Keep up with our latest news and projects!

It is on the urgent issue of gentrification that the placemaking movement faces perhaps its greatest challenge – and, in the end, may prove its greatest value. This will require a rigorous confrontation with the dynamics of gentrification, and a joined-up, evidence-based response. We will have to ask ourselves honestly, is placemaking part of the problem, or part of the solution? And if the latter, how exactly?

We begin by acknowledging one fact. It’s common to hear placemakers blamed for making neighbourhoods more attractive to wealthier buyers, and thereby fueling gentrification. But of course, that is an absurdly superficial view – as if keeping a neighbourhood ugly is the key to its affordability. In fact, there are much deeper forces at work with gentrification, as Peter Moskowitz documents in his book ‘How to Kill a City’. Gentrification happens, he says, “not because of the wishes of a million gentrifiers, but because of the wishes of just a few hundred public intellectuals, politicians, planners, and heads of corporations.” More particularly, he says, “gentrification is a system that puts the needs of capital (both in terms of city budget, and in terms of real estate profits) above the needs of people.”

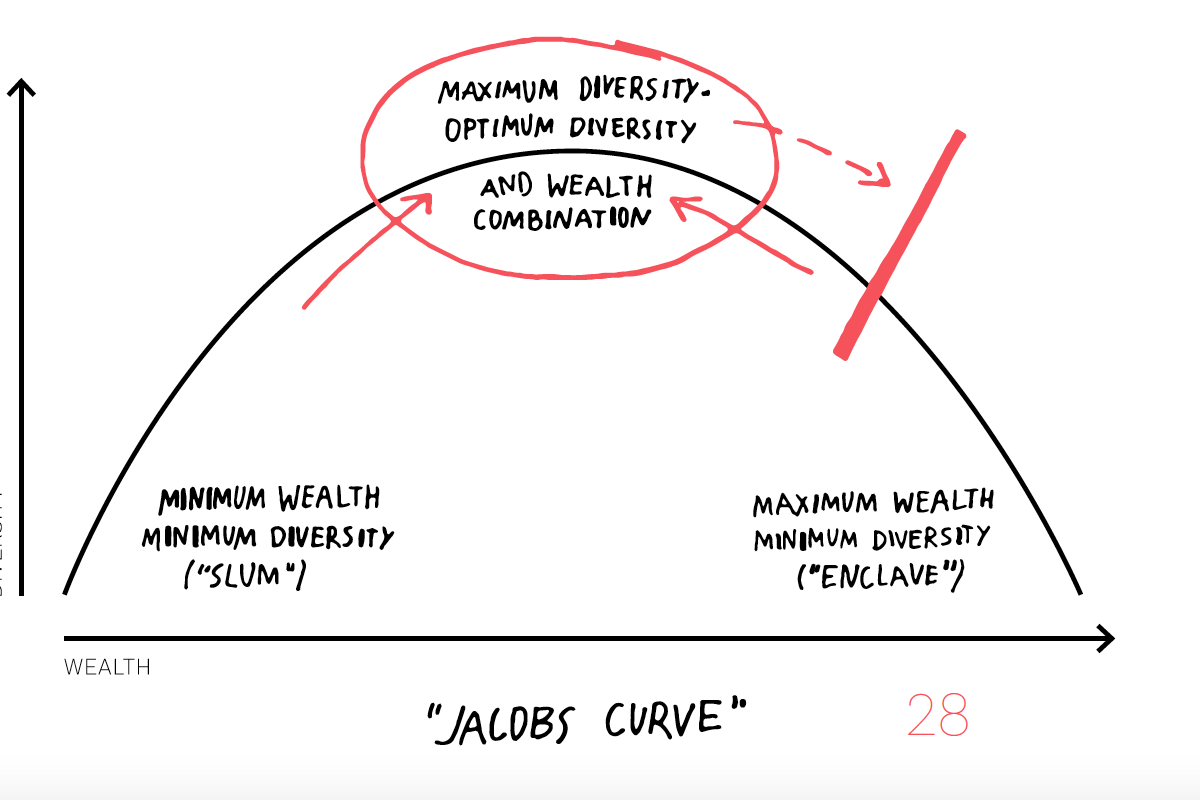

It’s also important at the outset to clarify what we mean by gentrification – and by kinds of gentrification, and what is (or perhaps isn’t) bad about them. Jane Jacobs famously argued that an increase in people with money in a neighbourhood is not automatically a bad thing, IF it thereby increases diversity and opportunities for all, and IF it doesn’t result in displacement of existing residents. So, for example, a neighbourhood that is in decline, with many vacant buildings, can be considerably helped if new people move in with higher incomes – AND if those who already live and work there are not displaced.

The problem, she said, is when a neighbourhood becomes a monoculture, either of wealth or of poverty – when it experiences what she called “the self-destruction of diversity.” That is a very bad thing – both because it displaces people who can no longer afford to live there, and because it destroys the very urban vitality that drew people there in the first place.

So we can conclude that gentrification is a very bad thing when it causes the loss of diversity and opportunity, and the involuntary displacement of existing residents – on either side of the income spectrum. In the middle range, however, is a kind of ‘Goldilocks zone’ – not too rich, not too poor, but just right in terms of its diversity of incomes (and people too).

We might think of this as the ‘Jacobs Curve’, and the goal of a city’s leadership ought to be to maintain this dynamic balance between too rich and too poor. We should focus less on whether a neighbourhood is becoming wealthier in any relative sense, and more on whether it is becoming more diverse – or less so.

The ‘Jacobs Curve’ plotting wealth with diversity, shows that there is a kind of ‘Goldilocks zone’ in the middle range, where wealth is neither too low nor too high, but sufficient to support maximum diversity. Source: author’s personal archive

How do we manage this dynamic balance? One way is to recognize when a core is overheating, and use tools to dampen the growth and shift it elsewhere. Jacobs referred memorably to using ‘chess pieces’ and other strategic moves to catalyze growth in declining areas. She urged us to look at a broader kind of diversification, not only of people and wealth, but of geography too.

Unfortunately, we seem to be intent on killing our cores with kindness. Newly popular city cores are drawing more people, pushing up prices, and driving out small businesses and lower-income residents. City leaders, alarmed at the trends, try to build their way out of the problems, on the theory that more supply will better match demand, and result in lower rents and home prices. But the efforts don’t seem to work – and even seem to exacerbate the problems. Vancouver, B.C. is a conspicuous example: it is now one of the world’s most expensive cities.

That’s because cities aren’t simple machines, in which we can plug in one thing (say, a higher quantity of housing units) and automatically get out something else (say, lower housing costs). Instead, cities are ‘dynamical systems’, prone to unintended consequences and unexpected feedback effects. By building more units, we might create ‘induced demand’, meaning that more people are attracted to move to our city from other places – and housing prices don’t go down, they go up. For example, Vancouver has been an attractive place for wealthy investors and those with second, third or fourth home, often from China.

Unfortunately, we have been treating cities too much like machines, and for an obvious reason. In an industrial age, that has been a profitable approach for those at the top, and in past decades, it seemed to fuel the middle class too. More recently, we have begun to see very destructive results — creating cities of winners and losers, and large areas of urban (and rural) decline. Even government programmes meant to address the problems have seemed at times like a game of ‘whack-a-mole’ – build some social housing here, see more affordability problems pop up over there.

In the years after World War II, and especially in the United States, the largest areas of decline were often in the inner cities, leaving the ‘losers’ of the economy behind, while the ‘winners’ (often wealthier whites) fled to the suburbs. But more recently it has been the cores of large cities that have become newly prosperous, attracting the winners of the ‘knowledge economy’.

Meanwhile, the inner-tier suburban belts and the smaller industrial cities have suffered marked decline, with a predictable political backlash from the ‘white working class’. Lower-income and minority populations have been relegated to even more peripheral locations, with limited opportunities for economic (and human) development. This gap in opportunity means a gap in the lower-end ‘rungs of the ladder’ that are so essential for immigrants and others to advance. It is a gap in urban justice too — and it is not just bad for those in the peripheries, it’s bad for the city as a whole.

This more recent pattern of core gentrification and geographic inequality has also been an unintended result of conscious policies. This time we aimed to achieve not suburban expansion, but the urban benefits of knowledge-economy cities, and their capacities as creative engines of economic development.

In the USA, authors like Ed Glaeser and Richard Florida have come to prominence by promoting the undeniable economic power of city cores. Florida’s ‘creative class’ ranks alongside concepts like ‘innovation districts’ to promote a critical mass of talent and interaction. Glaeser’s ‘triumph of the city’ points to the environmental efficiencies of compact living, as well as the economic benefits.

The books ‘Triumph of the City’ by Edward Glaeser, and ‘The Rise of The Creative Class’ by Richard Florida, both have proven hugely influential in stoking the overheating of city cores – as the authors have now admitted. Source: Penguin Books (L), Basic Books (R).

These and other authors have cited Jacobs as inspiration, particularly referencing her later economic theories. In works such as ‘The Economy of Cities’ and ‘The Nature of Economies’, she did indeed champion the remarkable capacities of cities, and their synergistic ‘agglomeration benefits’, as creative engines of human development. But she also warned against a kind of ‘silver bullet’ thinking that imagines that the benefits of an innovation district or a downtown creative class will automatically trickle down to the rest of the city and the countryside. On the contrary, she pointed to the dangers of any form of concentrated ‘monoculture’ – including even the partial monoculture of an innovation district or of a creative class. More recently, Richard Florida has expressed the same sober re-assessment of his own earlier work.

Instead, Jacobs argued for a more diverse kind of city – not only diverse in population, and in kinds of activities, but diverse in geographic distribution too. Hers was a ‘polycentric’ city, with lots of affordable pockets full of old as well as new buildings, and multiple opportunities waiting to be targeted. In such a region, economic growth — and likewise the demand for housing — could be tempered and modulated to remain more even and equitable.

This is a point that Ed Glaeser and the fans of ‘innovation districts’ might not yet comprehend. Glaeser for one has been harsh in criticizing Jacobs’ defense of old buildings – for example, in Greenwich Village – which he sees as a sentimental preservation instinct that only feeds gentrification. His formula has been to demolish and build new high rises.

But Glaeser and other critics seem to miss Jacobs’ point. For Jacobs, the answer to gentrification and affordability is not an over-concentration of new (often even more expensive) housing in the same overheated cores. Rather, we need to diversify geographically as well as in other ways. If Greenwich Village is over-gentrifying, it’s probably time to re-focus on Brooklyn, and provide more jobs and opportunities for its more depressed neighbourhoods. If those start to overheat, it’s time to focus on the Bronx, or Queens. Or Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, New Orleans…

There is almost no end to the existing good urban fabric, in the US and in other countries, that is ready for some positive gentrification, the kind that increases diversity and opportunities for human development (as we also offer targeted protections against displacement for existing residents).

At the same time, it seems more important than ever to provide good urban fabric in the suburbs too, where increasing percentages of the population live (including increasing numbers of displaced poor). ‘Good urban fabric’ means walkable, mixed, transit-served, with expanding opportunities in older as well as newer buildings. It means the same type of geographic and other kinds of diversity, achieved through conscious strategic actions to dampen, incentivize, catalyze, and use a variety of tools.

It is not wise to over-concentrate on the existing cores, in the belief that this ‘voodoo urbanism’ will magically benefit all of the city’s residents. Like George H.W. Bush’s ‘voodoo economics’, this approach reveals a naïve faith in the capacity of the top of the economic pyramid (or the core of the city) to generate wealth that trickles down to all the rest. In that sense, it is ironic that so many supposedly progressive city administrations are lured by this approach.

A second, related issue is the scale of urban plots or lots. Here too we need diversity at the smaller scales, just as we need geographic diversity at the largest scales of the city. Just as old buildings tend to be more affordable, accommodating smaller businesses and startups, so too, small plots and lots tend to be more affordable for those same users. There are other strategies for providing a diversity of opportunity too.

But as the cores experience hypertrophic growth, often the pressure to build very large buildings on very large sites also becomes financially irresistible. A mix of small and large plots, established by zoning code, can help to tamp down this tendency. At the same time, other tools can manage overheating of the core, and steer growth into new locations. For example, we can use land value tax to dampen speculation in real estate — so-called ‘Georgist’ policies. As Jacobs recommended, we can also use new public projects in new locations to serve as catalytic ‘chess pieces’ to redirect growth into more benign forms.

These and many others are examples of Jacobs’ ‘toolkit’ approach – one that is badly needed today, to cope with the dynamic challenges of rapid city growth around the world.

The lesson is that we need to become wiser stewards of urban diversity, in both scale and location, so that we can counteract the effects of gentrification, especially when it is caused by overheated urban growth. There are ample lessons in the past successes of cities that offer us effective tools and strategies. By doing so, we can support a more even and equitable growth of smaller businesses, and viable employment for lower and middle classes.

Out of that creative exchange, we will continue to get unimaginable marvels of innovation, and we might also get the next new world-famous startup. But we will also get many thousands of other healthy and creative businesses, forming the backbone of great cities.