Keep up with our latest news and projects!

Hongdae today is one of the trendiest and most lively districts of the buzzing city of Seoul. The district is known for its thriving art scene, night clubs, galleries and student life. Bart Reuser, founder of the Dutch architecture company NEXT architects, lived in Seoul in 2012 and explored the planning dynamics behind the successful transformation of the district. He documented his findings in Seoulutions, a comprehensive guide for planning professionals and an ode to the dynamic city.

Reuser became fascinated by the district’s continuous change. Within the year he attempted to pin down a clear image of the city, only to find whatever he just got to know was changing in front of his very eyes. He lost his favourite coffee place, bakery, restaurant and his orientation, but gained a fascination for the ever-changing dynamics of the city in exchange. For Reuser, Hongdae became the representation of this continuum and proved to be an inspiration to rethink planning; especially relevant when perceived from the Dutch context, where the comprehensive urban planning system — resulting in what Reuser calls the ‘conditioned city’ — was losing momentum at the time. Hongdae’s story is one a neighbourhood that accommodates the complexity of urban transformation through an approach he coined the ‘city of flux,’ where guiding rules are put in place to balance the unprecedented opportunities and progress, emerging from economic forces at play.

Hongdae was established in the 1960s as a sparsely populated residential neighbourhood, with villas mainly for higher government officials and other well-to-do residents of Seoul. The private lots were traditionally fenced off by high walls, separating the public realm from the private domain. But over the course of 50 years, the residential neighbourhood developed into a mixed-use area, gradually turning the district inside-out. The first spark that ignited the success of Hongdae today, was the growth of Hongik University, the most established art school of Korea, which attracted artists to locate in its adjacent neighbourhoods. This has left a permanent mark on the district as the habitat of the city’s creative community.

Reuser found that the appeal of the transformation of Hongdae lies in the effective combination of the planning schemes facilitating urban development in Seoul, and the entrepreneurial mindset of its residents. The Korean urban planning system — influenced by the Anglo-Saxon tradition — is guided by three main principles: zoning, building and bonus regulations. Zoning as a planning instrument globally dictates the area’s program, and plans for residential, commercial, industrial or green spaces, without being overly restrictive. While Hongdae is facing continuous transformation, it is still primarily categorised as a residential area. Within this category however, the Korean planning system allows for mix-use, and doesn’t exclude functions per definition. There is therefore not much pushback for any residential neighbourhood to gradually develop into a commercial area with a great variety of amenities.

As a second control mechanism, the building regulations define the boundaries of a building. In Hongdae, these regulations have made way for creative interpretations, like adding extra floors on the same footprint. The flexibility of the regulations dictated for instance that an underground floor may replace a parking lot if at least one-third of the layer added was above the surface. This then resulted in underground spaces with noticeably high ceilings, that turned out to be of excellent use as clubs or artist studios.

The bonus regulations, lastly, are among the most innovative control mechanisms. The regulations are based on New York’s incentive-based planning system, and invite the owner of a building to invest in the quality of the built environment, in return for permission to add more quantity. Densification thus comes with a quality impulse. As Hongdae traditionally had narrow streets, the city’s planning authority invited building owners to demolish the high walls around the estates and open up the facades. The result is a great city at eye level and an inviting public life.

A property in Hongdae before renovations (2009)

A property in Hongdae before renovations (2009)

A property in Hongdae after renovations (2011).

A property in Hongdae after renovations (2011).

The Korean planning system moreover perceives owner-occupants as entrepreneurs who are invited to seek new opportunities with their real estate, instead of residents that need to be protected against unforeseen changes. As most residents of Hongdae have invested in their real estate for pension purposes, they continued to make investments over time to adapt their building to emerging demands. A floor was added here, a staircase was created to increase connectivity, or buildings were split between the original and ongoing residential function and a commercial amenity at street level. This gradual change has led to a great variety of materials used and a diverse and walkable district with a fine grain, and a surprise on every corner. Some may call it a mess for lack of architectural cohesiveness, but Hongdae clearly shows how such a flexible approach to area development creates multiple values, ranging from creative use to financial success and social benefits for its residents.

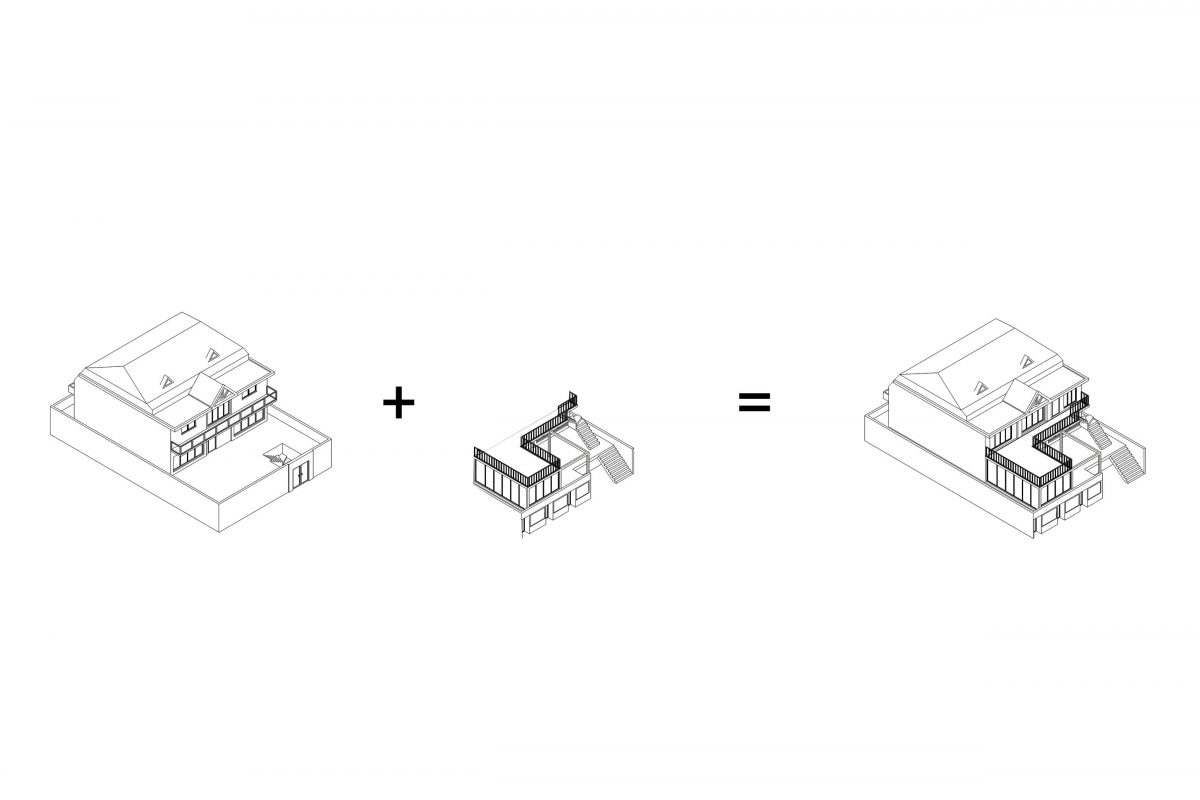

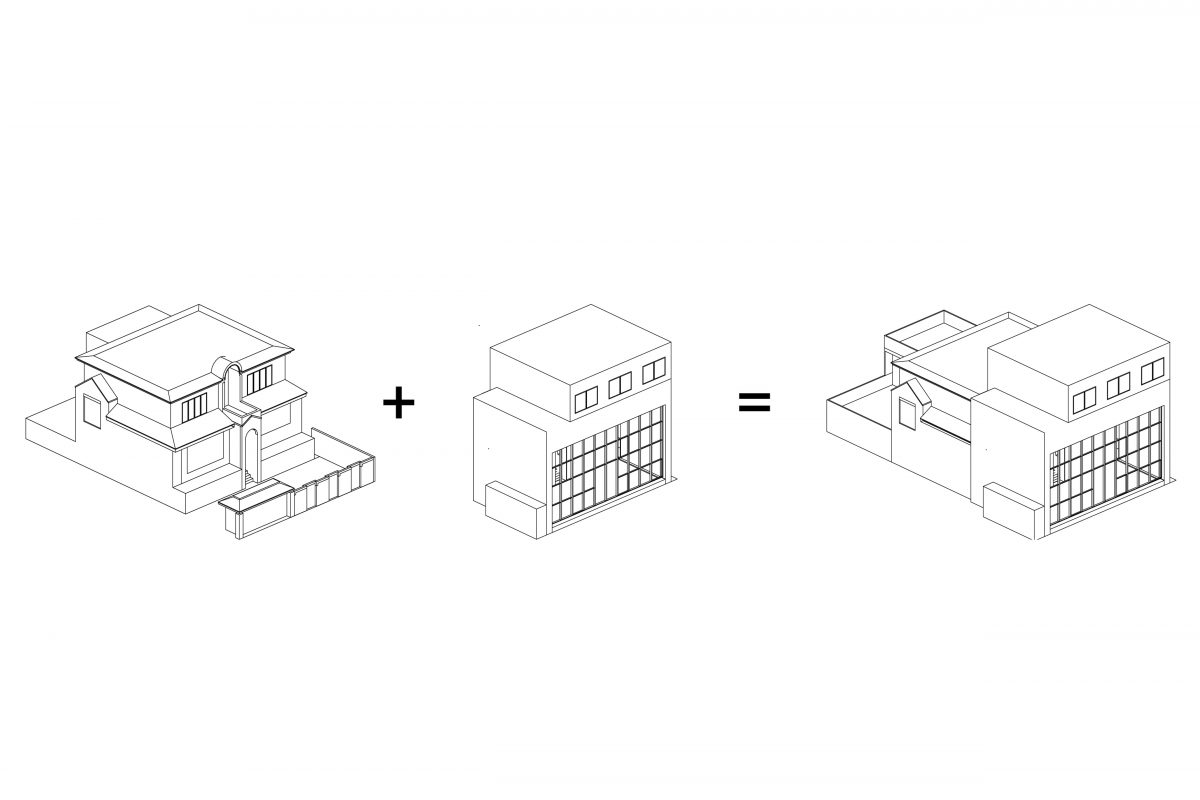

Visualisation of possible architectural changes.

Visualisation of possible architectural changes.

Visualisation of possible architectural changes.

Visualisation of possible architectural changes.

Reuser shows how the prevailing restrictive planning mechanism in European cities has a lot of upsides, but there are valuable lessons to be gained when observing how Asian cities accommodate development. Urban planning in the Netherlands, for instance, is a risk-averse system that is built around jurisdiction and protection, but it creates an unequivocal dependency on predictability and security. This may have worked for a long time, when urban development was synonymous with greenfield development. However, a more complex urban environment nowadays asks for a more dynamic set of control mechanisms. As urban development and transformation nowadays is often times set in populated urban areas, with an existing community of stakeholders, the planning system should be adaptive and flexible. Reuser pleads for a planning system that allows for spontaneity, private and civic initiative, gradual growth, alternative mechanisms and innovative business models to make our cities more resilient in continuous change.