Keep up with our latest news and projects!

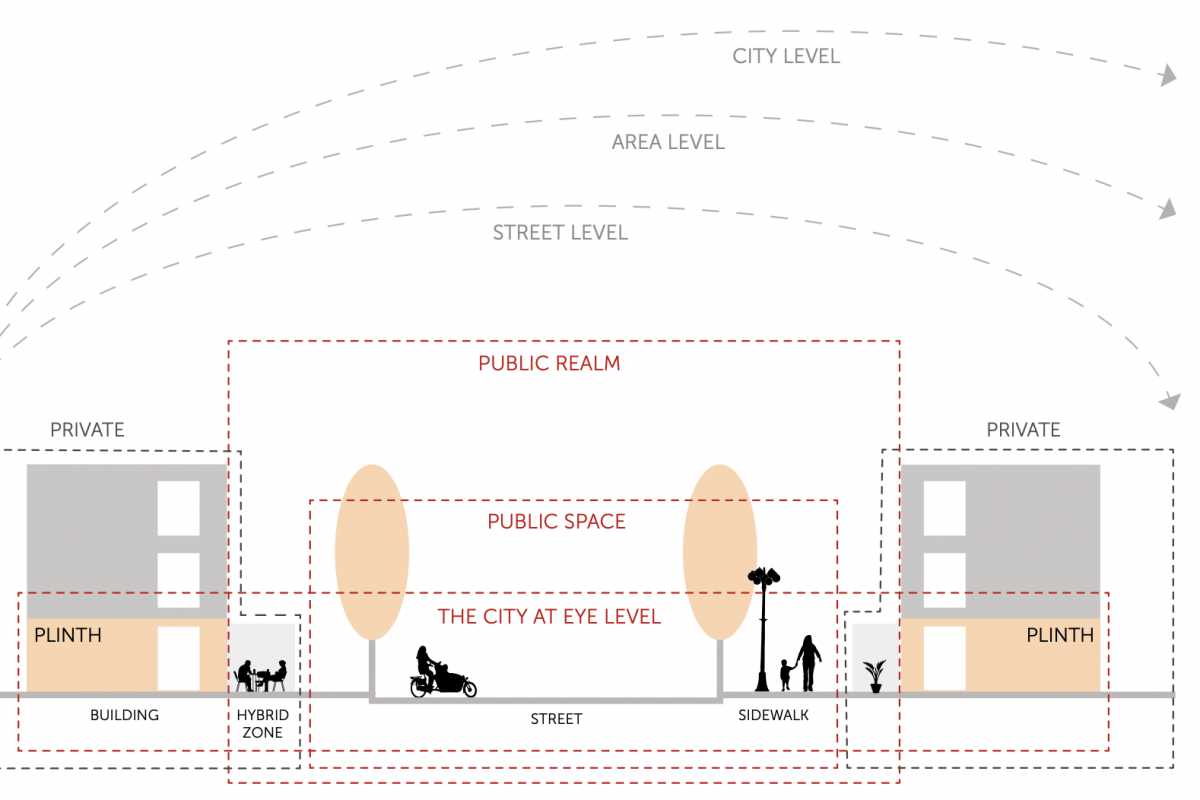

Public space is the backbone of a sustainable city. Great streets, places where you instantly like to be, human scale buildings and streets, co-creation of the public space by the users, placemaking, active ground floors and a people-centred approach based on how we as human beings experience the space around us — that is what The City at Eye Level is all about.

We all know that intuitive feeling when we really feel at home in a street, a park or a square: it is not just a public space, it is a place. With the City at Eye Level, we aim to understand the mechanisms behind that feeling. Because if we do, we can recreate these places in newly developed or in already existing parts of our cities. We can then work with the community to get from spaces to places, from liveable to lovable.

We ask ourselves: what do we as pedestrians experience when we look around? Is the street comfortable, welcoming and walkable? Do the surrounding buildings, their use, and their design makes an attractive urban environment where we feel at home? Do the ground floors connect with pedestrian flows in the urban area? Do the squares, parks and terraces function as places where we exchange ideas and encounter new, different types of people?

To understand the underlying mechanisms better, and work on strategies for change, we (STIPO, a team for urban development based in Rotterdam, The Netherlands) initiated the international program The City at Eye Level. The network was built with partners such as UN-Habitat, Project for Public Spaces, Gehl Architects, The Future of Places, Think City and PlacemakingX. With them, we generated a group of 80+ contributors worldwide and collectively wrote the book The City at Eye Level. All the lessons are open source and shared via the website.

Shops and traffic in Cheapside, London (1831).

Shops and traffic in Cheapside, London (1831).

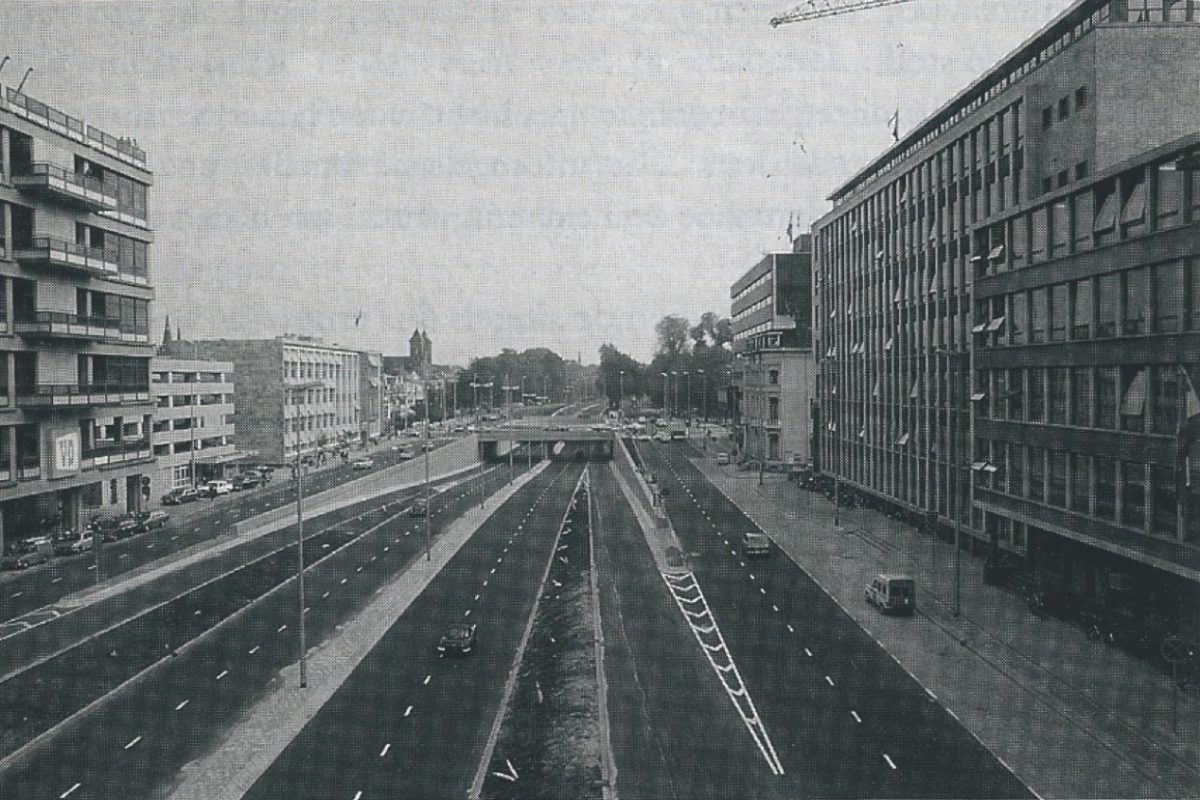

The muted Catharijnesingel-canal in Utrecht, built in the 1960s.

The muted Catharijnesingel-canal in Utrecht, built in the 1960s.

Before, we built our cities on walking distance. Everything had to happen within one hour of walking: living, working, shopping. It led to compact, walkable, mixed-use cities, that adapted to the local climate. Not because we wanted to, but simply because that was the way life was organised. This all changed in the 1960s, with the mass introduction of the car, and the modernist approach to urbanism, separating functions. Le Corbusier’s ‘Plan Voisin’ was the example: a rational high-rise model designed to replace the historic inner city of Paris. It did not get implemented there. However, it did get built in the Paris outskirts, and in so many other cities across the world throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Most cities lost their eye for a walkable, human scaled city.

This book is not meant as a plea against modernism in general, nor as a plea in favour of traditional architecture. Modernist architecture has brought about some of the most exciting buildings of our time. Modernists sought to create liveable, green, clean cities. However, modernist urban design neglected one key element: we have two parts of our brain. We want our cities to function rationally, but we also want to be inspired and to listen to our hearts. We cannot capture the city in simplified rational models only. Jane Jacobs advocated to embrace the full complexity of the city, and she made us aware of what we throw away when demolishing existing urban fabric. We stand on her shoulders now.

This City at Eye Level book, if anything, is meant as a plea to combine and enrich any kind of urbanism with human scale, with the eye level experience, that has been so often overseen in the past decades. This is why from 2014 to 2016, we worked together with UN-Habitat, Future of Places, Project for Public Spaces and many others towards a new World Urban Agenda. We advocated for a holistic, fine-grained city with human scale and a people-centred, participatory approach, and adequate public spaces for all. This was adopted in Quito in 2016, in Habitat III for the New Urban Agenda.

In the meantime, our cities have started to become more attractive to live in. More and more, our economies are based on creativity and innovation. High quality public space and interaction between people are no longer nice to have but need to have. Many cities are working on restoring the balance between pedestrians and cars. We are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of healthy and happy cities, with public spaces that invite its citizens to walk, cycle, play and engage in sports.

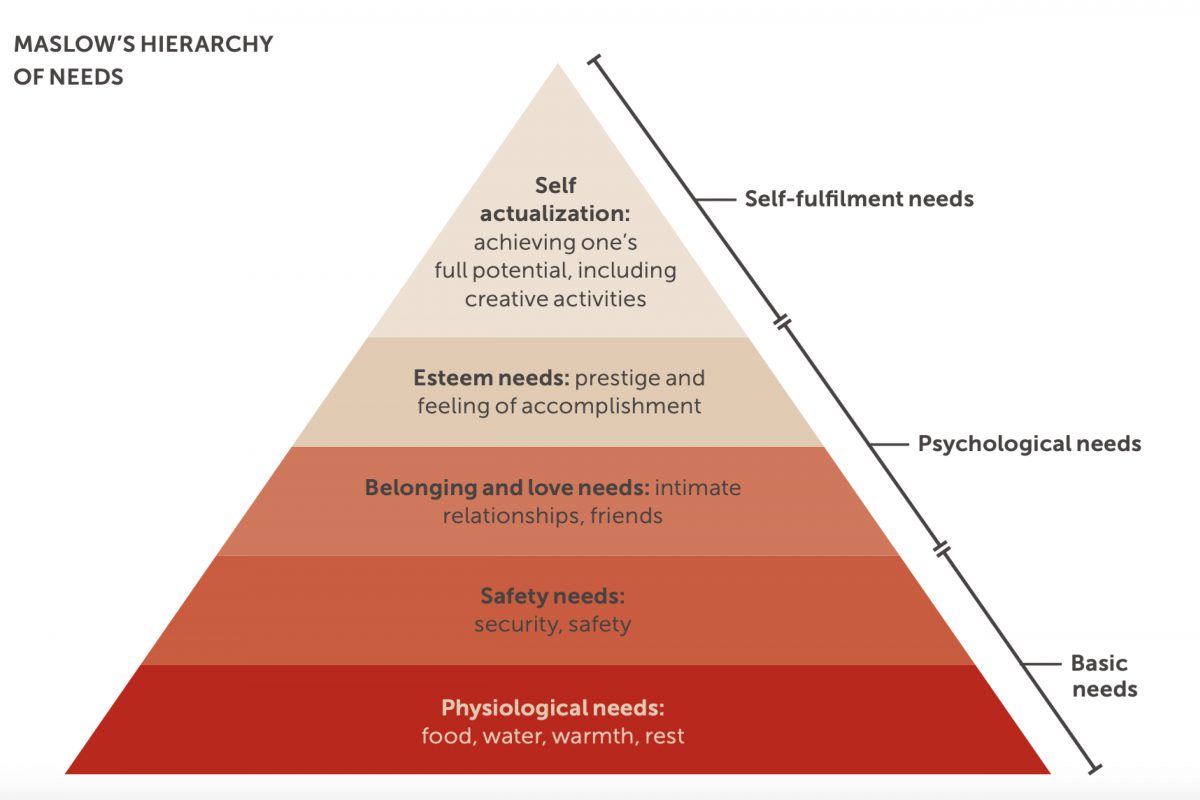

If we want to work on the eye level more, we should first dig deeper into how we, as human beings, experience our surroundings when we walk down the street. Let us dive into urban psychology for a bit and now highlight three universal aspects of how we experience:

Our frog eyes call for variety, our ears call for trees and our feeling calls for intimate spaces. These are universal values. Of course, if we want to understand the full experience, the next step should be to dive into the specific aspects depending on the local culture, the social and political relations, the local acceptance of what is decent behaviour, the local climate. These are the reasons to compose this book, specifically delving in the specific contexts in Asia. But first, we will go into the elements we can take to Asia from the international experiences.

The City at Eye Level book, fed by many insights and cases from across the world, describes the mechanisms needed to create a more human scaled city. Let us first summarise four key lessons that are a fundament for a better city at eye level in the Asian context and beyond.

Working to achieve a better city at eye level, we need to understand why we are getting so little of it in day-to-day practice. If we know which mechanisms are working against us, we will know better which issues to address in developing new strategies for our cities. In brief, we recognise at least seven mechanisms:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has,” said Margaret Mead. With the City at Eye Level programme and network, we are uncovering criteria, new approaches and methods for development, transformation and systemic change and tools to address these mechanisms working against us. Many of these can also be recognised in the contributions in this book. We see six drivers for systemic change towards developing our cities more around social life, human scale and great public spaces: