Keep up with our latest news and projects!

You can still almost see the distaste in Bertwin van Rooijen’s face. ‘The area around the station,’ says the programme manager of Via Breda, ‘looked terrible. There was a great deal of derelict land with old railway tracks and grass growing in between them. The districts to the north of the railway line, which had suffered from the odour and noise for years, were also deteriorating badly.’ We are sitting in Breda’s city hall with Van Rooijen and communications consultant Peter Jeucken. On the table is a thick book with photos and drawings of Via Breda, the programme worth about 1 billion euros that radically changed the appearance of the station area.

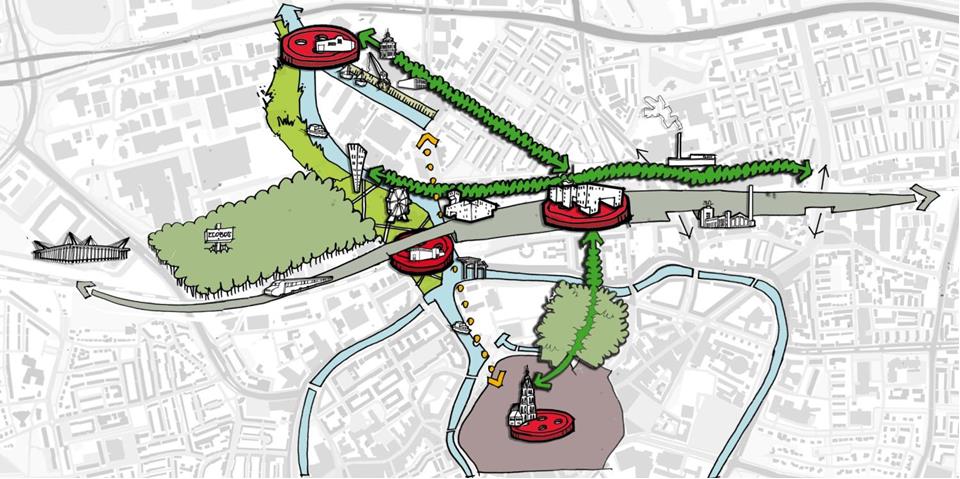

From the onset, Breda viewed the new construction of the station as an opportunity to improve the coherence of the entire city. ‘There’s an area around the station that’s as large as a city centre,’ Van Rooijen says. ‘It’s essentially a second city. It was separated from the rest of the city by the railway line. We thought it was an excellent public space, which needed to be joined to the city. The station functioned as the driving force in the plans. That’s why we deliberately gave it two faces.’

One driving force is not enough for such a large area. The municipality therefore designated a number of ‘nodes’ that would help to improve the area. One of them was the old canning factory. The municipality bought it and only allowed tenants to move in who were somehow associated with the cultural sector. It also determined that whoever performed community tasks, such as keeping the area clean, would pay less rent.

Functions for which there was no space in the old centre were designated to this area. There are many creative companies there now, for example, including a recording studio made out of straw and a small brewery. There’s a skate park, Pier15 and an urban beach, Belcrum Beach, which is run entirely by volunteers. Everything takes place based on entrepreneurship or voluntarism: subsidies do not come into play here.

The area is far from being finished. Indeed, the municipality wants to build a water storage area on the grounds where the sugar factory once stood, because a great deal of water flows this way, from Belgium for example. Housing construction has not ended yet in the Havenkwartier either. Amvest intends to build another 300 apartments where three factories still stand.

It was quite exceptional that the municipality freed the Havenkwartier from the constraints of regulation. This entailed that residents and users, like good neighbours, could determine the rules of the game, as long as they were mindful of safety in the area. That was new for the users as well. ‘”How many decibels can we produce?” they would ask me,’ recalls Van Rooijen. ‘To which I would reply: “that’s up to you. As long as you don’t get into an argument with your neighbours.” Then they immediately went and sounded out their neighbours.’

Many civil servants had to get used to the idea that the municipality was acting more as a process supervisor than a regulator. ‘When we announced that we were going to free the area from the constraints of regulation,’ Van Rooijen says, ‘we received letters from public servants telling us that we were going to fail miserably!’ ‘But now,’ Jeucken says, ‘it has had a knock-on effect. People are realising that something can also be successful if you abandon the traditional approach of ticking off the boxes and relinquish control.’

Aerial view, Station Breda - © Via Breda

Aerial view, Station Breda - © Via Breda

Via Breda has a complex mix of ingredients: a large area, a long-term initiative and many parties involved, such as the State, NS, ProRail and commercial developers. Nonetheless, the process unfolded more quickly than anticipated, says Van Rooijen. ‘The fact that many functions were accommodated under one roof in the station, in which all parties were involved, was a unifying factor. Also, things tended to accelerate as soon as something tangible materialised. That happened during the economic crisis, of all times.’

The spatial results are impressive. Take the Havenkwartier, for example, which used to be a no-go area that you wouldn’t be caught in after sundown. Now it’s hip and vibrant. ‘Recently I was at the Drie Hoefijzers, the former brewery,’ Jeucken says. ‘All of the outdoor cafés were packed. And last year there was an event about steam trains, organised by the inhabitants of Belcrum, which attracted thousands of people.’

(Device Independent Bitmap) - © Gemeente Breda

(Device Independent Bitmap) - © Gemeente Breda

The districts to the north of the centre, Belcrum and Spoorbuurt, have also benefitted. Substantial investments were made in these districts’ public space. This happened in a way that suits Breda, according to Van Rooijen and Jeucken. ‘That means: restrained but using high-quality materials,’ Van Rooijen says. ‘We deployed sleek street profiles and stuck to the historical street layout, including thirty-metre-wide avenues lined by trees. We didn’t want it to resemble an amusement park, with something different every few metres. That’s a culture we have adhered to for at least thirty years here when designing public space.’

The area in the immediate vicinity of the station is attracting many private investors. The prices per square metre here are the highest in the city and have reached the level of cities such as Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht. Is that a good thing? Yes, both Van Rooijen and Jeucken nod their head in agreement. They point out that American companies are already establishing their headquarters here, which is bound to have a positive effect on employment.

Belcrum, which not long ago was a district in decline, is now one of the most dynamic districts in the Netherlands in terms of homes sold. Referring to Belcrum Beach, real estate agents are using terms such as ‘living by a beach’ in their advertisements.

There’s plenty of economic and cultural activity in other words. But the most important impact that Via Breda has had is perhaps a psychological one, according to the two men. ‘Breda has regained its pride,’ Jeucken says. ‘Even city residents who don’t see the station’s appeal say: it has made special things happen.’ ‘From an exuberant provincial town that people left to move to Amsterdam and Rotterdam, we are becoming a pulsating city that serves a larger region and which is unifying people again,’ Van Rooijen says.

Station Breda City side - © Rene de Wit

Station Breda City side - © Rene de Wit

Belcrum on the Speelhuislaan - © Gemeente Breda

Belcrum on the Speelhuislaan - © Gemeente Breda

But both men warn against becoming complacent. ‘We must continue to focus on added value,’ Van Rooijen says. ‘If you don’t, there’s the danger that it will become a dormitory suburb. You have to ensure that you always have a viable driving force. And you have to keep stimulating and challenging entrepreneurs. For example, let them contribute to the refurbishment of buildings too. Our task is to have a strict selection procedure. If a candidate says “I don’t need to do it for the money,” then he’s out. That kind of attitude is always lethal in a project like this.’

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover moreThe Via Breda programme has transformed Breda’s station from a regional hub into a highquality public transport terminal on the High Speed Line. This has made Breda a pivotal point between Antwerp/Brussels and Rotterdam/Amsterdam. The programme concerned a New Key Project: the State provided additional funds for good urban integration. This year the station was declared the most beautiful building in the Netherlands. Apartments were built in the station area, a courthouse is being developed, and an international hotel and business centre will be located here in the future. The districts in the station’s vicinity have been addressed as well. Developments are still in full swing, particularly in the Havenkwartier. This area, about 10 hectares in size, used to accommodate large companies, such as a sugar factory and an iron foundry. Now space is being offered here for start-ups, the creative industry, recreation and residential housing. It was quite exceptional that users could go about their business free from the constraints of regulations, but also without subsidies.