Keep up with our latest news and projects!

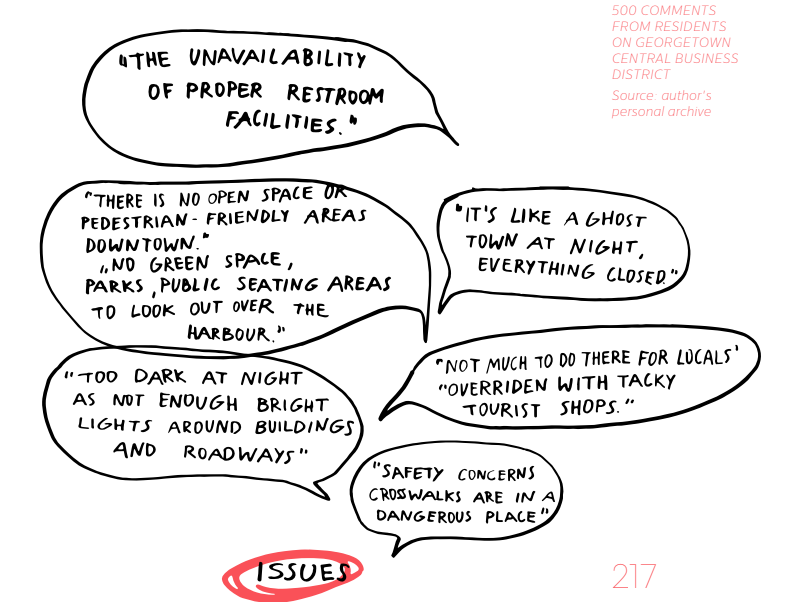

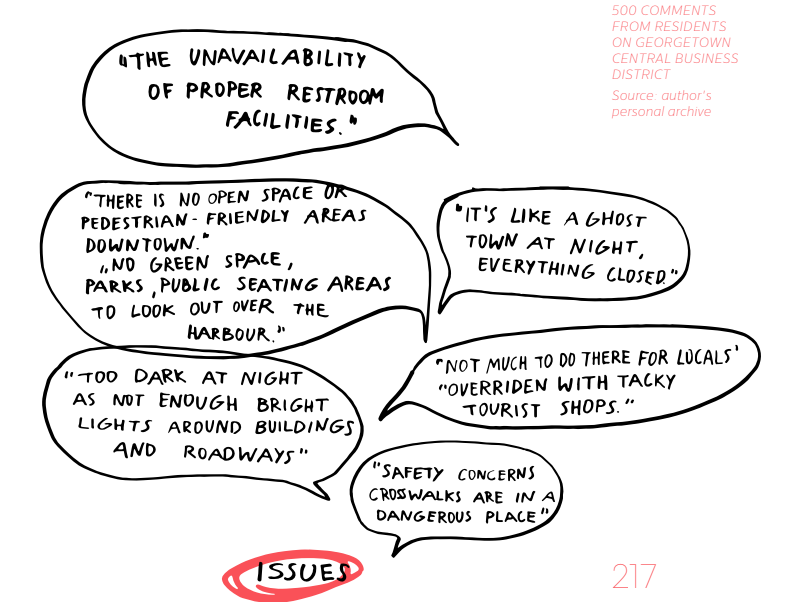

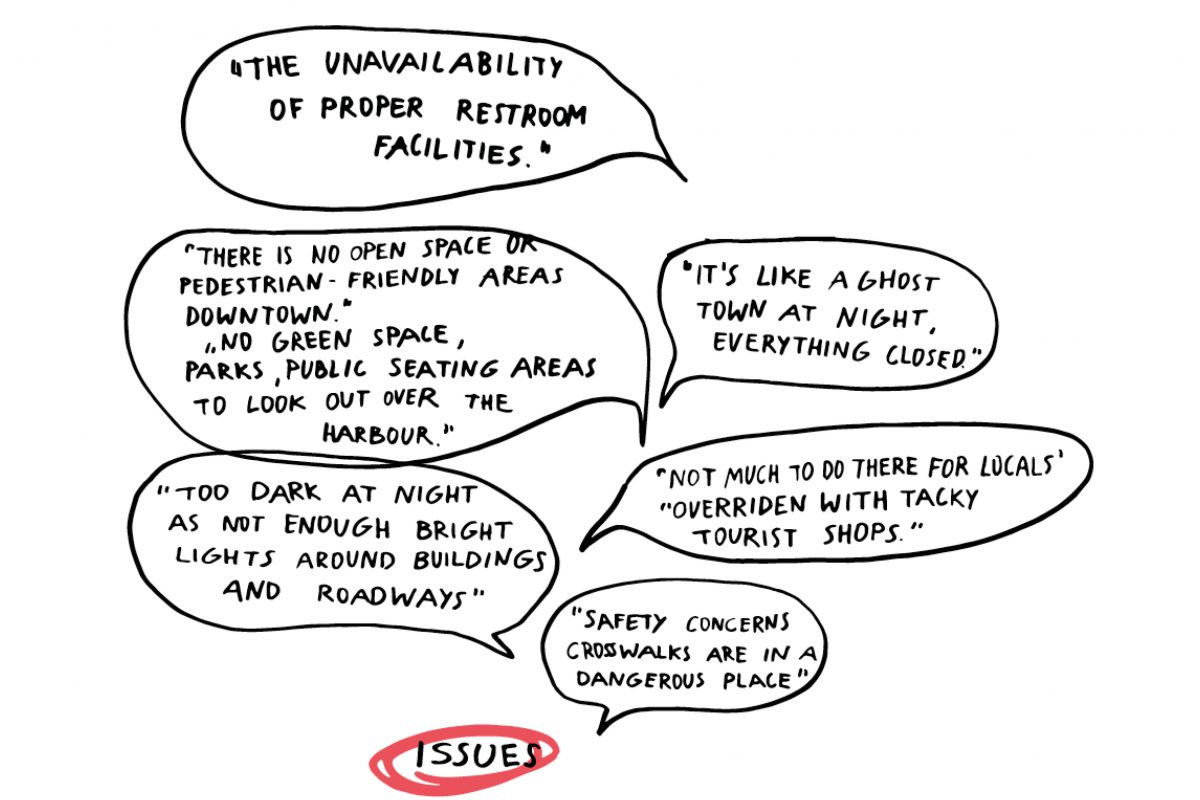

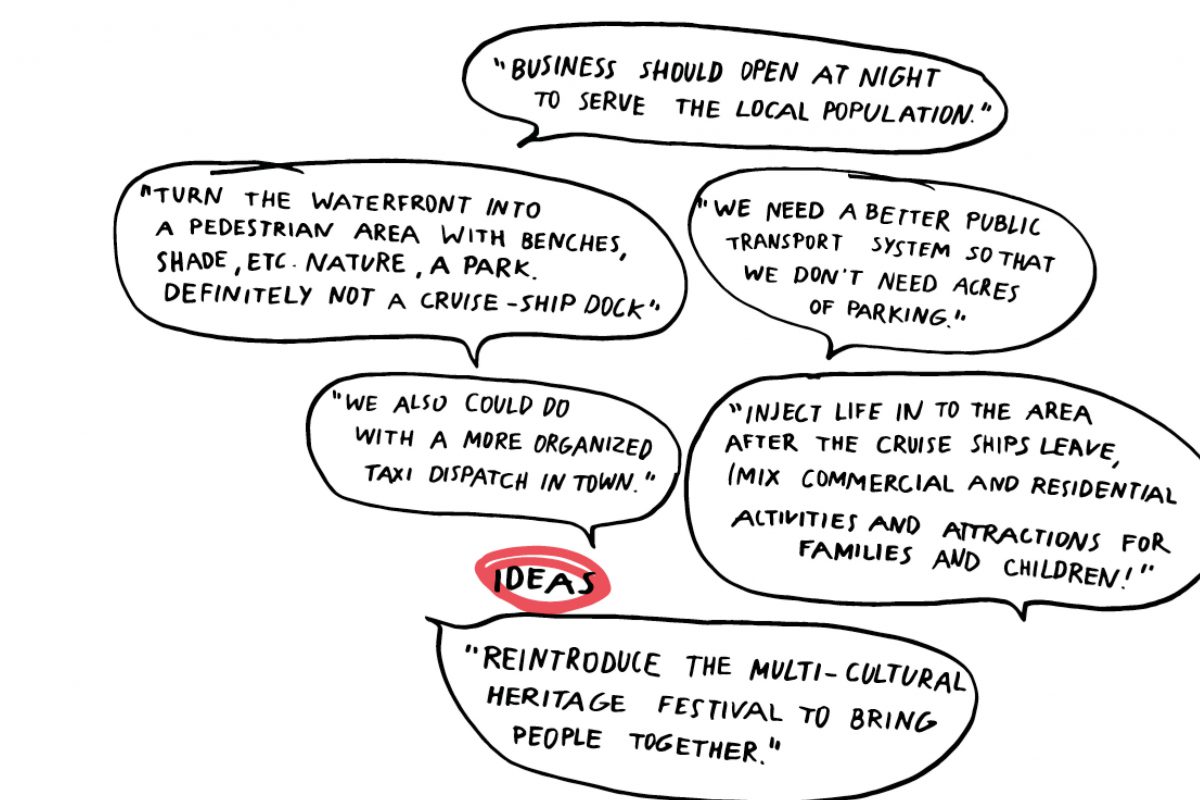

If we value community members as experts, as key witnesses to the rise and decline of the place they call home and ask them what went wrong, someone will tell you. If you ask, someone will tell you how to fix what’s been broken or lost. Often their ideas are better, more salient, comprehensive and viable than some of the ideas being imposed upon them.

First, ‘do no harm’ is not a principle espoused by the decision-makers shaping the built environment and it should be. The form of the built environment and its location are key determinants of the longevity, health and well-being of residents. Government officials, planning authorities, developers, planners, urban designers, architects, engineers, surveyors, contractors and other built environment professionals are as culpable as doctors and medical professionals in safeguarding the health and well-being of the populations they serve.

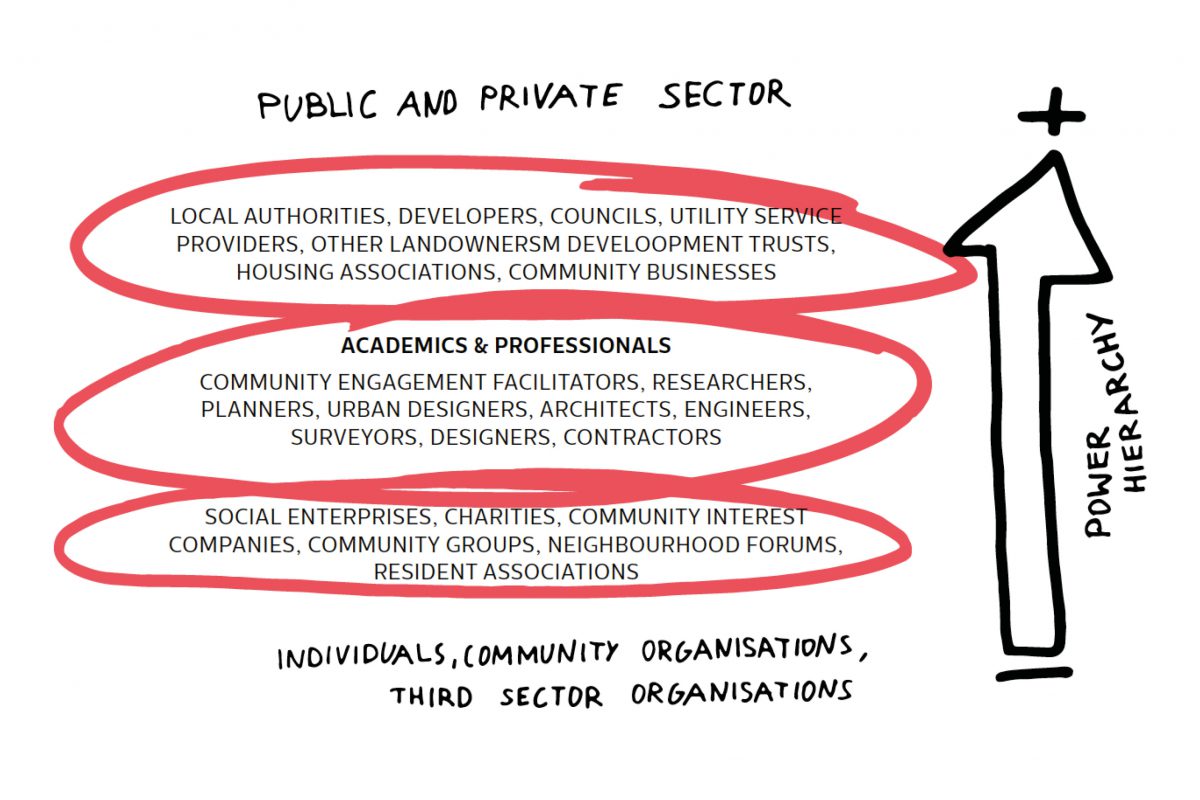

A government eager to attract investment to an area and subject it to political forces, will enact a planning policy that benefits some but not others. A developer looking to build the best and highest use and give investors the maximum return on their investment, is only interested in the buyer that can afford the product for sale. Both approaches are short-sighted, and invariably do not lead to vital, healthy places for all. However, these two stakeholders have the most power.

Communities have the most to lose when things go wrong and have the least power to influence and shape the places where they live, work and call home.

Communities can lobby their elected representatives for change or act to provide services and resources for themselves. This takes organisation and resources. Grassroots community organisations often lack the skills and means to truly engage with politicians, government agencies and developers which is why socially-conscious design professionals, academics and skilled community members are needed to engage with the community, the government and the developers, to bridge the gap and broker win-win, mutually beneficial scenarios.

In a scenario where there is a community-led or community co-designed master plan for development, the local authority can be a good steward and make decisions that support the global vision of inclusive, sustainable, healthy places and Cities for All. Developers can play a role in realising that vision within a framework. This way development is not left to chance and market forces, but deliberately focused to ensure complete neighbourhoods, compact mixed use, mixed-income and walkable developments, based on good urban design, inclusive and universal design principles.

We need to convince planning authorities and developers that rushing the community engagement process or treating community consultation as a check box exercise, benefits no one. Taking the time to engage can lead to mutually beneficial suggestions that are actionable and profitable. Starving people of information or revealing a small portion of the impacts, amplifies fear and resistance. People can mobilise to oppose a project or proposal, costing a developer time and money, and requiring planning appeals.

Even if the developer ‘wins’ at the community’s expense, people vote with their feet and can boycott a development; they can refuse to patronise it, they can speak ill of it to visitors and impact the overall footfall. If a developer is aware of the social capital i.e. the reputation it has as a development company, he or she would know it is easier to do business if the company has a reputation for quality, honesty, integrity, social consciousness and reinvesting in the communities where their projects are located. Developers who try to ensure everyone benefits from their presence will likely be welcomed by the next community they wish to do a project in because their reputation would have preceded them. Long-term building of reputation is simply good business sense.

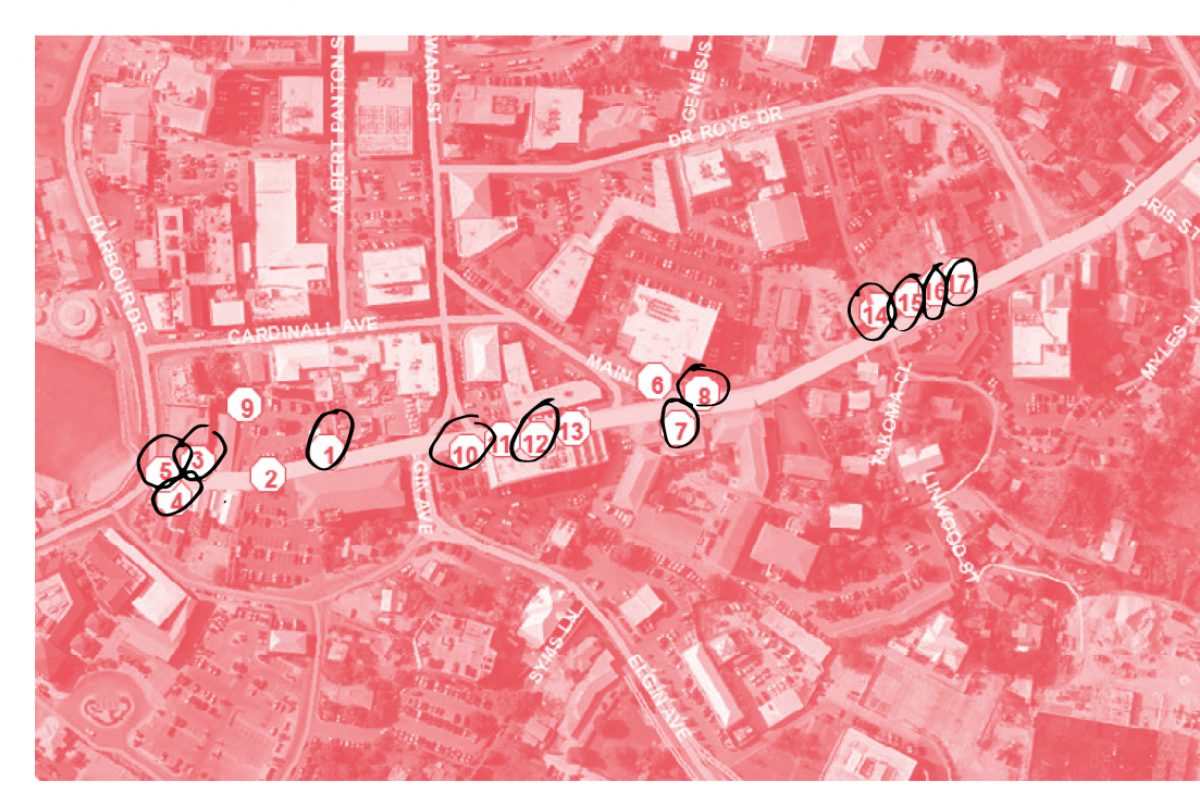

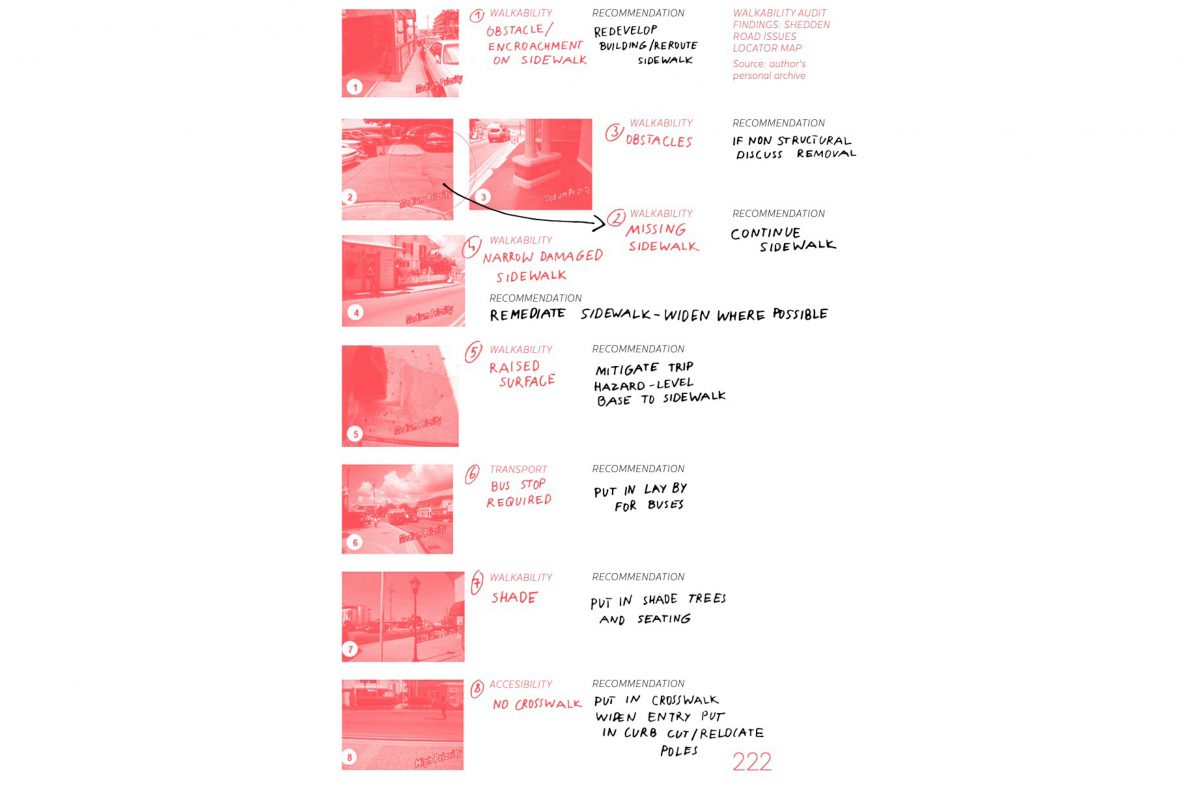

We need to give developers options for community engagement apart from town hall meeting (public hearings) which can quickly devolve into a shouting match. Other options for engagement include: focus groups, design workshops and seminars, consultations with key demographics, round tables, discussion, as part of conducting a survey or census studies, consultations using electronic media, awareness campaigns and outreach, particularly to marginalised and vulnerable segments of society. Non-traditional methods like walking audits, engagement through art or games can also be employed. We also need to encourage engagement earlier in the development process before a master plan is drawn and finalised.

Communities need to know that we have the power and authority to implement the changes and recommendations they are suggesting, or at least have access to and influence the person or people who do, so that real action, change and improvement will result. People need to see progress and be kept informed. We have to understand that communities with a history of having decisions imposed upon them without their consent are hurt, angry, damaged and frustrated. It will take time to heal that broken relationship and rebuild trust.

Stakeholders can try and meet people where they are and accept them as they are; see their humanity and empathise. What would you want if you lived there? What would you need? How would you feel if you had no control over decisions affecting your life? What would you do if roles were reversed and you were part of this community? How would you want to be approached and treated? Probably with respect as if you had value, as a person, a human being, not an inconvenience, annoyance or a stumbling block to be removed. Speak to community leaders, win their trust and these key influencers will grow your circle of influence within the community. Communicate, deliver and honour your word. Try to work around a problem, identify the end goal and provide options.

Where the relationships between the Council, the developer and the community are too damaged, it may be helpful and necessary to employ a neutral intermediary to provide honest feedback to all parties and make recommendations that result in win-win scenarios. Politicians, senior management and executives need to be prepared to act on recommendations, to show commitment to the community, rebuild bridges of trust and foster positive relationships. Sometimes it is important to accept that the damage done is irreparable. In those instances, Councils need to be able to move on from the current developer and engage a new one whose ethos is more in line with the aspirations of the community. If the latter is wary of anyone new coming in, the Council has a duty of care to work with community leaders and empower them, by providing land, built assets and access to resources, skills and services. The community may want and need to heal itself from its own Housing Association or Trust by running and managing its own Community Hubs and public gathering places.

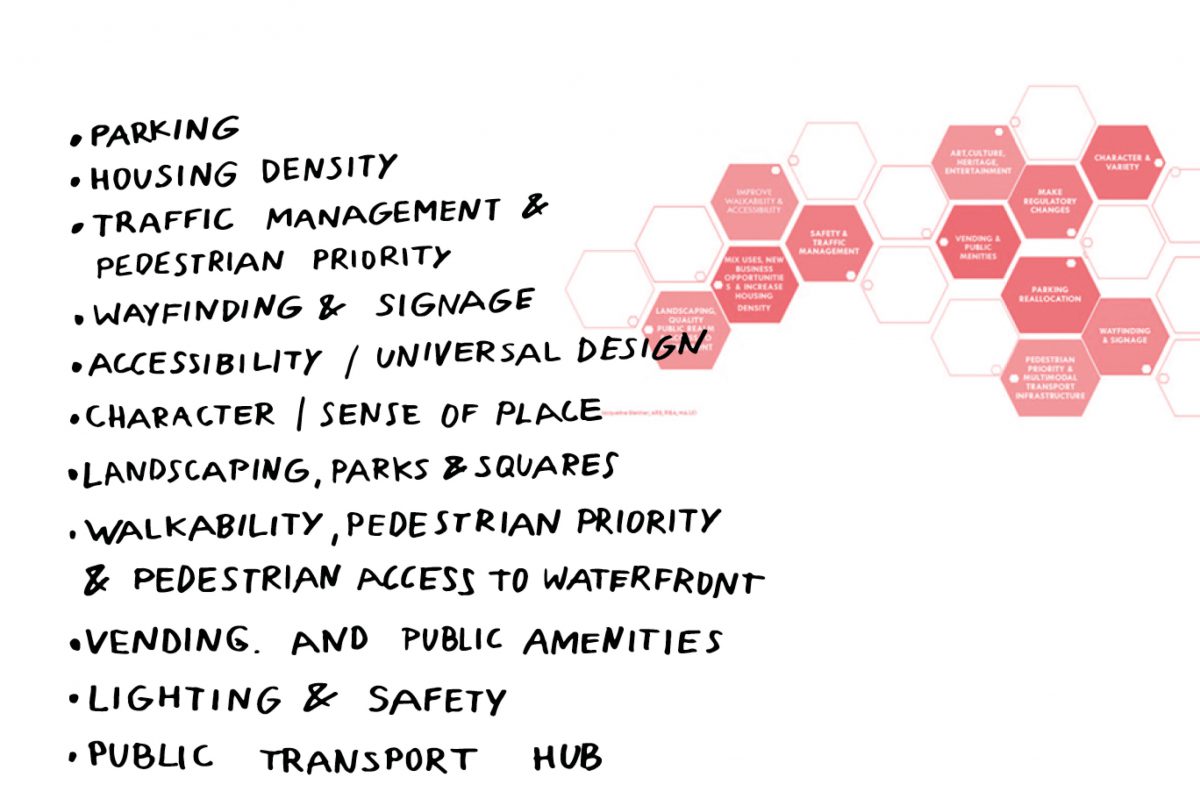

Group community input into themes. Rank strategies and recommendations into high, low and medium priority as well as long-term, short-term and intermediate. Determine values and timeframes for these priorities. Try to realise high priority quick wins, to build momentum and cement trust. If the time and investment required are too high in the short-term, the community may wish to build capacity or address another high or medium priority project they can execute with the resources available.

To foster community engagement and buy-in, identify any recommendations that can be actioned by the community and organise people to be able to implement their own recommendation(s). This will empower them to help themselves by helping others. Simple actions that lead to tangible outputs can change mindsets, freeing people from victimhood and transforming them into leaders who can implement meaningful change in their own lives. This sense of accomplishment and empowerment can spill over into other areas of community life, and inspire other community-led projects that benefit everyone.

At the heart of it, Councils, developers and businesses are guided by self interest. They safeguard whatever resources they have control over and seek-cost saving recommendations as opposed to value-adding recommendations. To leverage political and business support, community organisations or their representatives need to understand the factors that motivate these potential partners and identify target stakeholder groups who would be willing to invest in the community because of alignment with their political mandate, Community Investment Strategy (CIS) or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

Other considerations in pitching to a stakeholder include identifying key potential programme or project areas in which the stakeholder can invest. Communities and stakeholders will need to define roles and responsibilities, bearing in mind that stakeholder will likely set the budget, scope and timeline. It is important for the community to discuss with the stakeholder the exit strategy and handover, so the community has time to build capacity in preparation for the handover and get ready for the implementation and execution of any self-financing initiatives. It is also important that both parties monitor and communicate project results and advertise or promote successful projects to attract further community investment in addition to building stakeholder reputation and social license to operate.

A means of attracting investment and raising awareness is media coverage of community execution of smaller, quicker, cheaper projects. Those can be leveraged to attract investment for larger projects from community businesses and other investors. There needs to be some level of community self-organisation that can identify and communicate common or shared needs, come up with strategies and embark on a course of action to implement them through partnerships, collaboration and fundraising. It would be prudent for a community to embark on a multipronged strategy to generate investment, for short, medium and long-term projects and initiatives.

Communities need to be aware of their legal rights to be able to effect whatever change is within their remit. To do this more effectively, they need to know the status of their assets. These assets, if properly developed and managed, and if made accessible and inclusive, can potentially improve health, well-being, economic productivity, spending power, and social cohesion.

Ways of doing this include:

Where communities come together to support those in danger of displacement or disenfranchisement and mobilise to lobby for, to create or retain public spaces, housing and jobs for and within the community area, they can bring about change and preserve more of community and social networks. Policies like rent control can allow community members to remain in place, with affordable long-term leases.

In closing, all parties involved in the community and in the development of the built environment should do some post-project evaluation and a ‘lessons learned’ exercise to discuss and debrief what worked and what was ineffective in the context of that place and its community. Key universal takeaways should be recorded by intermediaries to inform a toolkit or toolbox of strategies and techniques that can be applied in another context, making adjustments to consider for unique characteristics like climate, place, people and culture.