Keep up with our latest news and projects!

During the economic crisis of 2015 the municipality of Nieuwegein in the Netherlands set off to revive and develop Rhijnhuizen – a business district with a hidden historical part, a plethora of vacant buildings and some one hundred building owners. But what do you do with an area full of mostly vacant spaces and offices that look straight out of George Orwell’s ‘1984’? ‘You get rid of the offices’, most would answer, but that was not what Hans Karssenberg and Emilie Vlieger had in mind when they took on the challenge of developing the abandoned area and started the Club Rhijnhuizen.

The Club builds the network, is active in matchmaking between owners of vacant buildings and new initiatives and developers, co-creates the quality of the area, sets up placemaking to transform spaces into places, programs events and looks after area promotion and information. In three years time, the network grew from 10 to over 400 participants. One of the leading ideas is that placemaking should not be a one time intervention, but a long term and repeated investment: from place making to place management. The network supports this, but can only be sustained with enough structural funding. So what is the financial model?

Hans explains that Club Rhijnhuizen was born out of numerous meetings with local stakeholders in which they brainstormed together how to tackle the issue and create a town for everyone. To transform an area, he says, you need three things: a vision, a network and a business case.

The owners should have a business case for their own buildings and collectively, the municipality and the community, should have a business case for the entire area. To turn a district full of vacant offices into a residential area where people want to live, ride a bike or simply walk around, the infrastructure of the entire space needs to change. You need to introduce public transport, basic facilities like playgrounds and benches, as well as some nice urban vegetation.

The most interesting aspect of Club Rhijnhuizen is not even the successful transformation of the area itself, or the collective process adopted by a group of co-creators, but rather the underlying financial model.

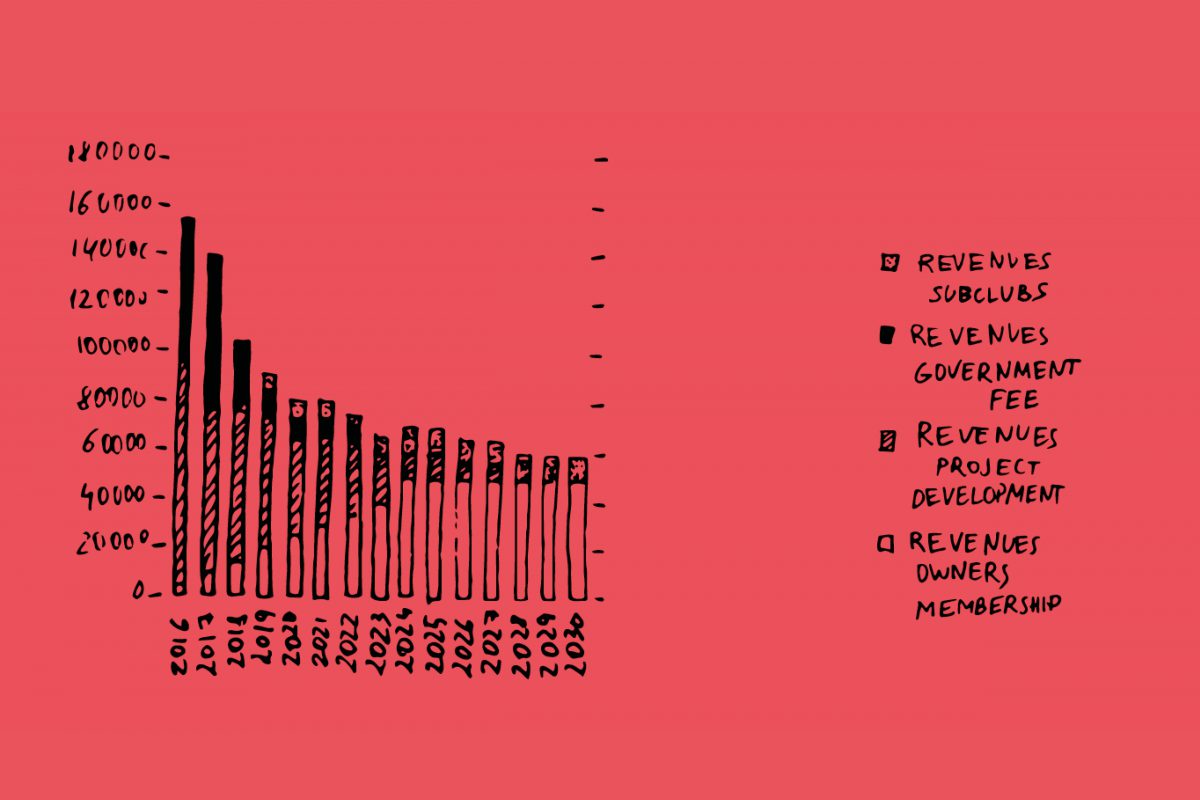

Club Rhijnhuizen was set up as a cooperative, of which building owners, residents, companies and social and cultural initiatives can become a member. All members of the Club pay an annual fee. At the same time, and this is the hybrid part of the financial model, it is compulsory for real estate developers to pay an area fee for investments into public space and common amenities. 10% of that area fee goes into the Club Rhijnhuizen. In the first six months municipal funds helped kickstart the investments, based on the mutual agreement that the support was temporary and would only be provided in the initial period. After that the Club was expected to be economically self-sustainable.

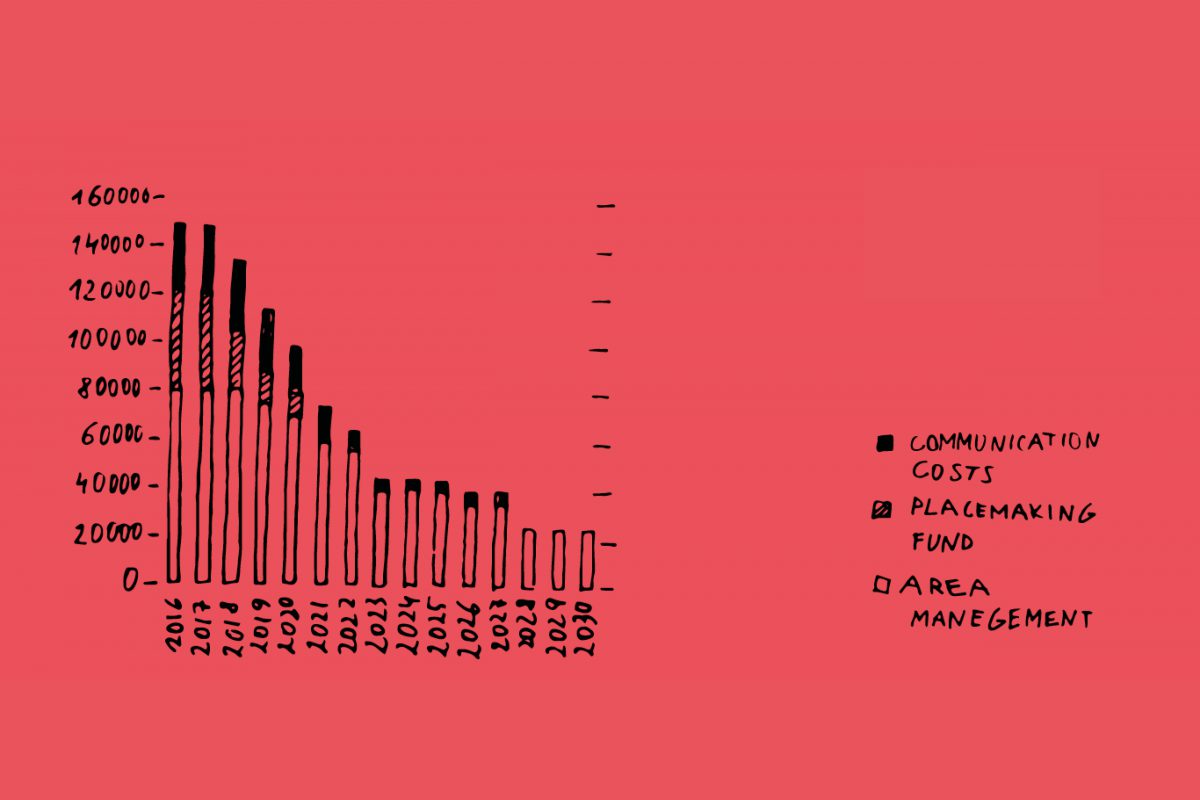

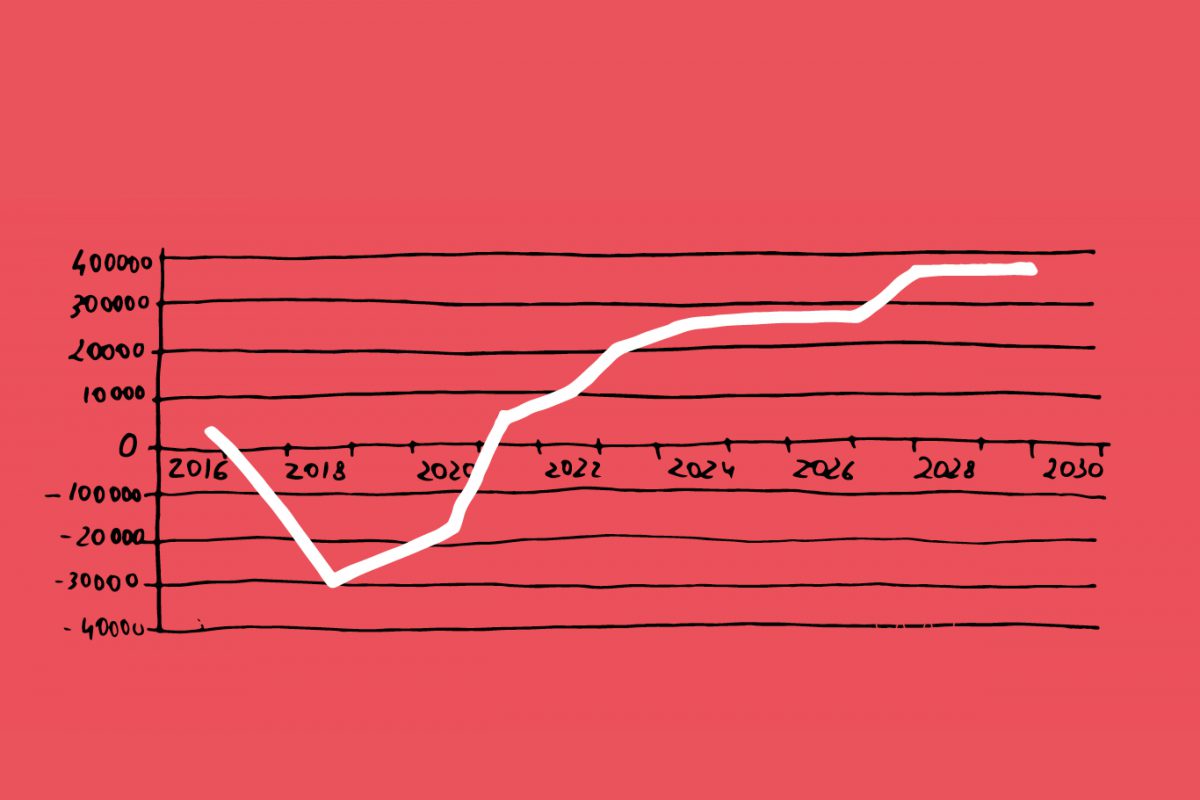

The graph below indicates how the business case was formed, and how reliance on government funds decreased while revenues went up. The model, which differs substantially from other legal and financial structures, was approved by the municipality, offering a sustainable financial scenario for Rhijnhuizen.

The fund covers the costs associated with the area management, communication and placemaking. At Club Rhijnhuizen decisions about the yearly strategy for investment are taken collectively.

With the creation of a sustainable financial model, Club Rhijnhuizen can continue to be the driving force behind the area development for many years to come. It is the collective effort of the building owners, partners, new residents and an innovative local government that made this partnership possible. And, of course, the persistent, sometimes stubborn support by outside facilitators Hans and Emilie who continued to look for creative solutions and sustainable answers.

In a nutshell, this case sets a precedent of how a solid business case can promote and sustain truly collective development. Most importantly for this book, it acknowledges that re-developing an area leads to a degree of gentrification. It also acknowledges that placemaking may increase property value by bringing more life to the area. However, it taps into the financial merits of the ones profiting the most: building owners and real estate developers. With the Club as a hybrid cooperative, they are required to reinvest a part of their profits back into the community and sustainable placemaking.

Transformation of an area has the risk of gentrification, yet with a mechanism to reinvest part of the profits back into the community we limit that possibility. This is what we like to call gentlyfication (for further reference see also the article by Theo Stauttener). The Club Rhijnhuizen is one of its kind in The Netherlands, still, but hopefully more examples will follow.