Keep up with our latest news and projects!

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” — Jane Jacobs

Accounts of city making can sometimes read as a kings and queens’ version of history. There are the well documented contributions of Robert Moses, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Ebenezer Howard, the starchitects et al. Examples such as these continue to inspire civic leaders, philanthropists, mayors and developers to pursue their visions and grand projets. All of course have merits and achieved good outcomes. But it is hardly consistent to argue on one hand, that it takes single-mindedness and strong leadership to push things through, and on the other, that inclusivity and participation in the process are the hallmarks of good placemaking.

That good placemaking is essentially a democratic undertaking is increasingly unchallenged. Whilst this may be acknowledged in practice, it does not always flow through to result in personal and professional behaviours which exhibit the practical commitment to deal with all interests equitably.

Much of the regulation around urban planning is aimed at ensuring that no single interest can run roughshod over other views. It attempts to redress the imbalance between those with power and influence over land, and those others who are impacted by change. But striking that balance has proved elusive, and the intrinsically adversarial nature of the development process results in partisanship.

Even what appears as a level playing field of participation can be misleading, serving to mask disparities in resource, power, technical capability and influence. Some have sought to benefit from this obfuscation, peddling the notion that all that is required is an increased level of understanding, that can be achieved through better communication (comms). The dark arts of the place spinners.

All too often though it is actors’ pursuit of one-dimensional outcomes, that bedevil placemaking success; those that serve narrow, technical, social or financial goals, and ignore the broader user perspective. For example, transport prescriptions, over engineered for the needs of vehicles, architects’ visions of streets in the sky, and other technocrat follies all happen when the focus on the user’s human needs is lost.

Similarly, development economics can result in speculative and successive waves of resi-led, retail-led, or leisure-led development. These may stack up for the short-term bean counter but make no sense for the longer term at a community level. Sustainability demands a more nuanced evaluation of development needs than can be achieved by simply relying on the market value model. While societies have struggled to find a more efficient allocator of capital investment than the market, the market’s deficiencies are highlighted in the field of placemaking where a complex range of considerations needs to be ordered. It is not acceptable that poor investment decisions are simply punished by financial failure as communities are faced with the legacy of unsold property, boarded up units and barren public squares.

The evolution of the placemaking philosophy brings the user of place closer to the centre of the debate. It respects the imperatives of the different disciplines – urban design, architecture, mobility, sustainability even, dare I say, accountancy, but it understands that solutions which favour a single perspective are unlikely to deliver common benefits.

Thankfully the march of the placemakers over the last generation has won a voice for the previously under-represented, those that live and work and are the users of place. And this has initiated the development of more holistic approaches. But the battle was not about removing one set of dominant interests and replacing them with another. The aim is to harness all interests, what Jane Jacobs describes succinctly in our opening quote as everybody. This would include those who invest in an area, create employment and wealth, and run commercial, cultural and social enterprises.

What is required to successfully integrate these interests into the placemaking endeavour?

In attempting to answer this question three very different factors must be considered. The first is cultural and can be referred to as partisanship – the inability to rise above the ideological divide that separates the private and public sectors. The others are more practical and concern the mechanisms that are available, and the framework for their application. The tools and their box if you like.

First, keep an open mind towards private partners

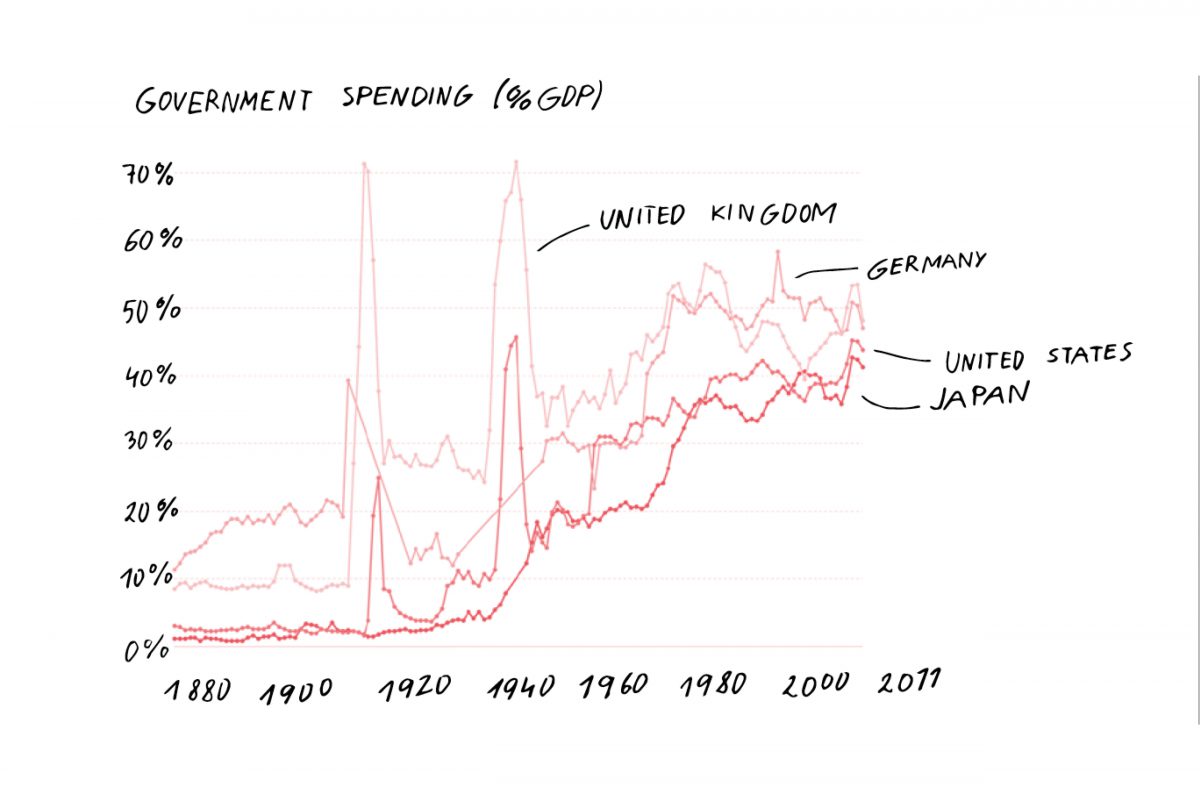

Placemakers need to be sector neutral, and impartial in their intent to foster an inclusive dialogue with private and public interests. Not least because the advent of globalisation has reversed a longstanding trend where government commanded more and more of countries’ GDP. In recent years the need for nations to compete in world markets entails a shift in the balance of resources away from the public sector and there is little evidence to suggest that the limits imposed on government spending across the globe will be lifted any time soon.

But it is not only for resources that the private sector should be embraced. It should also be tapped into for its energy, enthusiasm and expertise.

Some working in the field have found it difficult to stretch their definition of ‘everybody’ as far as to embrace the private sector. There is an ideological hesitation here, manifested as public sector good – private sector bad. This has no place in inclusive placemaking. Or perhaps it implies a lack of confidence, a fear that any hard-won concessions in advancing community interests in the placemaking arena would be threatened by relaxing the guard. Given the disproportionate balance of power this is an understandable, but ultimately self-defeating stance.

Ideology should be banished to the realm of the political. Genuine fears however should be taken seriously and approached through a series of confidence building measures, some of which are explored below.

Second, understand the business models and be aware of place spinners

Whilst placemakers need to be sector neutral, they can’t be sector blind. The tools and techniques of community engagement aren’t the most appropriate implements for engaging with the private sector, and fresh approaches are called for.

Similarly, if the best place outcomes are to be achieved, the private sector will need to continue adjusting its stance and its models. It has begun to embrace the language of placemaking (the letter but not the spirit, cynics would say). Placemakers must be the ones interpreting and enriching this language, growing the dialogue and helping convert words into deeds.

In this context it is important to distinguish between the placemakers and the place spinners. What defines the difference is that the former have a real and active interest in achieving place outcomes, and in co-creating the narrative of place, whilst the latter have narrower objectives, serve a partial interest and simply seek to convey a pre-ordained narrative as a way to secure selfish goals.

This analysis positions placemakers as brokers between competing interests, a role that demands independence in order to win the trust of different stakeholders. And as facilitators, process managers that can frame dialogue, and reach consensus.

One of the remedies to the imbalance of power during large-scale housing renewal in the UK was the appointment of so-called Tenants Friends. They provided support to residents and commercial leaseholders through the planning and development process. Crucially, independently funded, they were empowered to represent the interests of these ultimate end-users. Perhaps there is a hint here to a potential role for Place Champions, a role independent of the developers and the regulators. It is not difficult to envisage how these might operate. They could be funded through a very modest percentage of total development costs, or simply through dispensing with the costs of the place spinners.

Third, move beyond the plan towards long-term place management

Of course, placemaking is much broader than development, it is an open-ended process that needs to be continually reviewed and replenished. Reaching agreement is a necessary but insufficient stage. The next steps of recording accord and acting thereafter present different challenges. Stipulating a set of agreed placemaking objectives is one thing, difficult in itself but achievable, as has been regularly evidenced. However, setting those objectives out with precision and clarity, and in a manner that remains relevant and current over time is more problematic.

The current English experiment in neighbourhood planning illustrates some of the dilemmas. The process has often been productive, bringing together a range, if not the full range, of different stakeholders. But the final outputs are often underwhelming.

Neighbourhood Plans are essentially land use based. Broadening their scope into what could be referred to as Whole Place Plans could encourage wider analysis and prescription, bringing social, economic and cultural considerations into play. Getting the private and public sector to jointly work on the production of Whole Place Plans and commit to their implementation would be a means of formalising co-operation. To date there has been too little exploration of how this might work in practice.

For the private sector to engage meaningfully with the placemaking agenda will take time and effort and this will require new frameworks if it is to be sustained. The private sector can see the merits of mutual action beyond the narrow pursuit of profit. Enlightened self interest it may be, but the collateral impact can be wholly positive. There is often the ‘will’ but not always the ‘way’. What is lacking is the superstructure to support joint action. History has thrown up numerous formulations such as the trade guilds, chambers of commerce, professional associations and the like. What should the equivalent of these look like in the digital era.

Around much of the English speaking world Business Improvement Districts (BID) provide part of the answer, and a growing body of successful placemaking outcomes. The legislative framework required to support their establishment has also been developed in Germany, Albania, the Netherlands and Sweden. Where they exist they should feature in the placemakers armoury.

Although the flexibility of the enabling legislation for BIDs is commendable, it does mean that interpretation of their role is multi-fold and placemaking performance patchy.

A full and impartial analysis of their record in engaging the private sector in placemaking is overdue. An understanding of which of their features are critical to their contribution would allow that learning to be transferred to other scenarios where they don’t yet operate. A key role for the emerging European placemaking network should be the capture and dissemination of that learning.