Keep up with our latest news and projects!

‘Life in Maastricht largely takes place outdoors. This is particularly evident in the traditional celebration of carnival,’ says Jake Wiersma, urban planner at the municipality of Maastricht where one of his main concerns is the quality of public space.

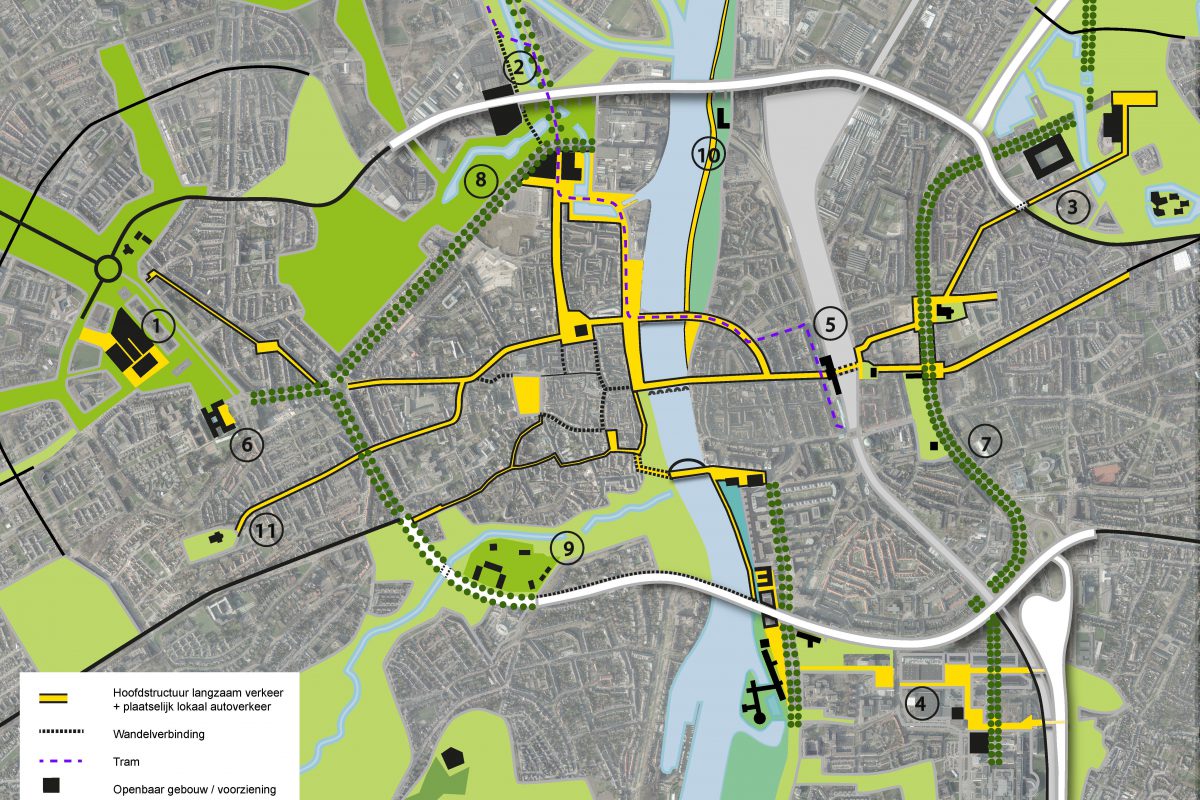

Placemaking is a new term for something that has occupied a central position in Maastricht’s urban development policy for years. Traffic structure is a crucial element because in placemaking everything revolves around places and flows. There are now great opportunities for putting this policy into practice, since Maastricht’s infrastructure is undergoing a thorough revision. Around the year 2000, the motorway running along the Maas River was tunnelled to make room for a boulevard, in order to revive the relationship between city and river. The A2 motorway was recently tunnelled as well, which freed up a sizeable strip of land above ground. By moving the Noorderbrug trajectory slightly northwards, the inner city is once again connected to its surroundings. This has also created a substantial low-traffic area, which is an important precondition in placemaking.

All of this dovetails with Maastricht’s plan to create better public spaces. Maastricht is the second-most visited city in the Netherlands, after Amsterdam, and just like the capital the municipality of Maastricht wants to prevent its historical centre from becoming totally congested. New forms of placemaking, also extending beyond today’s city centre, will have to help achieve this objective.

Slow traffic in urban area

Slow traffic in urban area

Placemaking requires more than just the banning of cars. You also have to take slow traffic flows into consideration, according to Wiersma, which are essential for creating favourable conditions for hospitality outlets and amenities. These are a prerequisite for developing lively and attractive public spaces.

With respect to the latter, extensive experience has been gained with Plein 1992 in the new city district Céramique to the east of the Maas River. Here, the new library/ city hall constitutes an important source of vibrant life. A new footbridge across the Maas River facilitates the flow of pedestrian traffic, which is positive for the hospitality industry, but not always appreciated by local residents.

The most drastic and eye-catching project has been the tunnelling of the A2 motorway, whose construction started in 2000. The recent opening of the King Willem-Alexander Tunnel freed up a substantial strip of public space that will be put to excellent use in the coming decades. ‘That’s quite a challenge,’ admits Wiersma.

A ‘Green Carpet’ has been planned: a broad, tree-lined avenue surrounded by buildings, with a lot of green and a generous path for cyclists and pedestrians. The buildings will consist of stately homes to create a residential lane with allure. The area will have limited traffic rather than being traffic free. That’s not really necessary. With a density of 15,000 motor vehicles a day, it’s essential to install pedestrian signs, traffic lights and zebra crossings, but if the numbers are lower it should be possible to cross safely without these devices. By keeping traffic intensity beneath this ‘tipping point’ the municipality wants to create an entirely different perception and use of the street. All these points will be laid down in a design vision statement prepared by the developer and the municipal council.

The area between the back of the railway station and the current shopping centre on the A2 motorway will have a more mixed and vibrant character. The choice to locate the central facilities here was deliberate. A walkway has been proposed, to be built either above or beneath the railway tracks, which would improve the connection with the inner city. This, too, will create the necessary precondition for placemaking.

By moving the Noorderbrug trajectory, Maastricht will gain more public space to the north of the centre. The old fortification area will be linked more directly with the inner city and space will be created for a park that could serve as a venue for events.

All of these projects will provide more room for new municipal facilities outside the historical city centre. For instance, the public library and the Bonnefanten Museum will be relocated to the Céramique district. But you can’t go on shuffling facilities around forever, Wiersma warns. ‘Removing shops from the inner city is usually not a good idea. A city has to cherish what it already has and expand where possible.

The aim of expansion should be to create a new urbanity outside the city centre, for example by providing space for start-up entrepreneurs. ‘The southern part of the province of Limburg,’ Wiersma says, ‘has to convey an urban feeling without the need to live in the busy inner city: relaxed green living with the inner city just around the corner. The districts around the inner city in particular have to offer better connections to the historical centre.’

A new aspect is that residents and entrepreneurs have to receive more leeway to develop their own initiatives and gain ownership of public space. One condition, however, is that the initiatives must have the support of the entire street and not only the entrepreneur, explains Wiersma. For example, if businesses want to expand their sidewalk terraces they have to ensure that they coordinate their plans and that sufficient space remains for pedestrians. This way the street arrives collectively at a solution.

‘It’s a challenge for the municipality to safeguard the balance between public and private and to avoid putting pressure on the public quality of the city,’ concludes Wiersma. ‘We accomplish this by working more closely with entrepreneurs, residents and other parties involved, and by presenting different scenarios with different perspectives. By getting together more frequently we can work on a common goal.’

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover moreMaastricht is undergoing major infrastructural changes. The A2 motorway has been rerouted through a tunnel, for example. Since late 2016, high-speed traffic in the east of the city has been flowing through a stacked, two-tier tunnel instead of across residential areas. This intervention has freed up a strip of land 2.3 kilometres long. Moreover, the Noorderbrug trajectory, which is an east-west connection to Belgium, has been moved slightly northwards in order to give the inner city more space and ease traffic congestion. All this dovetails with Maastricht’s plans to keep cars out of the city, create better public spaces, and enhance the city’s relationship with the river and water in general. Placemaking has been playing an important role in this process.