Keep up with our latest news and projects!

In the urban debate one fact is shared more often than any other: in 2050 80% of the world’s population will live in cities. This massive wave of urbanization is going to threaten the liveability and sustainability of the world’s cities (Mckinsey, 2016). Without a doubt, their inclusiveness will also be at risk.

However, focusing on the growing cities of the future creates a serious blind spot, and that is shrinkage. In Europe, one could almost say that for every growing city there is a shrinking one, and a few dozen shrinking villages. This case study demonstrates that shrinkage deserves our attention, and that it is a serious threat to the inclusiveness of our society.

In the spring of 2017, I conducted a research study on shrinkage and its effects on the Spanish region of Asturias. During my stay there, I saw first-hand the vast impact of shrinkage and how it affects the minds of the people wrapped up in it.

Asturias is a mountainous region in the north of Spain. It is known mostly for its natural reserves and beautiful coastline. The region is sparsely populated except for the three central cities of Avilés, Gijón and Oviedo. The region currently has slightly less than one million inhabitants, some 60% of them are concentrated in the central cities.

The region of Asturias has struggled with shrinkage for decades. Its rural towns have been losing population since the 1940s, and since the 1980s the entire region has lost around 100 000 people. According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics the region will lose another 100 000 in just over half that time.

The process began with a decline in the rural economy caused by the introduction of the European market. This put the small traditional Asturian farming industry in direct competition with the agricultural giants of Northern Europe. The mountainous landscape of Asturias prevented the farming industry from implementing modern techniques. As a result farming has declined and the rural population has more than halved.

In the 60s and 70s, the Asturian population suffered another hit, when the region’s large coal mining industry entered a crisis (Prada Trigo, 2014). Large swaths of the region’s workforce were laid off and dozens of coal mines were closed. This was one of the region’s most turbulent periods, filled with violent clashes between miners and the government. Coal mining has now all but died out in Asturias.

The combination of these two waves of decline is now causing a third one: out-migration and aging. According to Eurostat, Asturias currently has one of the fastest aging populations and lowest birth rates in Europe.

Shrinkage has had a substantial impact on the life of many Asturian cities and villages. It has been more that a mere demographic transition, but rather a fundamental change in regional landscape with severe consequences for the local social networks.

Ghost towns have become a common sight. The region now counts more than 600 abandoned villages. Here the downward spiral of shrinkage is felt hardest. Local governments have to make do with increasingly less income from taxes. This makes it almost impossible to provide people in the villages with services and to protect the environment. The effects of shrinkage are reaching further than just the buildings. Continuous neglect of the countryside has given rise to various environmental problems such as forest fires and soil degradation. This problem exacerbates when the more vulnerable elderly population is left behind, while the young make their way to larger cities.

In recent years there has been some renewed activity in the mountain areas of Asturias, mainly in the form of eco-farming. However, due to the impasse of the local governments (which are down on manpower and resources) support for such initiatives is non-existent. As one interviewee told me: “a couple of friends of mine tried to get permits to start a farm, but they had to wait for so long that they decided it would be quicker and more profitable to start growing cannabis instead.”

In the former mining cities of Langreo and Mieres life is not much better. The landscape there seems identical to the one we’ve seen in images from Detroit city. Half-dismantled factories and overgrown railway tracks give a sense of deprivation. Since the economic restructuring of the 1970s thousands of people have left these towns, vacating many houses and estates. The remaining population consists of former mine workers who are living off their state pensions.

Interestingly, the regional government has made several attempts to reignite life in these towns. With the help of European funds they have relocated part of the regional university to Mieres, hoping that the student population could revive the town. But as one of the university professors told me, “this has never really worked, all the students come by bus, they live in the big cities.”

Even in the larger cities, Avilés, Oviedo and Gijon, the effects of shrinkage are starting to show, especially on the periphery, where one can find vacant apartment buildings and abandoned construction sites. These places are a reminder of the period when planners still imagined that population growth might come back to the region. The dynamic of out-migration also works on a neighbourhood scale. Younger more mobile families migrate from the periphery to the centre of bigger cities, leaving the elderly population behind.

Shrinkage has clearly had a disproportionate effect on poorer communities and people in not-so-favorable circumstances, especially elderly citizens who are typically left behind in smaller towns and on the peripheries of cities. Despite attempts from the local planning agencies, little has been accomplished to improve their lives.

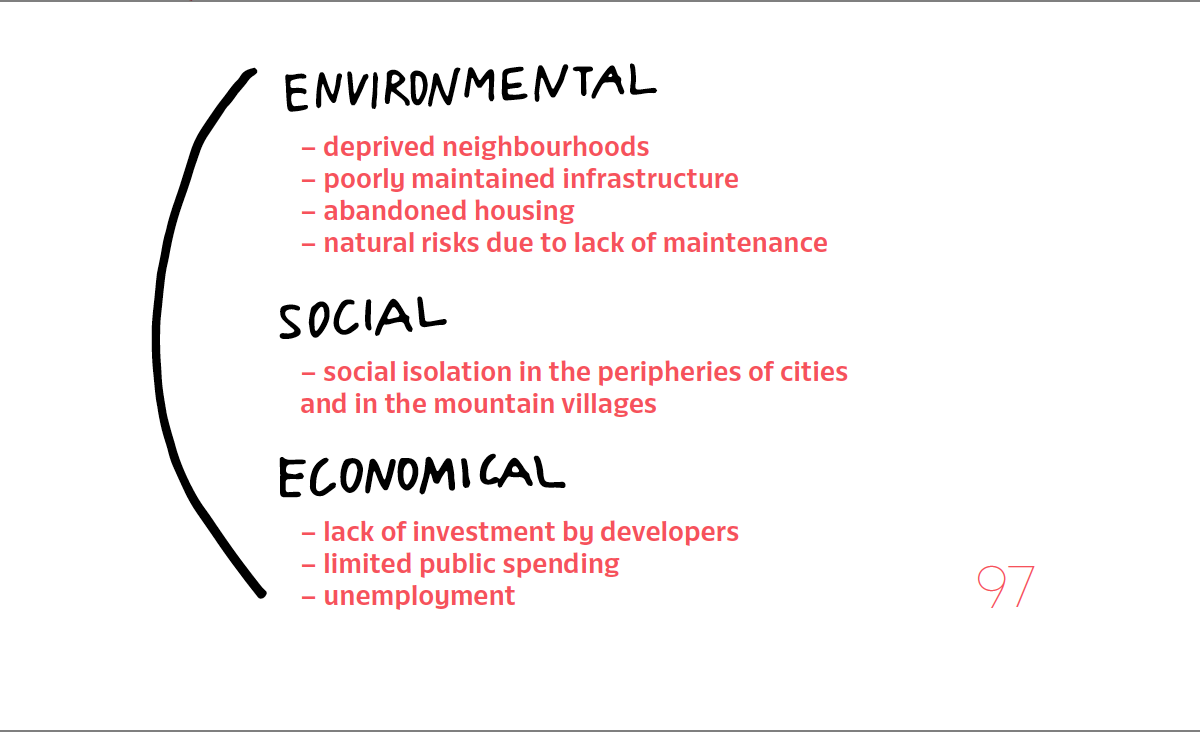

The consequences of shrinkage in a nutshell:

Local planners have tried often enough to reverse the process of shrinkage, occasionally aided by national and European funding. However, most of their efforts have gone to waste because regaining growth simply isn’t an option any more. Many decision-makers in the region are still far from accepting this fact. As an interviewee from the regional government told me, “people are just not ready to accept that a new direction is needed.”

This has deeply affected the overall approach towards planning. The large number of failed plans has created an attitude of pessimism among the regional population and among decision-makers. According to one interviewee “people have had enough of beautiful plans that accomplish nothing.” Few plans or initiatives find their way to implementation. The regional government has failed to update its regional strategy since 1991.

It is not easy to identify the changes needed to improve the situation of regions like Asturias. However, the fact that change is needed is undisputed. Most crucial is the change of perspective. As has become clear from the sheer number of shrinking regions throughout Europe, regaining growth is an unlikely scenario. Instead, what is needed is a mindset change. The scarce resources of regions like Asturias should not be invested in regaining growth, but in improving the quality of life for the remaining population.

As Hollander et al. (2009) put it “the lack of strong market demand and an abundance of vacant land create unprecedented opportunities to improve green networks and natural systems in shrinking cities.”

There are encouraging examples in practice today that illustrate a different approach to the shrinking city. The initiatives of ‘Parkstad Limburg’ and ‘IBA Thueringen’ are two good examples of former industrial regions that have found a new way forward. Both of these projects are backed by regional and national governments, but they have moved away from traditional planning practices. They focus on two things: the reuse of vacant space and the empowerment of local communities. Many of these initiatives aim to provide livelihoods for young people and social connection for the elderly.

They have also made regional funding available for small scale programmes such as urban gardening and reuse of former factory spaces. By displaying these programmes on a regional scale they attempt to inspire communities throughout the region to take ownership of their environment. Such initiatives will not reverse the process of shrinkage, but they do demonstrate that there is a potential future beyond shrinkage.

ABANDONED HOME IN MIERES. Source: author's

personal archive

ABANDONED HOME IN MIERES. Source: author's

personal archive

ABANDONED FACTORY GROUNDS IN THE HEART OF

LANGREO. Source: author's

personal archive

ABANDONED FACTORY GROUNDS IN THE HEART OF

LANGREO. Source: author's

personal archive

VACANT LAND IN THE CENTRE OF AVILÉS. Source: author's

personal archive

VACANT LAND IN THE CENTRE OF AVILÉS. Source: author's

personal archive

The case of Asturias demonstrates an extremely difficult situation that has no straightforward answer. A new perspective is needed. One can draw hope from some of the examples from abroad, yet it is unclear how widely adaptable these examples are, nor how much impact they could have. However, we can be sure that cases such as Asturias will not go away soon. If we value the inclusiveness of our future society, we’d better give them our attention.