Keep up with our latest news and projects!

One of the most authentic shopping streets of Rotterdam West, the Nieuwe Binnenweg, is under reconstruction. Over the last few decades the street suffered from economic decline and degradation. With a vacancy rate higher than other streets and a rather low variety in shops, the Nieuwe Binnenweg was in need for an upgrade.

The Binnenweg, originally a country-road between the towns of Rotterdam and Delfshaven, dates back to the 13th century. The 1860’s industrial boom of Rotterdam’s harbour area marked the beginning of development along the Binnenweg as an urban street with a total length of over two kilometres (1.5 miles). Originally, the developments were mostly dwellings. In 1900, only 57% of the premises had shops on the ground floor. By 1940 it was 87%, making the Binnenweg an urban high street with all sorts of shops, from groceries to luxury goods such as jewellery and fur.

The architecture of these 19th century developments was simple and effective. At a fast pace, relatively cheap and high-density housing was constructed, all with very similar characteristics. This so-called “revolution-construction,” was the work of enterprising contractors who used catalogues with readymade ornaments rather than the design service of architects. The result was a visually coherent streetscape with classic tripartite brick façades, horizontal lines, vertical windows and stone ornaments. Whenever the original ground-floor dwelling had to be turned into a shop, the brick façade was simply cut away and replaced with a storefront.

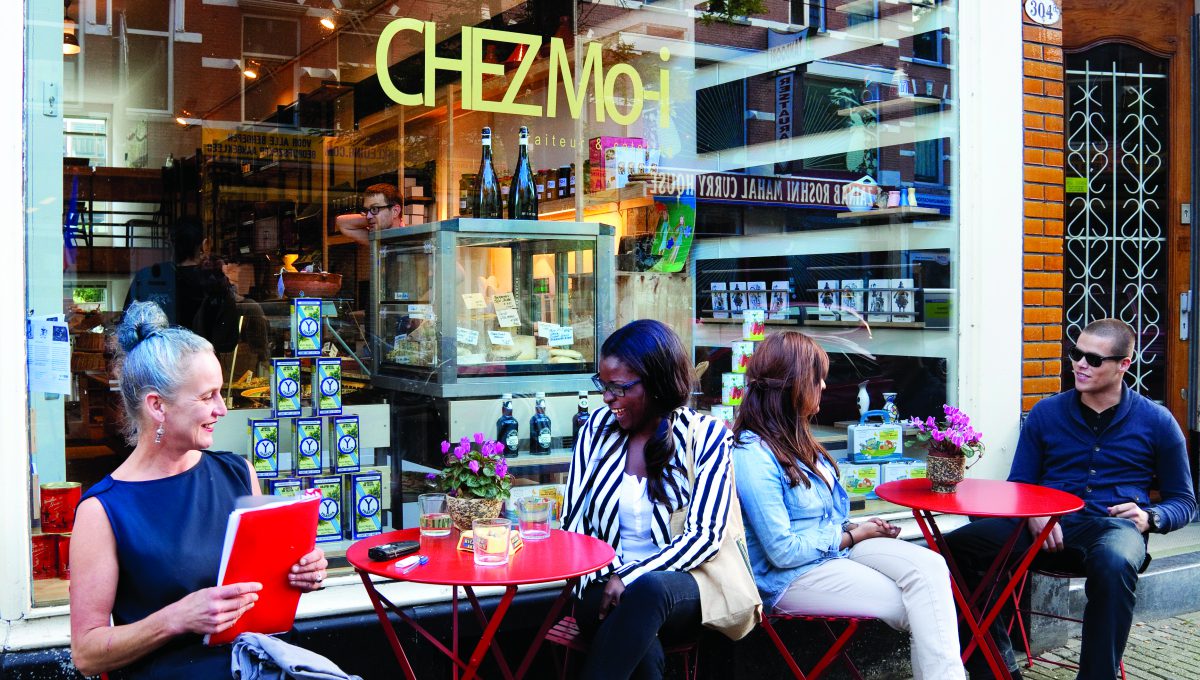

During World War II, when Rotterdam’s city centre was bombed, the Nieuwe Binnenweg took over the entertainment function of the city centre with shops, cafés, restaurants, and a cinema. During the fifties, sixties, and seventies the original city centre slowly reclaimed its central function. Since then, the Nieuwe Binnenweg has seen a decline of economic activities. Although marginal shops, vacant spaces, and poor maintenance of the houses and shops are evident, the Nieuwe Binnenweg has retained some of its beautiful icons such as high quality furniture stores and delicatessens.

©FFH Frank Hanswijk

©FFH Frank Hanswijk

©FFH Frank Hanswijk

©FFH Frank Hanswijk

Due to the economic decline of the street the local shopkeepers have since organised themselves and demanded action from the local government. In 2007, the local government and stakeholders of the Nieuwe Binnenweg started a program of revitalisation. The question was how to finance an integrated approach of revitalisation of the Nieuwe Binnenweg and how to involve the private owners in the program. To start the process, a wide range of stakeholders—major property owners on the street including the housing corporations and private property owners, the entrepreneur association, and the borough of Delfshaven—were invited to participate and formulate their goals and objectives. The revitalisation program was organized around four objectives: a safe and clean street; restoration of about 100 shops and houses; acquisition of about 40 new shops; and renewal and improvement of public space.

So with a wide support of social and business participants, the municipality created a political bind to direct and fund a large part of the revitalisation. The local public transport authority RET, responsible for the almost worn-out tram lines, and the European Fund for Regional Development (EFRD) financed most of the project. The local government offered partial funding for housing rehabilitation and economic development. All together, about €20 million public funding was generated and about €15 million of private funding through the building improvements. Entrepreneurs could also invest in their shop. They could obtain 55% of their investment with a max of € 15 000,- subsidy per shop.

© Hannah Anthonysz

© Hannah Anthonysz

The overall appearance of the street and façade consists of more than the plinths alone. Above eye level the brickwork enriched with tiling and baked enamel finish, mouldings and ornamental concrete finishing, contributes to the rich visual quality of the Nieuwe Binnenweg. One of the priorities in the program was to restore the visual quality the shops and houses. In over a hundred years these façades, and especially the storefronts, had suffered from poor maintenance and low-quality home-improvement. To preserve as much of the original quality as possible, the project focussed on the façade as a whole.

To restore the façades to their original historic quality, they were examined, following criteria from the City of Rotterdam’s ‘Commissie voor Welstand en Monumenten’ (Quality Assessment Committee). These criteria state, for example, that the transition from public to private space needs special attention, especially on a small scale. For example, entrance doors and doorbells should be of high quality. Doors should complement the architecture of the façade and original ornaments should be preserved. Storefronts should always be designed to match the original façade and should relate to the

adjacent architecture.

Although the situation was challenging, close observation of the storefronts demonstrated that not all had been lost; over the years, every new shop owner added a new layer to the storefront, avoiding the hassle of deconstructing the old one. Behind layers and layers of cheap cladding and billboards much of the old façades and ornaments were still there, and in great condition. Peeling off these layers exposed some remarkable findings, such as stained glass, tiled panels, and historic woodcarving. Brickwork was cleaned, bringing back the bright colours and layers of paint were stripped from mouldings and ornamental concrete to reveal its rich patterns and shapes. Much attention was given to apply the right colours for this 19th century architecture. These hidden treasures only had to be unveiled to restore the façades to their original quality.

Interested? Join The City At Eye Level and share your story!

Discover moreWith the entry of new specialty shops, the street is re-developing into an attractive city street. From this project and process the following lessons can be learned. First, it’s important for all participants to understand the significance of a long-term contract and realise that the process will take around eight years, or more. So all stakeholders should be committed to and understand the long-term contract. Second, to generate enough money the right stakeholders must be at the table, including the local businesses and social partners. Third, a written order for renovating the buildings with a specific attention for the original quality is a good instrument to get private owners involved, but a subsidy-instrument is necessary to work with them on integral improvement plans. Finally, it’s difficult to stop a 20-year process of decline in only four years. In eight or ten years from now, we will see how the Nieuwe Binnenweg has developed.