Keep up with our latest news and projects!

How to make the inner city of Rotterdam a place to meet, to stay and enjoy for everyone or how data can help make the inner city more attractive for all.

Rotterdam is a typical Inner City for Dutch standards. The urge to modernise has played a role in the city development for over 100 years. After the bombing in WWII, the Inner City was rebuilt in a modern style. The new Inner City, following the American model, was designed with broad boulevards, separate space for functions and, for the Netherlands, new building typologies were introduced. This plan served as the blueprint for rebuilding the Inner City until 1985 and its consequences are visible in Rotterdam until today. This fact is important to understand, that the challenges faced by the Inner City of Rotterdam are different than those of the average historical towns in the Netherlands. At the same time, Rotterdam struggles with the same ‘soft’ problems as any Inner City: how to keep it attractive for people who live, visit and work here, what to do with ever rising real estate prices, the transformation into a place-to-be instead of a place-to-buy, the bustling liveliness of a city versus the need for quiet places for those who are in search of rest, etc.

In 2008 the new plan for the Inner City was launched, called ‘the Inner City as City Lounge’. This plan was not shaped around physical interventions (like the former ones), but shaped around the soft themes. The ‘City Lounge’ was the concept of a place to stay, meet and be entertained. This was a huge shift in the way people thought about the Inner City. A place where almost no one lived, people experienced it as a concrete jungle, which lacked events and culture and was only busy during shop opening hours. Important goals underneath this plan were densification of the Inner City with housing, more and better public spaces and a new balance between cars, bikes and pedestrians. The main question was how interesting this was for the main users and if they shared the same values towards the ‘City Lounge’ goals. Three main groups can be identified.

The new 2008 plan was a game changer for houses in the Inner City. It changed the course drastically to add more inhabitants and mix them within the Inner City. The plan in 1946 foresaw 10.000 new homes. The new ambition was set for 45.000 homes. To have a more balanced population, these new homes were aimed for people with middle and high range incomes. This does not sound like an Inner City for all, but keep in mind that almost 40% of all houses within the boundary of the Inner City are already social housing (max rent €635). This percentage goes up dramatically if you add the neighbourhoods directly around the Inner City. If you look to the household composition in 2018, 60% are single-person households, 22% are 2 person-households and 15% family households. These numbers have remained pretty constant over the last 20 years. Most of the people (ca. 40%) who live within the Inner City are between 20 to 40 years old, but there are also more than average numbers of elderly people compared to other cities (approximately 15%). The biggest influx comes from middle-income people and the biggest group that leaves are families. On average 75% of all households live less than 10 years within the boundaries of the Inner City.

The plan in 1946 prioritised the city as a place to facilitate work. Today this translates to an Inner City where 27% of all the jobs in Rotterdam are located. This number is still growing every year. There are certain sectors that traditionally find a place outside the old city centres, but are well represented in the Inner City of Rotterdam. The financial sector is the biggest employer, followed by the medical cluster. The SME, normally the biggest sector in Dutch Inner Cities comes in third. Also, the last couple of years there is a major influx of freelancers and people with short-term contracts. Altogether this adds up to approximately 120.000 people who work in the Inner City every work day.

Visitors are divided into several groups. The biggest group, ca. 40.000.000 visitors, are those who come for shopping. Mostly these are people from Rotterdam and the surrounding region. Tourists make up for 1.100.000 visits every year and are growing rapidly (14% increase last year). Next to these visitors there are also 100 events and festivals hosted in the Inner City (partly) in the public spaces, aiming at local residents. The average time spent in the inner city has risen spectacularly by 10% (over 4 hours).

Knowing the users of the Inner City beyond the categories and numbers described above is important. Every intervention done to accommodate these categories is equivalent of hoping it will work. In 2008 we took motives for being in the Inner City as the leading principle. This resulted in 7 archetypes. These archetypes are responsible for over 60% of all visits, without the classical approach of inhabitants, workers and visitors. For every archetype you can ask questions like: Where do they come from, what are the triggers for these archetypes, how to approach this archetype, which time of the day they use (parts of) the Inner City, etc. An example of an archetype is ‘the cosy family’. This archetype is responsible for 14% of all visits and has a strong focus on shopping and cultural amenities like the Maritime Museum or Pathe (movie theatre). They use the Inner City mostly during the day. Best way to reach them is by local papers. They are drawn to family events, good parking, and activities that are affordable for a group. This archetype can be seduced with kids activities, popular chain stores, an informal approach and discounts for eating, shopping or parking. There is a way to translate this information into maps (day and night), which result in a heatmap per archetype with locations, streets used and time spent.

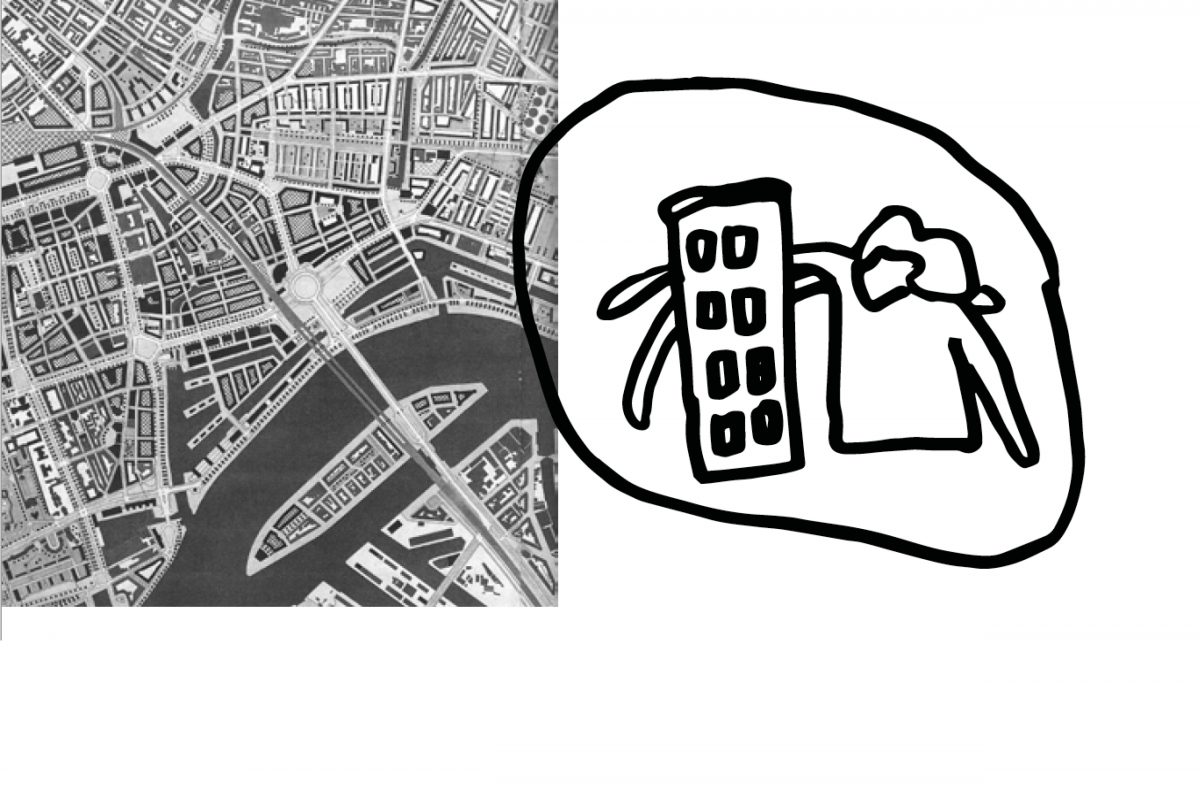

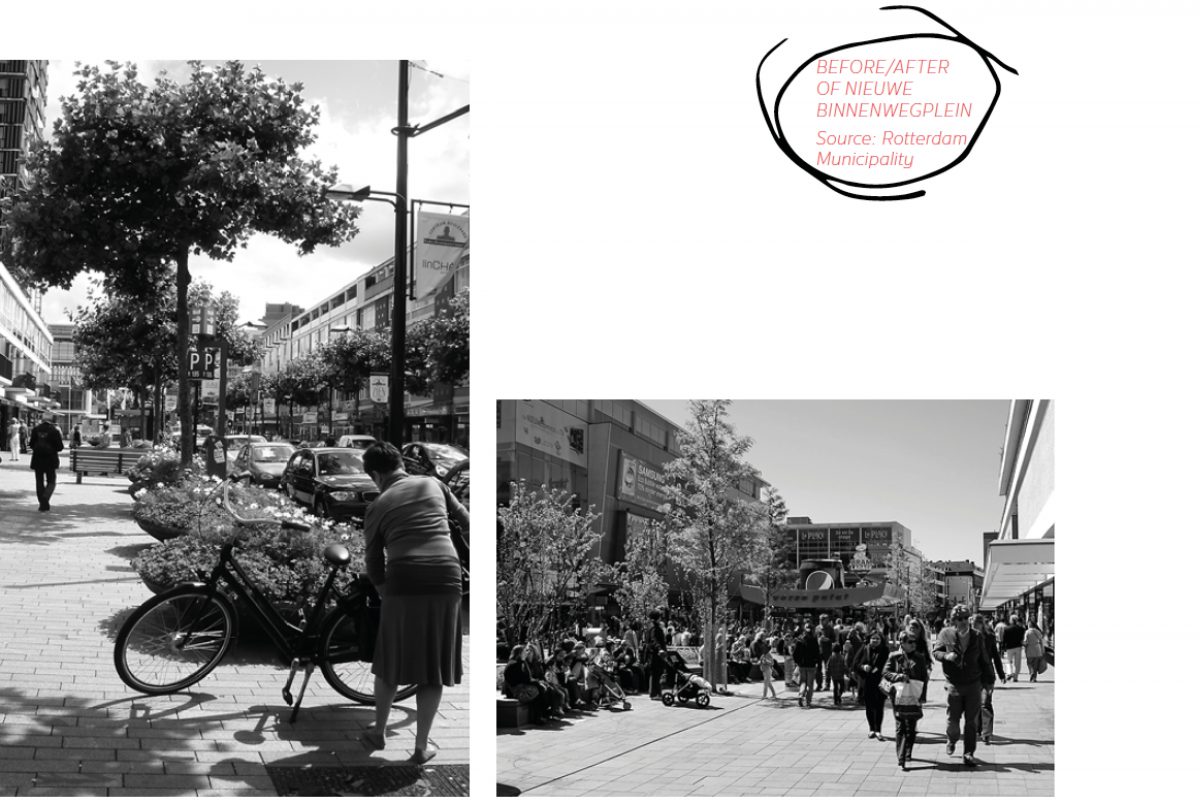

The ‘City Lounge’ essentially is a place where you want to be. First numbers showed that the average time people spend in the Inner City was short in comparison to other cities (study F. vd Hoeve, TU Delft). People who visited by car stayed approximately less than two hours, the total average was below 4 hours. This was not the duration that fits an attractive city. The target was set to prolong the time spent in the Inner City. In order to do this, a monitoring system was needed to track and follow flows of people 24/7. It measures the number of people, time spent in the Inner City, which routes are most frequently used, which places are being visited the most, and what the point of entry is for these flows. This information, combined with the data collected for archetypes and motives, enabled the creation of a strategy, executed by several programmes. ‘Connected’ city was a programme which made huge investments in public space. A lot of iconic places were redesigned into more pleasant spaces with spots to sit, more greenery, and less car use. This programme also focussed on the plinths of buildings. By making a plinth strategy for the Inner city (city at eye level), rules have been introduced for new and existing buildings in order to stimulate more interactions between pavement and building functions. The programme was focused on places and streets who were used the most. Flow monitorization provided the much-needed input to shape this programme. Through a programme called ‘liveliness and hospitality’, emphasis was put on training taxi drivers and hotel staff on how to be more hospitable, a new wayfinding system for the Inner city, temporarily programming for the public space, city marketing, etc.

But knowledge of different city visitors’ motives, investing in public space and focusing on liveliness is not enough. There are some key ingredients to make this work. First you need a monitoring system. This helps you invest every euro in a place you know people are using. This tells you exactly the difference between the day and the night time use of the Inner City and what streets and squares are activated during these times. Second ingredient is testing and experimenting. City planning usually works through extensive processes which will take years to complete and require substantial investment. You might also say they bring about irreversible results, which traditionally leads to an elaborate participation process in which different opinions are expressed and not all can be honoured. Doing an experiment, before a process like this, together with all stakeholders to first test if the proposed intervention works can be extremely helpful. This way of thinking has led to many experiments. They are small and temporary, but by using the monitoring system during and after, the result becomes visible. If the experiment was a success, the final transformation (via the traditional city planning process) was launched. If the experiment failed, we went back to the drawing board to see what could be tested differently.

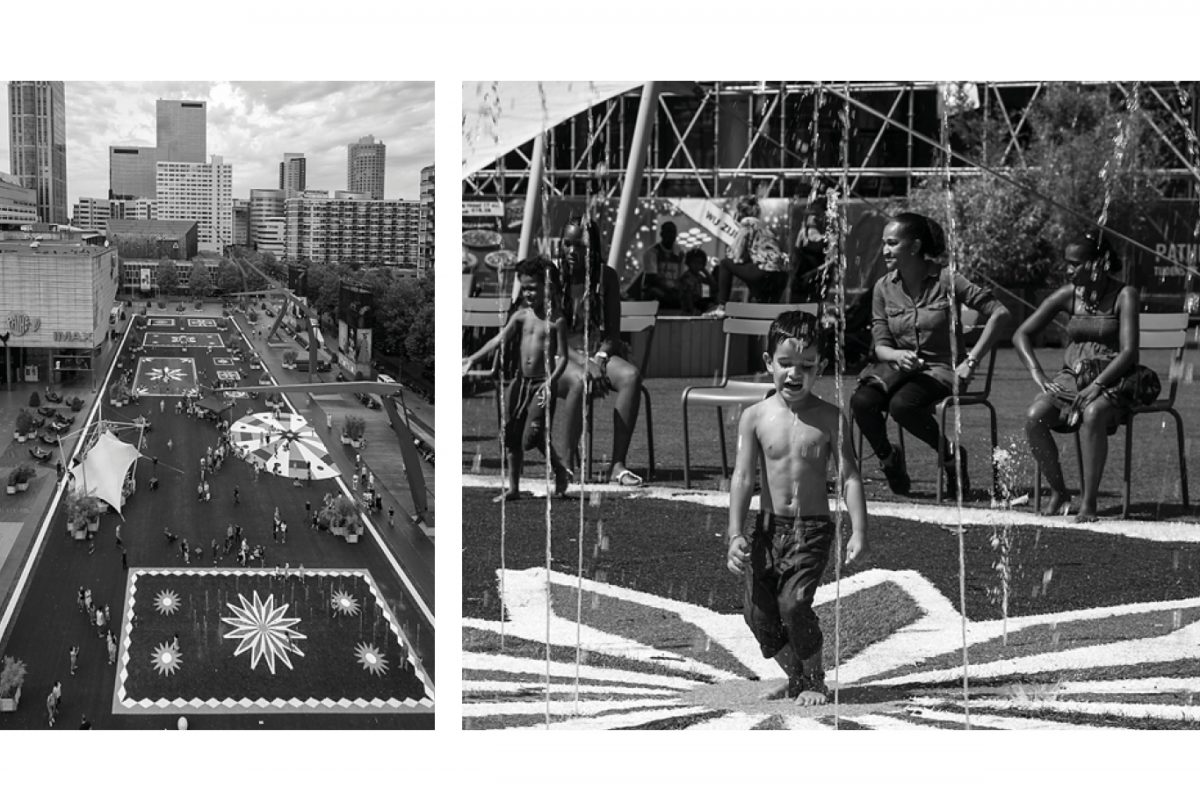

An example of an experiment is the ‘flying grass carpet’ on the Grote Kerkplein. This square had formal appearance with a couple of benches, a lot of paved surfaces and some trees. The experiment involved adding more greenery, more room for playing and informal gatherings. The square was covered with a big piece of artificial grass with some markings in the form of lines and shapes in different colours (as a way for children to play on it). On the grass a sandbox was placed and real plants in pots. The monitoring system showed a spectacular discovery. The square was used twice as much as before, and the time spent on the square had tripled. It was also used by several groups during the day. As a quiet place to eat, play and relax in the Inner City. During the experiment people were asked why they came to the square (among other things). The most surprising answer given multiple times was the fact that there was a quiet green space free from traffic where children could play. This was mentioned by people who lived close by in small apartments without a proper balcony. This experiment showed the potential of a green spot, with more seating arrangements and things to play with. The final design was made along those themes and now the square has real grass as well as more and better plants. The data from the monitoring system is even more promising. The success of this experiment led to another much bigger ‘flying grass carpet’ on the Schouwburgplein and with (for now) similar results.

Another example of an experiment (nonphysical) were the ‘010-Goodiebags’. These bags were handed out by the main parking garages in the Inner City. The idea behind these bags emerged from the monitoring system which showed that people in cars spend roughly 2 hours in the Inner City and on average do not walk more than 400 meters from their car. The bags contained coupons for free coffee, discount in certain shops, a map of the Inner City, focussed on the things we know these archetypes like. To use these coupons, you had to walk much further to another part of the Inner City form the specific parking garage where you got the bag. This tested the willingness of people to walk to places they usually did not visit and to walk more than 400 meters. Both objectives proved successful. ‘010-Goodiebags’ is now part of the weekly routine of projects being organised in the Inner City.

The two examples showed that with small precise interventions today, you can contribute to more extensive and major transformations tomorrow. In conclusion, the Inner City of Rotterdam is more than ever a place for everyone. The goal is to continue exploring the right balance between expensive and long processes and a short-term experimental programme to test interventions. Also to work with stakeholders on what their ambition could look like and testing the long-term processes. It comes down to knowing who your key users really are, knowing what they (dis)like and putting in place a monitoring system which proves your experiments and shows where people are at all moments of the day. Most importantly, these experiments should be done with entrepreneurs, residents and other stakeholders in the Inner City. This way of working increased the willingness of all involved in the Inner City to collaborate and make a change through the adventure of an experiment. In the span of 10 years, the Inner City in Rotterdam has become a better and more beautiful place, a place with a lot more users and visitors; a place where the accent shifted from ‘build more’ to a place where you want to be. There is still work to be done, but the first conclusion is that the ‘City lounge’ has been accomplished.