Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Even though we may argue that there are many factors that come together to define inclusiveness, age relation is a dimension that has to be considered in every public space design process (Gehl, 2018). However, when analysing most of today’s public spaces in Romania, and even though Colin Ward, Kevin Lynch and Roger Hart started raising awareness in the 70s about the importance of opening public space for teenagers (Travlou, 2003, p. 2), not enough has been done in this regard. This is where Yplan (Young Planners Initiative) jumps in. The project started in 2015 and was led by the Romanian Urban 2020 Association. Yplan focused on involving young people in the placemaking process to: (1) raise awareness on the importance of public space, (2) empower youth to be active citizens and reclaim Bucharest’s abandoned places and, last but not least, (3) establish the basis for a dedicated public policy. In the context of the project, four public spaces were rehabilitated with the help of high school students and young volunteers, practitioners and local community representatives.

The Yplan project included three phases: awareness, training and implementation.

The awareness phase consisted of multiple micro-workshops in 12 high schools with a total of over 7 000 students. The workshops aimed to provide basic information about the characteristics and importance of public space, while also collecting information about the teenagers’ needs and expectations regarding this essential component of our cities. The main tool used for this assessment was a processed (simplified) photo of an abandoned public space, over which small teams (of 3-4 members) had to draw or write proposals. The most frequent proposals were charging spots for smartphones, cycling lanes, relaxing areas, artistic decorations or installations for various sports. The students were also engaged in the discovery of abandoned public spaces in Bucharest. An online map and a mobile application were used to crowdsource the abandoned public spaces.

The training phase included a series of short planning and design workshops, where 30 high school students formed teams with university students and planning professionals. The teams had to generate proposals for 8 abandoned public spaces selected from the database built in the first phase. To this end, the project team organized 3 urban walks, 2 analysis workshops, a treasure hunt, 3 idea generation and design studios, an experience exchange meeting with Swiss partners and a negotiation with the representatives of the local administration on the preliminary results. The most successful tools used during this process were the “idea box” and the treasure hunt.

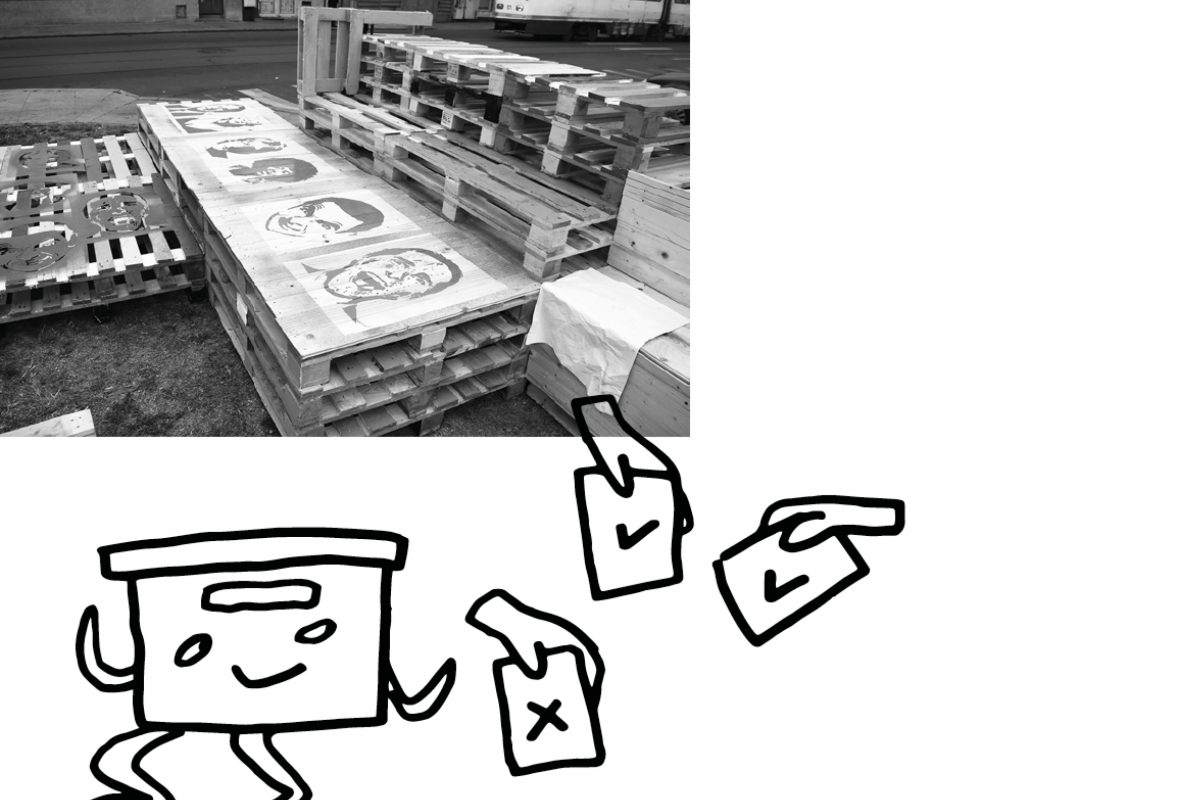

The “idea box” is a simple coloured box used to store ideas for public spaces, developed and collected during the multiple workshops. After the analysis phase was finished, the “idea box” was opened and the most suitable ideas were incorporated in the proposals.

The treasure hunt was used as an alternative teaching method. Sometimes it may be harder for teenagers to observe features that professionals discover with ease. Therefore, a list of essential features of the study areas (for instance architectural details, potential places to be recovered from traffic or parking, etc.) formed the base of the treasure hunt. Since community is essential in placemaking, the treasure hunt included multiple tasks that relied on communication with locals. In this case Candy Chang’s “I wish this was” printed on a cardboard cloud proved to be extremely useful to kickstart the dialog.

The last and most difficult part of the project was the implementation phase, during which 4 public spaces were brought to life.

This is also the phase that provided the most important lessons

Last but not least, to further continue the reconquest of public space (Espuche, 1999) and increase inclusivity, it is not enough to adapt design solutions to the needs of young people. They should be an active part of the process, as empowering them to be active citizens is essential to the well-being of our cities.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to the Yplan implementation team and especially M. Cocheci, M. Drăghia, S. Leopa and A. Lipan.