Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Does a province that has its own language also have its own form of placemaking? You bet! ‘For us, placemaking is always about mienskip’, says Harmen de Haas, director of urban planning and administration in the municipality of Leeuwarden. Many dictionaries give ‘community’ as a synonym for the word ‘mienskip’, but Haas views it as a much broader concept. ‘It means being conscious of your own culture and everyone pitching in as a team, whereby people take responsibility for their actions. Our role as the municipality is to bring people together. We view the city as a campus, and we’re building it together.’

For the Frisian capital that means never focusing solely on the city anymore. ‘These days, the emphasis in urban development is often on big cities. But smaller and medium-sized cities, such as Leeuwarden, are fundamentally different. We have a strong link to our rural areas. We feel responsible for them and depend on them, and we emphasise that in placemaking too.’

A second fundamental element in Frisian-style placemaking is fluidity – which De Haas believes is directly linked to the geography of Friesland. ‘Everyone here lives near water,’ he says. Fluid placemaking means that projects aren’t rigid but rather are open to outside influences.

A third aspect of placemaking in Friesland is that ‘places of hope’ are being created. De Haas interprets that as ‘giving desire a place’.

These elements are evident in the plans that Leeuwarden is developing for 2018, the year in which the city will be cultural capital of Europe. Leeuwarden-Fryslân 2018 (LF2018) won this desirable status with a bid under the heading ‘iepen mienskip’ (‘iepen’ means ‘open’).

Being the cultural capital of Europe presents many opportunities, according to De Haas. ‘Among other things, it acts as an accelerator. There’s a deadline with a limited amount of preparation time, which creates a sense of urgency. It also leads to a rethink and speeds up the development of projects.’

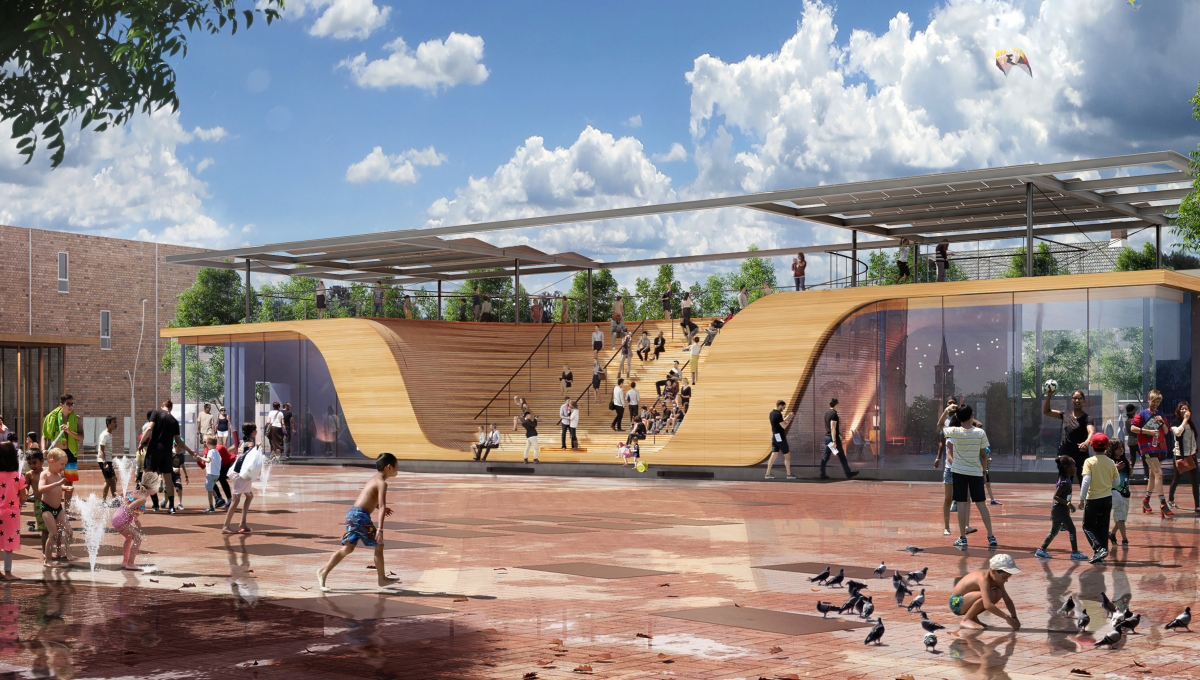

An example of the projects that De Haas is referring to is the approach of the Oldehoofsterkerkhof, the large square in the centre of Leeuwarden, where the town is situated, among other things. ‘There are all kinds of institutes there working with language. Their front doors are shut. We want to open these doors with the LF2018 event Lân fan Taal (Country of Language), by means of both physical measures, such as language pavilions, and programming about multilingualism. And mienskip plays an emphatic part in this programming.’

Day view, OBE

Day view, OBE

Pictures of new station area and fountain Plensa - © Gemeente Leeuwarden

Pictures of new station area and fountain Plensa - © Gemeente Leeuwarden

One of the language pavilions is the TaalExpo. The aim of this expressive construction is to enliven the Oldehoofsterkerkhof the entire year round and act as a grandstand during events that already frequently take place on weekends.

Another example are the sculptures of Spanish artist Jaume Plensa. The municipality wanted to reinvigorate the station area. The initial idea was to install a fountain there. But Plensa didn’t think it was a good idea to have a fountain in a city with Leeuwarden’s climate. He preferred images surrounded by mist. He believes that they complement typical Leeuwarden institutions, such as the renowned international water technology institute Wetsus, which is located near the station on the ancient urban river Potmarge.

The inhabitants of Leeuwarden welcomed Plensa’s idea. The only people who had objections were traffic engineers and urban planners. ‘More than anything,’ De Haas says, ‘I think they need to get used to the new way of working. But we persevered with the sculptures, and ultimately they helped us to make it possible. The traffic engineers and urban planners could be a little less dominant though.’

The new way of working that De Haas is referring to prioritises ‘inviting’. ‘We’re good at that as a municipality. We believe that we need to engage with the different parties, parties that have the drive to improve the city and province. We take the initiative and invite people to come up with ideas. But if they do approach us, then they have to be willing to take action. In fact, we always ask them: are you here on your own or on behalf of something else? Ideas have to be a part of the mienskip. So if you have a plan, you have to mobilise support yourself.’

The Frisians have a long tradition of cooperation, though that way of working is sometimes perceived to be slow-going. De Haas acknowledges that decision-making sometimes goes at a snail’s pace, or as the Frisian’s say ‘op zijn elfendertigst’ (at eleven and thirty). This expression can be directly traced back to Friesland. Apparently it refers to the slow manner in which the States of Frisia, consisting of representatives from 11 cities and 30 ‘grietenijen’ (the administrative districts of the public prosecutors), deliberated. ‘The drawback of relying on cooperation is that sometimes it doesn’t go beyond business as usual,’ De Haas adds. ‘We’ve been breaking with that here and there in recent years, because the will is there.’

The municipality is trying to move away from the custom of arranging everything formally. It is deliberately relaxing regulations. Art and culture are playing a remarkably important role. When Leeuwarden develops a new area on the outskirts of the city, the municipality will first give it a temporary use, in the form of theatre or music, for example. Art also serves as an alternative for expensive urban development interventions. The artist Giny Vos reinvigorated an alley, for example, by hanging the skeleton of a whale over it equipped with LED lighting.

One part of mienskip is that the authorities create space for people. As an example, De Haas cites the cooperation with shopkeepers. ‘They often claim public space, because it’s part of their display window. Authorities are quick to think: we have to intervene. We’re doing things differently, however. We let the shopkeepers arrange and rectify matters. One is example is when they put benches down somewhere to liven up the street. We give them that space. Because you can easily mess up the mienskip by acting strictly.’

Kening fan 'e greide - in the middle of the space

Kening fan 'e greide - in the middle of the space

Another example of mienskip, in which Leeuwarden and its surroundings figure prominently, is the Kening fan ‘e Greide (King of the Meadows) project. Its aim is to preserve the quality of the landscape. Scientists, farmers, musicians, communication people and others are working together on this project. Using the black-tailed godwit as its symbol, the project addresses major issues regarding ‘landschapspijn’ (a newly coined phrase meaning ‘landscape pain’), biodiversity and nature-inclusive agriculture in such a way that it also affects the city and its inhabitants. The project recently won the Anita Andriesen Award for spatial quality for having brought attention to ‘the discussion about the quality of the landscape in Friesland and beyond’.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover more