Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Collectively shared spaces are possibly the most underrated spaces when it comes to inclusive neighbourhoods. Think of the potential of all the stairways, porticos, shared entrances, courtyards and elevators. They’re chronically underused, mainly because of their design and layout. In general, they are places where neighbourhood residents don’t feel at home. They usually don’t even consider these places to be part of their neighbourhood. This article shows how such attitudes can be turned around. It also explores the role collectively shared spaces can play in creating inclusive networks in neighbourhoods and stimulating residents to become more active in their community.

It started about ten years ago in a neighbourhood in Zaandam, called Poelenburg. During a conversation about feeling at home with a resident living in one of the apartment buildings, she mentioned that in the last five years or so, she had become more and more reluctant to leave her home. She basically had two choices left. The first was to go out to the supermarket, ignore everyone on the street, and return home as soon as possible. The second choice was to take her car to visit family or friends outside of the neighbourhood. This meant going straight from the front door to the car and back. As soon as she slammed her front door shut, she felt completely safe again.

Neither of the two choices did any good to how she felt at home in her own neighbourhood. She went from being a real neighbourhood person to someone avoiding the neighbourhood. The reason for that was plain. The composition of residents in Poelenburg had changed. A fast-growing group of residents with a different background and a different mother tongue had moved in. Now, when she walked the streets of Poelenburg she couldn’t understand what people said. It made her feel less and less accepted in the local social networks. She didn’t belong anymore.

When she felt she could no longer connect to her new neighbours, her response was to pull back into her home and redecorate it together with her husband. From the inside they turned it into a palace. From the outside her home became a fortress. The portico or collectively shared stairway played an important role in this. The changes in the neighbourhood had first become visible there. The portico connected eight homes to a shared stairway. It wasn’t considered a place to meet neighbours, let alone chat with them. Most of the time when neighbours met there, they shyly said ‘hi’ and kept walking in a steady pace.

This is a pity, because these collectively shared spaces can be a buffer to the outside world. A safe haven for neighbours to meet, get to know each other and get familiar with other people’s habits, beliefs and values. These places provide the opportunity for casual social interaction and through that the development of public familiarity. This means people get a chance to see neighbours who are different from them, to possibly chat and to adjust their views and expectations of the other (Blokland, 2008).

A great example of how this can work is the story of a friendship between two neighbours. Both of them lived in the same apartment building in a neighbourhood in the south of Rotterdam. One of them had lived there for about ten years and knew everything there was to know about the neighbourhood. The other had just moved in a year ago. Her apartment was still a bit bare and empty. She didn’t have a carpet on the floor, she was clearly missing closets and cupboards and had an improvised table in the living room. There was some decoration, but not much. Nevertheless, it felt homely.

To her this home represented a new beginning. After an ugly break-up she was forced to move out in a rush, together with her daughter. While she was moving the little stuff she had, into her new home, she met her neighbour. This neighbour was refurnishing her home and moving out an old couch. While taking the couch down the shared stairway the two women met and there was an immediate spark. Together they ended up moving the couch and some other furniture into the apartment of the ‘new neighbour’. This accidental meeting in the portico was the start of their friendship and defined how they both felt at home in their neighbourhood.

These examples teach two lessons. First, that collectively shared spaces are important for social networks in neighbourhoods. They mainly contribute to casual and accidental meetings between neighbours, which can be an important stepping stone to building inclusive communities. Unfortunately, this quality is usually underestimated, which means housing corporations and residents rarely invest in improving collectively shared spaces. Going back to the two neighbours in Rotterdam, neither of them felt comfortable enough to take ownership of the portico. One of the neighbours actually said she didn’t put out her Christmas decorations because she was afraid it would get stolen. The housing corporation actively prevented ownership due to fire-department regulations. All of this keeps porticos from fulfilling their social function.

The second lesson says that porticos are the linking pin between home and neighbourhood. They’re part of a network of ‘home places’ – places where people experience a sense of home. Important to this network are the sense of trust and control. When the trust in others decreases, it becomes more likely that a place will fail to evoke a feeling of home and is removed from the network. The other way around is that, through interaction with others, a sense of trust is created and a place is added to the network. The bigger the network, the stronger people’s feeling of home. Equally important is the sense of control. The more control, the more a person feels he or she can define a place. People feel more at home in places where they experience control and thus ownership. Some places evoke more control than others, of course. A distinction can be made between a ‘heaven’ and a ‘haven’ (Duyvendak, 2011). The first are places where people experience a great sense of control, which provides safety and comfort. In the latter, people experience less control. They might still take ownership and feel safe, but these places are also used by others and therefore defined by social interaction with others.

The portico can be a ‘haven’. It forms a link between the home and the neighbourhood, between heaven and haven. The fact that many porticos don’t function this way has everything to do with their design. When a Dutch housing corporation asked Stipo and Thuismakers Collectief to work with residents on their porticos, it provided a great opportunity to explore how porticos can increase residents’ feeling at home.

As a multidisciplinary team we were eager to learn more about the social potential of porticos. So, besides from working with residents, we also tried to measure the impact of our interventions. We ended up doing research in twenty porticos, of which sixteen were the control group where residents only filled in a questionnaire. In the remaining four porticos we extensively worked with residents, starting with interviews about each resident’s feeling of home. In the end we talked to nearly all thirty-two residents. Our analyses showed that the porticos were made up of four different zones, each with its own sense of comfort and safety. Starting with the zone at one’s front door, which was the most private area suitable for taking ownership, and ending with the front door of the portico itself, which was the most public zone suitable for casual social interaction and collective ownership. The zones in the middle were transition places between the private and the more public zones.

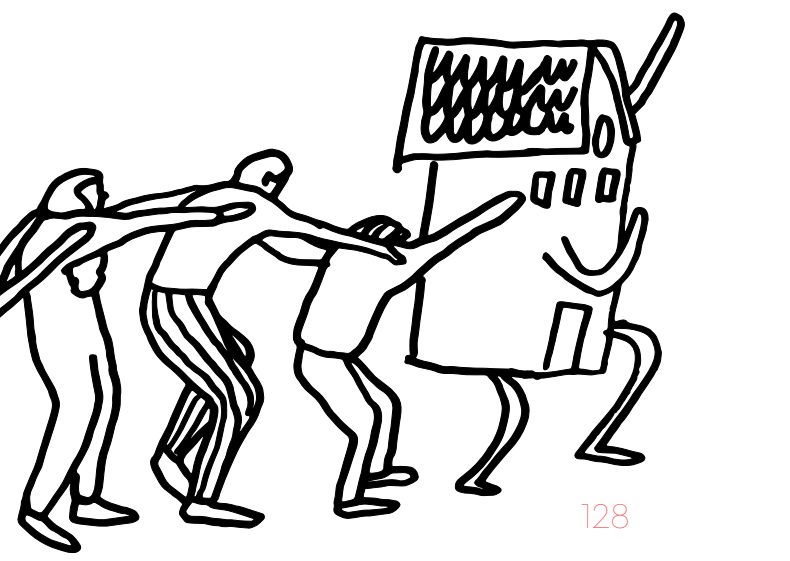

The idea behind our work was to create the conditions for residents to take ownership of the portico, both individually and collectively. This included providing places to discuss design options, such as color, material, and other spatial interventions. It also included a temporary living room in the portico where people could sit, meet, eat and talk. In the living room we made strawberry-rhubarb jam. We gave a jar of jam to each resident and asked them to name what’s most important for them to feel at home in the portico. After we heard the community’s preferences, a designer worked out a first design for the portico and presented it to the residents in the portico living room. What followed were many great discussions with residents on how to improve the existing design. Based on these discussions, the designer made a second proposal and presented it once again to the residents. This iterative process continued until the neighbours were satisfied.

To our team the design process was an excuse to bring people together, not once, but multiple times. The result was a more connected group of neighbours. Sometimes they would meet outside of the scheduled sessions and welcome new residents. When the portico was finished they started to use the space differently. For example, one of the residents started collecting clothes for donating to neighbours who couldn’t afford to buy new ones. She stored these clothes in the portico, something that was unthinkable before the design process took place. It wasn’t surprising that the analysis of the research data showed a great improvement in many aspects compared to the control group. People felt significantly more at home in the portico, knew more neighbours and felt they could rely on them more. They also felt safer, they had become more active in the neighbourhood, they were more trusting towards others, and had a more favorable view of institutions, such as the municipality and the housing corporation. Most importantly, it showed that investing in collectively shared spaces with residents restores the link between home and neighbourhood, which leads to greater involvement and more inclusive behavior.

In this project we worked hard to go beyond participation. This was difficult at times, because people felt distrustful and were convinced things couldn’t change for the better. During the project the mindset shifted from mere participation to active engagement with fresh ideas. The conversations between residents in the temporary living room inspired renewed energy and taking collective ownership of the shared space. This required small steps, that became bigger and bigger over time. In the end, the biggest win was that the portico had become part of the network of home places again, where people felt at home, together.