you can behold bank officers sitting at desks. One of these stretches is dull enough. Block after block of them creates overpowering dullness.”

– The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, p. 57

William H. Whyte, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces

William H. Whyte, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces

Allan Jacobs is an American urban planner and professor emeritus of the University of California, Berkeley. He is well-known for publications and research on urban design, as well as his contribution to the urban design manual for the City of San Francisco. He is an avid proponent of multi-modal streets that do not separate users. His comprehensive resource book, Great Streets (1995), illustrates the dynamic interaction between people and streets, and analyzes the specific attributes of these great streets.

“Great streets require physical characteristics that help the eyes do what they want to do, must do: move. […] Generally, it is many different surfaces over which light constantly moves that keeps the eyes engaged: separate buildings, many separate windows or doors, or surface changes. […] Visual complexity is what is required, but it must not be so complex as to become chaotic or disorienting. […] Beyond helping to define a street, separating the pedestrian realm from vehicles, and providing shade, what makes trees so special is their movement; the constant movement of their branches and leaves, and the ever-changing light that plays on, thorough, and around them.”

– Great Streets, p. 282

“Generally, more buildings along a given length of street contribute more than do fewer buildings. […] With more buildings there are likely to be more architects, and they will not all design alike. There are more contributors to the street, more and different participants, all of whom add interest. […] The different buildings can […] be designed for a mix of uses and destinations that attract mixes of people from all over a city or neighborhood, which therefore helps build community: movies, differentsized

stores, libraries.”

– Great Streets, pp. 297–298

Allan Jacobs, Great Streets

Allan Jacobs, Great Streets

G. Cullen (1971), The Concise Townscape, Architectural Press, Oxford UK

A.B. Jacobs (1995), Great Streets, MIT Press, Cambridge MA

J. Jacobs (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, New York

K. Lynch (1960), The Image of the City, MIT Press, Cambridge MA

W.H. Whyte (1980), The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces,

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover more